Submarine Warspite

The hunter-killer that took on the Soviets

and pushed back the boundaries of undersea warfare

The eighth British war vessel named HMS Warspite was born during an arms race similar to the one that created her immediate predecessor at the beginning of the 20th Century. This time, however, it was about building nuclear submarines rather than dreadnoughts.

Despite the UK entering the Cold War construction race late – and capable of only building and operating small numbers compared to the Russians and Americans – the quality of British nuclear-powered attack boats (known in the Royal Navy as Fleet submarines, or hunter-killers) was high, including the new HMS Warspite.

Like the Queen Elizabeth Class battleships, submarine Warspite and her sisters of the Valiant Class were examples of cutting edge British naval architecture. The first British nuclear submarine had been the one-off HMS Dreadnought, completed in April 1963, around eight months before Warspite was laid down and a new HMS Valiant was launched.

With a displacement of 4,500 tons and length of 285 feet, submarine Warspite (also known as a Ship Submersible Nuclear, or SSN) had six 21-inch torpedo tubes and was powered by a British-made pressurised water-cooled nuclear reactor. Hitting the water on 25 September 1965 at the Vickers submarine yard in Barrow-in-Furness, Warspite was commissioned on April 18, 1967. Her Commanding Officer, Commander R. R. Squires, observed at the time: ‘With her high speed, long endurance and sophisticated weapons system, she is a ship thoroughly worthy of an illustrious name in this modern age.’

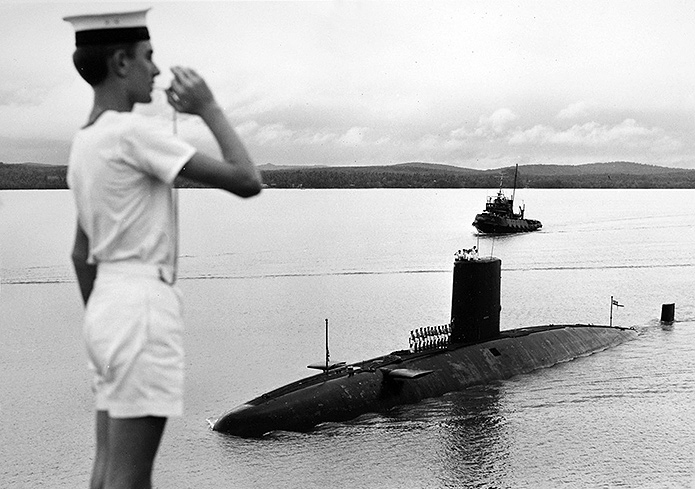

Indian Ocean, February 1968: HMS Warspite follows strike carrier HMS Eagle and her escorts, as a Wasp helicopter keeps an eye on the SSN. Photo: Royal Navy.

Like the battleship of 1913, submarine Warspite contained many innovations including being the first British naval vessel to rely entirely on gyroscopes for navigation rather than a magnetic compass. Also, because of her nuclear power, submarine Warspite could stay submerged for weeks without coming up for air, a feat made possible by air conditioning, purification systems and electrolytic gills.

In 1967/68 Warspite’s first deployment took her to the Far East, recording the longest submerged run then achieved by a Royal Navy submarine – 6,000 miles dived. Aside from boosting the prestige of the Submarine Service and gaining good publicity, such voyages had an operational relevance. They helped test the technological and human boundaries so that, in a time of hot war, the boats could, hopefully, deploy for many weeks at a time, remaining hidden and ready to strike.

HMS Warspite leaving Singapore, January 1968 after her record-breaking submerged transit to the Far East naval base. Photo: Royal Navy

Submarine Warspite returned to her home base at Faslane on the Clyde in March 1968 and that September for the first time visited Plymouth – where super dreadnought Warspite had been launched 55 years earlier. There was great interest not only from the local press but also from the families of the crew who visited the Devon naval base for a tour of the boat.

The visitors were keen to gain an insight into the secret world of the Cold War UK submarine force. They learned that Fleet submarines flew under water, at speeds of more than thirty knots and, because there was no room for error, Warspite was always run at war pitch. Procedures for every eventuality imaginable were rehearsed endlessly. Fire, flooding, loss of reactor and/or hydroplanes were the chief disasters the crew of submarine Warspite hoped never to encounter. Added to them were the stresses and strains of jousting with the Russians under the sea and just seven months after the Plymouth visit Warspite nearly came to grief in the Barents Sea.

At the time British submariners were working very hard to counter Moscow’s rising maritime strength. The Americans might have more submarines, but no fleet was more adept at penetrating the Soviets’ backyard than Britain’s. By then the Royal Navy had two so-called ‘Special Fit’ nuclear-powered submarines – Valiant and Warspite – and they would be required to go into the High North time after time.

Warspite had received her Special Fit capabilities at Chatham Dockyard in Kent, where nuclear submarine refits were at that time carried out. It made her supremely suitable for operations up North. She could now pursue four types of intelligence: ACINT (Acoustic Intelligence); COMINT (Communications Intelligence); SIGINT (Signals Intelligence) and ELINT (Electronic Intelligence). Special Fit equipment – much of it operated by the specially trained sea riders – was not given to every submarine and it placed Warspite on the cutting edge of Cold War espionage.

Tim Hale, who was in 1968 submarine Warspite’s Executive Officer, or XO, has revealed that on patrols in seas bordering Russia, the submarine was there to ‘watch the Soviet Navy through the periscope doing their manoeuvres.’ He added: ‘We listened to them talking to one another, quite often in uncoded, clear language. We recorded their signals, their messages, and tried to figure out what they meant. We recorded their missile firings and their torpedo firings and what they said during them.’

In October 1968, while on her first foray into Northern waters HMS Warspite was involved in a collision, which to this day the UK Ministry of Defence maintains involved an iceberg. Other accounts, including the inside perspective on the incident – first published in ‘Hunter Killers’ – maintain it was an Echo II guided-missile submarine of the Soviet Navy that Warspite encountered rather than a big jagged lump of ice.

The reality was, that as the British submarine turned to port under the stern of the Russian boat she made physical contact. Her fin scraped along the underside of the Echo II. Aboard the Soviet submarine, sailors were wide-eyed with alarm as the deck tilted dramatically to starboard. Their vessel vibrated violently, shuddering to the force of the collision. Her screws chewed Warspite’s fin, blades slicing into its thin skin.

While Warspite was pushed down and over to an alarming degree, she did not crash to the floor of the Barents Sea, for her CO, Cdr John Hervey, ordered her surfaced immediately while her reactor was kept on line by the boat’s quick-thinking marine engineer officer. The submarines broke the surface close to each other but cool heads prevailed on both sides. After an inspection of the damage suffered by the British boat – finding Warspite’s fin chewed and very severely crumpled and other significant scars – the SSN limped back to the UK.

A starboard view of a Soviet Navy Echo II Class guided-missile submarine underway on the surface, the same type as the alleged ‘iceberg’ Warspite was in collision with in the Barents Sea in late 1968. Photo: US DoD.

With the Russian presence in the Mediterranean growing, it was inevitable the repaired Warspite would sail the same waters her battleship forbear had mastered as Admiral Cunningham’s flagship. This time HMS Warspite was not countering an Italian battle fleet wielded hesitantly, but rather staying hidden under the sea to monitor a determined and sustained show of force by the Soviets.

By the summer of 1971, after her deployments to the Mediterranean, Warspite was back at Chatham for a refit that included refuelling her reactor. Recommissioned more than two years later, she subsequently deployed to the Far East in September 1975, returning home the following June.

The submarine suffered a serious diesel generator fire while alongside at Liverpool and was out of action for more than a year. After extensive repairs she went back to the Cold War frontline in 1978 and then entered a refit at Chatham in 1979. Three years later, as the Falklands War blew up, Warspite was finally coming to the end of that major work package.

The refit had made Warspite a virtually new submarine and was therefore the equivalent of the battleship’s 1934-37 rebuild. The SSN’s old reactor core had been replaced as were weapons systems and sensors. Also included was installation of Sub Harpoon, a highly capable anti-shipping missile, with Warspite one of the first British boats to receive it.

It was a handy weapon to use against the Argentinean navy, so Warspite’s CO, Commander Jonathan Cooke, was told to get his boat out of refit and into action as soon as possible. ‘We got the red alert to go to war,’ he recalled. ‘Rather than have six months post-refit work up, we compressed everything into four weeks.’ Once Warspite arrived in the South Atlantic she secured an uneasy peace by prowling in waters around the Falklands and lurking off the coast of Argentina.

Warspite’s deployment ended up being a remarkable record-breaking patrol of 112 days, 88 of them submerged. At the time it was a fortnight longer than any other British submarine had achieved. When she returned to Faslane Warspite sported model penguins on her outer casing (to signify the South Atlantic aspect of her patrol) and it was disclosed her food had almost run out.

During the 1980s the East-West face-off continued unabated but, with the fall of the Berlin Wall and beginning of the Soviet Union’s fragmentation, it was clear the Cold War had ended in victory for the West. The Royal Navy faced so-called ‘peace dividend’ cutbacks in 1990-91, which included Warspite being retired from service mid-way through a refit at Devonport Dockyard.

And that is where the SSN remains, discarded like her illustrious immediate predecessor in the wake of a war (even though she never fired her weapons in anger, unlike the battleship, whose guns were hot so often). The hulk of submarine Warspite is mothballed and tied up alongside other Cold War SSNs, including HMS Conqueror, which sank the Belgrano during the Falklands conflict. Such relics have not yet been scrapped because of their residual radioactivity and the tricky problem of disposal is yet to be solved.

• This blog draws on material in both ‘Warspite’ (Pen & Sword, 2010) and ‘Hunter Killers’ (Orion Books, 2013).

Top image: Warspite flying her very long paying off pennant as she sails past Plymouth Hoe for the last time on her way to decommission at Devonport Naval Base in the early 1990s. Photo: Babcock.

For more of the inside story of SSN Warspite’s exploits at sea, including the drama of her crunch with the Soviet submarine, see ‘Hunter Killers’

The epic span of submarine warfare through the ages, including during the Cold War, is chronicled in ‘The Deadly Trade’

The story of all British warships named HMS Warspite is told in ‘Warspite’ including the submarine, but it is, above all, the story of the legendary battleship of WW1 and WW2.