The Glamour of the 1960s Big Carrier Royal Navy

It takes a while coming, but when, finally, the warship is spotted cruising across the Mediterranean – through the cabin window of a Wessex helicopter of the Fleet Air Arm, no less – KGB agent Ilya Kuryakin (Armie Hammer) enquires what on earth it is.

With the crisp and dry sarcasm only the head of British naval intelligence could deliver, Commander Waverly (Hugh Grant) explains: ‘It is an aircraft carrier Kuryakin – for a special agent you are not having a very special day.’

British aircraft carrier HMS Hermes on sea trials, a type of ship featured in ‘The Man from U.N.C.L.E.’

She would be the last of the RN’s big deck aircraft carriers of the 1960s. Photo: Strathdee Collection.

It is indeed a flat top, and a British one rather than a Yank variant (as is usually the case in movies). From its appearance, as the Wessex approaches for a landing, the ship in question is Victorious or Hermes.

She has a flight-deck bursting with other helicopters and, most wonderful of all, nifty little Seahawk fighter jets. That for once the Royal Navy gets the glory in a Hollywood movie, is only sensible (and accurate). For a taster (including naval elements) watch this extended trailer:

At the time ‘The Man from U.N.C.L.E.’ is set – around 1964 – the British fleet still ruled the Mediterranean and, in fact, routinely deployed several big deck aircraft carriers all the way from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean.

Of course back in the mid-1960s the Soviet Navy did not have an aircraft carrier at all, so perhaps it is understandable that the sight of such a vessel might flummox a KGB agent.

Having spent a fair bit of time writing about the wielding of UK and US Navy carrier power and the rise of Soviet maritime power (including carriers by the late 1960s) I was thrilled to see proper, authentic hardware depicted in this movie. It really did capture the essence of certain other aspects of the Cold War era (not just the fashion either but also espionage and the whole East-West rivalry thing) as touched upon in my own Hunter Killers’.

Movie director Guy Ritchie has a real eye for naval detail and, as someone in his late forties, no doubt recalls the fantastic 1970s BBC TV documentary ‘Sailor’ about the big deck carrier HMS Ark Royal. For many of us born in the 1960s that show was incredibly exciting, as was the original ‘Man from U.N.C.L.E.’ television series. Both were very, very cool.

Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s the big deck carriers of the Royal Navy – and the dizzying succession of strange and fantastic fighter jets that flew from them – were the epitome of a Britain that, despite all its woes, still burned with the white heat of technology. It aspired to be up there with the naval big boys because it could and should.

Anyway, Ritchie’s movie only reflects the reality that there were two main players out there doing business in the fight against the Soviets during the Cold War (especially in the realms of intelligence and naval forces), namely the UK and USA.

In ‘The Man From U.N.C.L.E.’, a stylish, sexy romp that takes us from East Berlin to Italy and out into the Med, the Russians and Americans – and eventually the British – unite against fiendish neo-Nazis seeking a nuclear weapon.

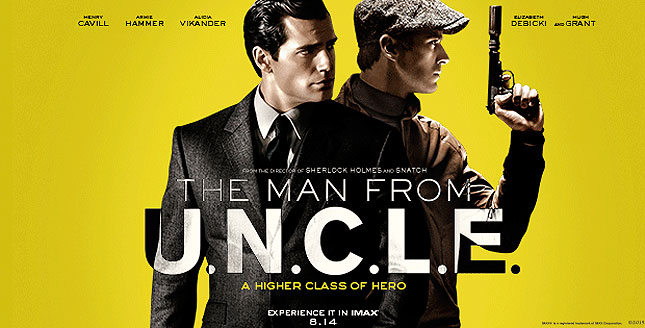

Art work from the new movie, ‘The Man from U.N.C.L.E.’ (Warner Bros).

The climax of ‘The Man from U.N.C.L. E.’ movie features a Royal Marine (or SBS) raid under cover of darkness with Kuryakin and CIA operative Napoleon Solo (Henry Cavill, a Brit using an American accent) along for the ride. The Royal Navy later delivers the coup de grace of the whole drama.

Both Hammer and Cavill live up to the roles originated by Robert Vaughn (Solo) and David McCallum (Kuryakin) while in today’s ‘U.N.C.L.E.’ Alicia Vikander (Gaby) is a welcome addition to the team. Grant’s Waverly is among his better performances of late.

I had afternoon tea with the original Kuryakin once and he was a very charming chap. I must confess I was especially eager to talk about his other famous role, in ‘The Great Escape’ movie, in which he played a Fleet Air Arm aviator on the run from the Nazis, but thereby hangs another tale.

The only jarring note of the new movie is a so-called Nazi submarine that is clearly an Oberon Class (British design) boat. Bearing in mind that it is CGI creation it is a puzzle they could not create a U-boat, as there were plenty of former Nazi submarines still in commission during the 1960s. That’s a trivial moan more than made up for by the unusually prominent and accurate portrayal of the 1960s Royal Navy, which looks dynamic and decisive.

Commander Ian Fleming, who, in addition to creating naval superspy James Bond had a part in originating ‘The Man from U.N.C.L.E.’ for TV, would be most gratified.

• This is a variant of an article is to be published in the October 2015 edition of WARSHIPS International Fleet Review magazine, available from September 18.

‘The Man from U.N.C.L.E.’ (Warner Bros, Cert 12A) can still be seen at the cinemas and will be released on DVD and Blu Ray in the near future.

Iain Ballantyne’s next book, ‘The Deadly Trade: A History of Submarine Warfare’ is currently being worked on most diligently, and is due for publishing by Orion Books in 2017.