The strange tale of the Balaclava Beluga

(and a new Russian stealth submarine that will operate from the Crimea)

The current turmoil in the Crimea and television news reports from Balaclava reminded me of a trip I made to that part of the world in the dying days of the Soviet Union. Thereby hangs a tale and I thought it worth dusting off, especially as it was an episode that didn’t make it into my new book ‘Hunter Killers’ and deserves not to go ignored. It also appears my encounter with a secret Russian submarine was merely the prequel for a lethal new vessel that will soon be operating from the Crimea (providing another reason why Moscow will never give up Sevastopol).

Elderly men wearing flat caps and clad in frayed polyster zip up jackets queued patiently alongside babushkas swaddled against the cold, empty shopping bags dangling forlornly from their gnarled fingers. Quite what they were waiting to receive from the ramshackle shop was not clear: Potatoes? Tea? Shoes? In the Soviet Union people waited in line for whatever they could get no matter how paltry it was.

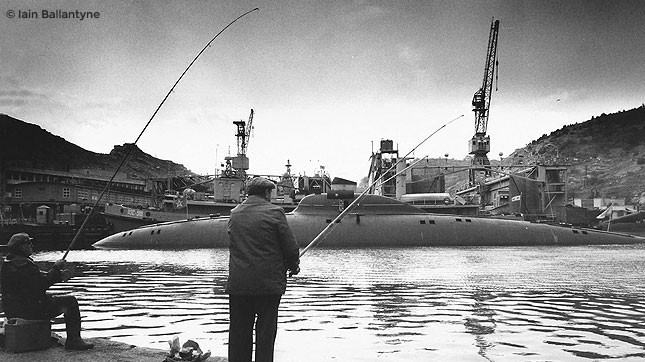

Not far away, an enterprising set of fellows showed similarly heroic (and equally vain) patience, fishing rods poised over the black, gently rippling waters of Balaclava Harbour. They were not likely to hook decent-sized fish in there, more inclined to pull out an old boot.

Shot taken at Balaclava Harbour in the Crimea, late 1991, showing never before seen Russian submarine, called the Beluga. Photo: Iain Ballantyne.

The anglers stared miserably into the distance, not seeming to understand that the biggest intelligence catch for many years was actually moored next to a floating dock just a few yards away.

I raised my camera to capture the scene – in the foreground moribund, miserable fishermen and there, almost on the ends of their lines, a sleek, shark-shaped submarine of a kind never seen before by Western eyes.

Rather than being arrested by KGB shadowers, with my camera smashed into pieces, I got away with snapping off several dozen frames. I was part of an official group being shown around Balaclava as a guest of the Russian Navy, so I seemed to have immunity to strong-arm tactics. (As I would find out just under a year later, in another part of Russia, armed KGB agents in those days invariably followed Western VIPs around – to protect them from thugs – and were not afraid to loose off a few shots in the air to safeguard special visitors – but that’s a story for another day.)

View across Balaclava in late 1991, with a solitary elderly Juliett Class diesel-electric cruise missile submarine alongside the Soviet Navy submarine base. Photo: Iain Ballantyne.

In Balaclava, a jolly, rather rotund Russian admiral held forth with a booming voice about the harbour – which of course for Britons, as he acknowledged, held great significance. During the Crimean War of the 1850s it had been a major portal of invasion for Queen Victoria’s army. We had just been over to the Valley of Death – now covered in vineyards rather than the corpses of slain cavalrymen – and this was the latest stop on the British diplomatic group’s tour. As a journalist I was a hanger-on, listening and watching from the sidelines.

In late 1991, with the Soviet Union breaking up rapidly – and only a matter of weeks until it was dissolved – the issue dominating the headlines was: What will happen to the nuclear weapons currently residing in the various breakaway bits? The Ukraine in particular was home to many nukes and also a massive Russian Navy presence in the Crimean Peninsula. Yet it seemed amid all the fuss over the warheads somebody had forgotten to hide this submarine at Balaclava away from prying eyes. They could easily have slid it out of sight for, unknown to us at the time, the cliffs at Balaclava concealed cavernous submarine pens – like some Bond villain’s lair for real – but on the day of our visit an order to conceal the submarine failed to come down the chain of command.

Back in the UK, not really understanding quite how much of a scoop the pictures I had taken were, I did some investigating. It turned out the Balaclava submarine was a revolutionary kind of craft called a Beluga. It was an experimental prototype, created to see if the stealthy shape of a nuclear-powered attack submarine could be combined with a new type of propulsion more silent than reactor machinery, called closed-cycle diesel.

Suddenly we were in the realms of Tom Clancy’s ‘The Hunt for Red October’ and my humble regional evening newspaper had a world scoop – but I wasn’t the only one taking pictures. There were others there too. Could we beat them to the punch? My paper ran the story big and bold; a front-page lead ‘World Exclusive’ on the ‘Secret Red Sub’, with an inside page carrying more detail and a sidebar on the recent Hollywood blockbuster version of ‘Hunt for Red October’. It explained that the movie featured a fictional submarine with revolutionary propulsion, just like the Beluga (well, not quite, but similar enough).

As for the much-vaunted Beluga, it seemed to be a bit of a dead end, being decommissioned after several years of trials. The Russian Navy struggled to keep even its older, less cutting edge submarines at sea so there was no point back then in carrying on with trying to develop radical new types.

Today the closed-cycle Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) submarine proliferates across the world, thanks mainly to the Germans, who don’t mind supplying them to whoever has the cash (and a need for patrol submarines almost as deadly, in certain waters, as the nuclear-powered attack boats). The Germans have always been on the cutting edge of submarine technology. One of James Bond creator Ian Fleming’s prime objectives when working for Naval Intelligence at the close of the Second World War was to ensure the British seized German submarines before the Soviets got them, especially high-speed craft with closed-cycle AIP propulsion. The British succeeded but were later forced to share them with the Americans and the Russians, with all three nations basing their early Cold War submarines on the seized Nazi U-boats. Read ‘Hunter Killers’ for more on all that.

An advanced Lada Class diesel-electric submarine constructed by the Admiralty Yard in St. Petersburg, which is also building similar (but even more capable) Varshavyanka Class boats. Photo: Admiralty Shipyards JSC.

In naval technology (and fiction) everything, so it seems, is cyclical. In Ian Fleming’s novel Moonraker (first published in 1955) the climactic sequence features a super-fast Russian submarine that can do 25 knots under the water. The former British naval intelligence officer was there before Clancy – merging fact with fiction.

As for the Balaclava, judging by the news broadcasts, it has changed somewhat in the 23 years since I was there, with what looks like swanky apartments on the cliffs. One thing I did gain an appreciation of during my visit to the Crimea was how deeply embedded Sevastopol and the rest of the peninsula is within the Russian psyche. The Russians shed blood to keep it not only during the Crimean War but also during bitter fighting in the Second World War. Allowing the Ukraine to even nominally keep the Crimea – which was Russian territory until 1954 – and especially after the break-up of the Soviet Union in the 1990s really aggravated the Russians. Well, now they have taken it back though it is hard luck on Ukrainians who live there. It is a story that will run and run, for they don’t want to yield the Crimea either.

With President Putin’s interest in building up the Russian Navy again and exerting his country’s hard power presence in world affairs there are said to be new submarines on their way to operate out of the Crimea.

Another view of the Lada Class, precursor to the Novorossisk and her Varshavyanka Class sister vessels, which are destined to operate out of the Crimea. Photo: Admiralty Shipyards JSC.

Last November at the Admiralty Shipyard in St. Petersburg, a new kind of diesel-electric submarine called the Novorossisk was floated out, with sister vessels soon to follow. Up to ten of the new Varshavyanka Class boats (said to be super stealthy and with exceptional underwater endurance for a conventional type) are reportedly on their way. They may operate from Novorossisk itself, on the eastern shores of the Black Sea. It is today Russia’s primary oil exporting port and a burgeoning naval base. However, you can bet some of the new submarines will be based at Sevastopol. Their primary targets, as part of a new task force that will aim to also operate in the eastern Mediterranean, are four Med-based American guided-missile destroyers destined to provide Europe with a ballistic missile defence shield.

Novorossisk and her sisters – no doubt incorporating technological advances pioneered in the Balaclava Beluga all those years ago – will sally forth from their Crimean base to shadow those American vessels. And that’s a major reason the Russians will not give up the Crimea. It is not only part of their soul but also strategically of vital importance in Putin’s grand venture to establish a new world order (in which Russia again challenges Western hegemony).