Is the way forward for the UK’s hard-pressed Submarine Service a case of going back to the future and buying in German technology?

In 1910, the intrepid Captain Roger Keyes, who had as a young naval officer participated in operations against slave traders off east Africa and helped quell the notorious Boxer Rebellion in China, found himself in command of the Submarine Service of the Royal Navy.

A surface fleet outsider with no specific technical skills or even sea-going experience related to submarines, Keyes nonetheless delegated well. He also quickly assessed that development of Britain’s submarines was being hampered by the monopoly that Vickers held over construction of the vessels and provision of their equipment, including periscopes and engines.

Keyes went overseas for better periscopes and diesel engines and even bought in French and Italian submarine designs. The off-the-shelf engines and designs were not necessarily a success. The procurement of French and German retractable periscopes – soon copied and improved on by British firms – represented a huge step forward. Rather than a fixed scope on the outside of the hull – elevated via a knuckle pivot, with the submarine porpoising to poke it above the waves or withdraw it – the new style periscope could be extended and retracted mechanically from inside the submarine (which could keep a steady depth). Keyes’ efforts were not the first, nor would they be the last instances of the British fleet copying and improving on German technology.

An early A Class submarine of the Royal Navy, which did not have a German or French origin retractable periscope at the time (1903). Photo: Used by kind permission of BAE Systems.

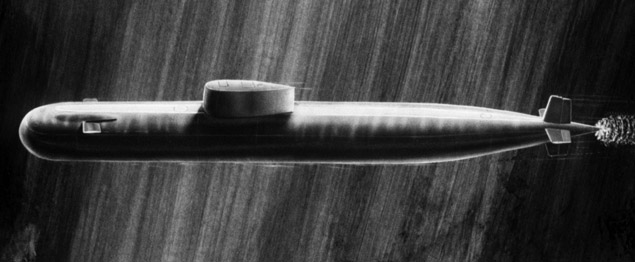

The three prime protagonists in the undersea contest at the core of the Cold War – the USA, Russia and Britain – all based their 1950s and 1960s diesel-electric patrol submarines on advanced technology U-boats produced for the Nazi regime during WW2.

The Royal Navy also had to move into nuclear-powered submarines to stand a chance of competing, even in a minor way, with the immense efforts of the Soviet Union. Ironically, the massive nuclear submarine fleet Moscow built played a key role in bankrupting the USSR and handing victory to the West.

Today nuclear-powered submarines are more expensive and complex than ever – a bigger challenge than the Space Shuttle to manufacture – with the Royal Navy’s new Astute Class attack submarines costing between £1.6 billion and £747million each (they get cheaper the more you build). The latest comparable Russian vessels cost well in excess of that.

As a consequence, any nation without deep pockets (or a willingness to bypass state provision of Social Welfare and universal healthcare) finds it really hard to afford more than a few nuclear-powered submarines, if any.

In an age of economic austerity, with the UK’s Conservative government beginning its new term of office with an instant £500 million sliced off the defence budget, can the UK afford to stay in the business of nuclear-powered submarines? Does building just seven Astutes offer value for money in terms of global presence and operational capability?

There have been claims the Astutes are too slow to keep up with the new aircraft carriers they are meant to protect and have suffered from other technical problems, though the Navy insists the teething problems are being ironed out.

The Royal Navy nuclear-powered submarine HMS Astute arrives at Naval Station Norfolk in the USA for combat exercises against an American attack boat. Photo: Todd A. Schaffer/US Navy.

At the moment – with the older generation Trafalgar Class submarines based at Devonport being decommissioned and the Astutes slow to come on line – the UK is lucky if it can get two attack submarines on deployment.

Yet there are a wide variety of jobs for British submarines to do around the world, including intelligence gathering, protecting the UK’s Trident submarines and hunting other vessels. Last year, at the Undersea Defence Technology (UDT 2014) conference in Liverpool, the current head of the Submarine Service, Rear Admiral Matt Parr, suggested modern navies are perhaps pushing their people too far and destroying their quality of life. It is no secret that fewer British boats are spending more (and longer) periods away from home and it is placing a huge strain on the home lives of the submariners.

Rear Admiral Parr, who in the 1990s commanded a Devonport-based submarine and is a former deputy boss of Plymouth-based Flag Officer Sea Training (FOST), last week told the UDT 2015 conference in Rotterdam there is increased demand for Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) and Special Forces operations. Rear Admiral Parr revealed the Prime Minister himself decides the nature of modern British submarine operations.

Even so, there is a feeling that the current government is afflicted with incoherence in foreign and defence policy and it doesn’t really know what the Navy is for (or it wouldn’t cut defence spending, drive down warship numbers and make highly skilled sailors redundant).

With the strain on submariners and the mission portfolio for the smaller numbers of vessels as broad as ever, is it time for a revolutionary idea to be considered? Is it time to buy German again?

Having gone all-nuclear in the early 1990s, by abandoning diesel-electric ‘conventional’ submarines, might Britain be better off ditching the nukes and going back to the cheaper, greener and much-easier-to-build diesels?

Should it buy lots of U-boats? The Germans make excellent submarines that offer capabilities undreamed off during the Cold War. Their Type 212A U-boats are cutting edge and proven – quieter than a nuclear-powered submarine, small enough to more easily carry out Special Forces operations in shallow waters and with powerful submarine-detecting sonar. Their weapons load is impressive, though it does not currently include cruise missiles or Anti-Shipping Missiles (ASM).

The new Type 212 U-boat U35 undergoing tests and trials. Photo: Björn Wilke/German Navy.

The Type 212 German submarine U32 surfacing. Photo: Björn Wilke/German Navy.

The Type 212A’s Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) means it can stay submerged (and hidden) for up to three weeks. It is capable of crossing the Atlantic without once surfacing, or even using its snorkel system, to take in fresh air and expel fumes. The Achilles Heel of previous generation conventional submarines was potential exposure to an enemy when expelling fumes or sucking in fresh air.

Each Type 212A costs 370 Euros (£260 million, around a third of the cost of a single Astute). If even bankrupt Greece can build a variant of the most modern U-boat (the Type 214 export version), could the Type 212A not be built at Devonport, the UK’s primary submarine refit yard? Babcock does still construct small surface warships, although at Appledore rather than in Plymouth, so why not conventional submarines? Submariners with long and deep experience of submarine operations will tell you that if the UK wants to remain a serious global player it does need the sheer power, huge endurance and reach of nuclear-powered attack submarines.

They are many times more capable and better armed than any diesel, the battleships of today. Why not save the Astutes for the long-range missions and use the U-boats closer to home and for specialist missions such as landing Special Forces?

That way submariners could be rotated through a less gruelling work routine and Britain would have the force levels necessary to counter the rising Russian threat and handle a lot more besides. This would include the job of training warships receiving ASW training with FOST, a task currently undertaken by the diesels of the German and Dutch navies. The new British U-boats could even be based at Devonport. It will have empty submarine berths once the last Trafalgar Class submarine has been decommissioned in 2022.

For more news and analysis of modern naval issues see WARSHIPS International Fleet Review . In addition to being the founding and current editor of WARSHIPS IFR, Iain Ballantyne is the author of the true-life thriller ‘Hunter Killers’ (Orion), which tells the dramatic story of British submarines and submariners in the Cold War, including how the two sides in that long confrontation developed submarines from WW2 German technology.

An edited version of this article was published a commentary in the Western Morning News on June 15.