An Amazing Fighting Life – Part 1

An Amazing Fighting Life – Part One

From Jutland Hero to Desperate Hours in WW2

To further Mark the 100th anniversary of HMS Warspite’s launch, we chart the legendary battleship’s incredible career through two world wars. Iain Ballantyne bases this account on edited extracts from his book ‘Warspite’.

In late 1915, having been commissioned into the Navy, Warspite joined the 5th Battle Squadron – which had just been created for the Queen Elizabeth Class vessels. It consisted of HMS Barham (squadron flagship), HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Warspite. The remaining sister vessels – HMS Malaya and HMS Valiant – would join the following year.

In May 1916, the 5th BS was sent to reinforce the Battle Cruiser Fleet (BCF) based at Rosyth. The Squadron and the BCF deployed from the Firth of Forth on the evening of May 30 and the next afternoon would engage the vanguard of the High Sea Fleet, Germany’s foremost naval striking force.

It was a fight that saw the battlecruisers heavily battered – with HMS Indefatigable and HMS Queen Mary destroyed and few survivors from their crews. The four Queen Elizabeths of the 5th BS – the lead ship of the class was in refit following a detachment to take part in the Dardanelles campaign – saved the day.

Steaming into action, they gave the German battlecruisers a pounding in return, but when the entire High Sea Fleet crested over the horizon had to withdraw. There followed an epic running fight during which, at one stage, Warspite held off the enemy battle fleet.

Warspite’s junior medical officer, Surgeon Lieutenant Gordon Ellis would later remark: ‘Fighting the entire German navy with six battlecruisers and four of us (even if we were the 5th BS) seemed rather long odds, and we hoped exceedingly that Jellicoe’s appearance would not be long delayed.’

Fortunately for Warspite the German ships broke contact. They were forced to turn away by the Grand Fleet – commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe – finally entering the battle. It brought substantial weight of fire to play, unleashing a vast arc of death. The British fleet could focus its full firepower against the Germans but the latter were in line astern and could only bring a small proportion of their guns to bear.

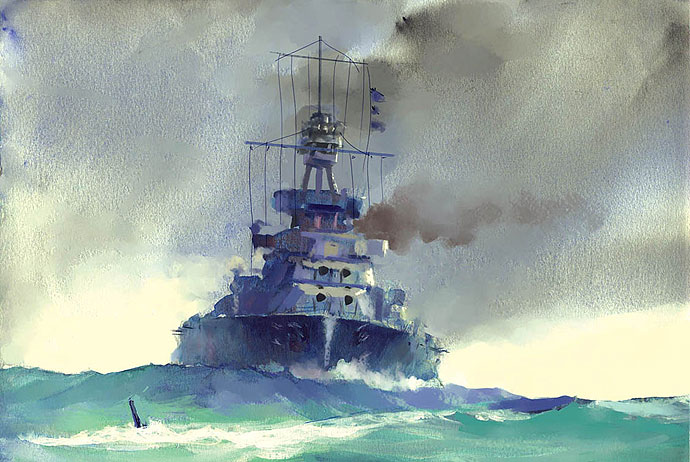

Badly damaged during the Battle of Jutland, HMS Warspite is attacked by U-boats off the Scottish coast but here tries to ram one of them (see periscope bottom left of image). Illustration by Dennis Andrews.

Having suffered two-dozen heavy shell hits, Warspite was ordered to head home, but on the way faced the new danger of predatory U-boats lying in wait off the coast of Scotland.

Going on deck to get some fresh air, Surgeon Lt Ellis found this scene: ‘Only a few hours before Warspite had been one of the cleanest and smartest looking ships in the fleet, her decks spotlessly white, and her light grey paint, freshly put on only recently, gleaming everywhere in the sunshine. Now her decks were filthy, littered with debris and in places torn up by shells. One of the quarterdeck ladders had been blown away, her funnels had ragged holes in them, the small iron ladder on X turret had been bent and twisted and broken away from its lower supports, whilst the side of the turret was covered with marks from a glancing hit.’

Somehow the Warspite, despite being attacked more than once by U-boats, managed to escape further damage and entered dock at Rosyth for major repairs. Fourteen of her men were dead and 18 wounded, but she had been very lucky not to be sunk as the 150 holes in the battleship attested.

WHEN the post-WW1 defence cuts axe fell in the 1920s the Queen Elizabeth Class ships were retained and Warspite was remodelled twice. The work she received in the late 1930s, as new war clouds gathered over Europe, was almost a complete rebuild.

A radically reconstructed and modernised HMS Warspite departs Portsmouth in the late 1930s to become flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet. Strathdee Collection image.

The opening months of WW2 were quiet in the Mediterranean, where Warspite had been assigned to become flagship of the formidable Vice Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham. The battleship was, though, temporarily detached for duties in the Atlantic and it was while in Arctic waters that she found fresh fame.

In April 1940 the Germans invaded Norway, and sent a powerful destroyer force to Narvik. It was the scene of a fierce battle with British destroyers in which the Royal Navy fought valiantly but came off worse. The British decided to strike the ten German destroyers lurking at Narvik with overwhelming force. A hunting pack of nine British destroyers was assembled around Warspite.

The night of April 12/13 was bitterly cold, with an uncomfortable swell and ice coating the battleship’s decks. Deep inside her hull the fuses of Warspite’s 15-inch shells were altered to non-delay. The sheer weight of the one-ton shells meant they would cut through the thin skins of German destroyers like a hot knife through butter. If they weren’t set to explode instantly on contact, they might go off after coming out the other side.

At 5.00am on April 13, Warspite started her journey up the fjords to Narvik, with three destroyers steaming ahead of her using minesweeping gear to clear the way. Others were posted evenly around her, all of them straining at the leash to have a crack at the enemy. With oppressive clouds pressing tightly down and snow flurries swirling off the steep sides of the fjords, visibility was around ten miles at best.

Sending a battleship into such confined waters was a real gamble, particularly with an unknown number of German submarines operating around Norway. As the battleship gathered pace a U-boat, which had been carefully stalking Warspite collided with a rock and was temporarily exposed. HMS Eskimo chased the submarine off with a shower of depth charges.

A Swordfish floatplane from Warspite was launched to scout ahead and soon reported two enemy destroyers not far away. They greeted the plane with a storm of anti-aircraft fire but failed to score any hits. Skimming over Narvik, the Swordfish sighted another German destroyer in harbour and then flew up the Herjangsfiord to the north. It found U-64 just moving away from a jetty at the small settlement of Bjerkvik.

Warspite was a lucky ship, here illustrated by a U-boat running aground in a rocky Norwegian fjord in April 1940, just as the submarine is about to launch torpedoes at the battleship. Illustration by Dennis Andrews.

The Swordfish dived on the U-boat to release bombs, the German submarine replying with fire from a 37mm anti-aircraft gun. One of the bombs hit the base of the conning tower, making short work of the submarine. She sank by the bows in less than 30 seconds, drowning a dozen of her crew. This was the first U-boat to be sunk by a British naval aircraft in WW2.

Meanwhile, a furious close quarters fight had developed elsewhere in which the German destroyers were one by one sunk, or forced to run themselves aground.

Warspite’s 15-inch guns on occasion achieved devastating effect as the narrow fjord trembled to their roar. It was a resounding victory for the Royal Navy in an otherwise dismal campaign.

RETURNING to the Mediterranean, Warspite welcomed Admiral Cunningham and his staff back. The guns that helped to wipe out most of the German Navy’s destroyer force soon managed to make the entire Italian fleet retreat, with one devastating hit on the Italian flagship at the Battle of Calabria in early July 1940.

Warspite opened fire on the leading vessel – the flagship Giulio Cesare – from a distance of more than 23,000 yards. Even though it was only a single hit amidships it won the battle. Admiral Cunningham would later write of this moment: ‘The Warspite’s shooting was consistently good. I had been watching the great splashes of our 15-inch salvos straddling the target when, at 4pm, I saw the great orange-coloured flash of a heavy explosion at the base of the enemy flagship’s funnels. It was followed by an upheaval of smoke, and I knew that she had been heavily hit at the prodigious range of 13 miles.’

More glory followed in March 1941 during the night action off Cape Matapan, where Warspite led sister ships Valiant and Barham, plus escorting destroyers. Pursuing the main Italian battle fleet, the British instead found luckless enemy cruisers. The Italian warships straying into the killing zone were two Zara Class heavy cruisers, the Fiume and Zara (10,000 tons displacement and carrying 8-inch guns) together with a destroyer escort.

They had been sent back to assist a sister ship – the Pola – which had been stopped dead in the water after being hit by a British airborne torpedo earlier in the day. The admiral aboard the Italian flagship Vittorio Veneto wrongly believed the British to be 90 miles astern of him and failed to appreciate the risks involved in detaching the Zaras. He condemned his cruisers to a terrible end.

Prior to the battle of Matapan, the Warspite picks up her Swordfish floatplane on the run. Illustration by Dennis Andrews.

As the British battleships opened fired on their unsuspecting targets at point blank range, the destroyer HMS Greyhound highlighted an enemy cruiser with her searchlight – it was the Fiume (third in line). Warspite’s searchlights also lit up the enemy. The Italians were paralysed. Five of Warspite’s initial six shells hit an enemy cruiser just below the upper deck. Cunningham described this unfortunate vessel as ‘hopelessly shattered’. The other Italian ships were also destroyed causing great slaughter among their wretched, panic stricken crews.

A searchlight from the destroyer HMS Greyhound lights up an Italian warship that is destined to be destroyed during the March 1941 night action off Cape Matapan. Illustration by Dennis Andrews.

The Royal Navy was cast as the victim, however, in the summer of 1941 when the Germans sent the Luftwaffe to reinforce the Italians. The injuries suffered by the RN in first defending Crete from seaborne invasion and then evacuating Allied troops were dreadful.

Between May 21 and June 1 three cruisers (Gloucester, Calcutta and Fiji) and six destroyers (including Kashmir and Kelly of Captain Louis Mountbatten’s squadron) were sunk. Two battleships (Warspite on May 22 and Barham on May 27), a carrier (HMS Formidable), five cruisers and five destroyers were badly damaged. Two thousand British sailors were killed.

At shortly after 1.30pm on the afternoon of May 22 swarms of enemy aircraft descended on Warspite from all angles. A trio of fighter-bomber ME-109s plunged out of the flak from about 800ft up and straight at the ship. Turning hard to port, Warspite managed to evade two bombs but a third hit on the starboard forecastle deck and caused immense damage.

The semi-armour piercing 500lb bomb had blown a 4-inch gun mounting over the side, along with its crew, ripped up nearly 100ft of the forecastle deck and sliced open 50ft of the ship’s side like a can opener. It caused a flash fire in the starboard 6-inch gun battery. This was soon raging out of control, while flames and thick smoke invaded a boiler room via a ventilation shaft, forcing it to be abandoned. Thirty-eight men, including an officer, were killed or would die later from wounds. Thirty-one were wounded.

It was decided Warspite should go to Bremerton in the USA for repairs. While America was still neutral, it was assisting the British by offering docking facilities secure from enemy bombers. A month after getting back from Crete – and the night before she left for the USA – Warspite suffered more damage when a 1,000lb bomb exploded under her during an air raid on Alexandria.

ON December 7 the Japanese launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and fear of a follow-up assault on the west coast of the USA caused pandemonium. Anything seemed possible. Japanese carriers could be lurking off Bremerton.

Warspite, the American battleship USS Colorado (also under refit) and USN destroyers provided the only defence against air-attack the ill-prepared Puget Sound Naval Yard possessed. Warspite’s anti-aircraft gun crews were sent to action stations. Unfortunately, they didn’t have any ammunition for their weapons so a truck was sent off at top speed to get some. After a short while Warspite’s gunners were stood down. The British battleship recommissioned on December 28 and prepared to leave her American friends behind.

Warspite remained in North American waters throughout most of January 1942, carrying out sea trials under close escort from Canadian and American warships. She would soon be ordered back to the front line, although not in the Med, but rather in the Indian Ocean. She would only narrowly avoid destruction at the hands of the Japanese.

In stormy seas off the west coast of the USA, a US Navy destroyer escorts Warspite during sea trials (post her refit at Puget Sound in 1941/42). Illustration by Dennis Andrews.

* This article is also published in the February 2014 edition of WARSHIPS IFR magazine (published January 24). In the next part of this series (also to be published in the March 2014 edition of WARSHIPS IFR) we follow Warspite through the final years of her fighting life right up to her end of days on a beach in Cornwall.

Valiant ‘spite

explodes into life

The artwork illustrating this feature is by the Assistant Editor of WARSHIPS IFR magazine, Dennis Andrews. He first produced the images for ‘Warspite’ by Iain Ballantyne, which was published in its original hardback edition in 2001. They featured again in the paperback edition (published 2010, also by Pen & Sword Books).

Both Iain and Dennis had long discussions about the episodes that might be depicted to illustrate best the battleship’s fighting life. Dennis also contacted veterans of the various actions Warspite was involved in during WW2 to gain further insight into the reality of those events. Produced in oils, watercolour and also digitally, the illustrations form a distinct and historic chronicle, linking us directly with those events of two world wars. For more on the art of Dennis Andrews (including other material used in Iain Ballantyne’s book) visit: www.dennisandrewsart.co.uk

To read Warspite’s

incredible story in full

Buy the book