Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson’s vow in the House of Commons that Russia would receive a ‘robust response’ from the UK if it had a hand in the attempted assassination in Salisbury of an ex-military intelligence officer (and one-time double agent) would not have caused much fear in Moscow.

Prime Minister Theresa May’s subsequent demand that the Kremlin explain how a military grade nerve agent came to be used in a Wiltshire community was met with angry denials that it had anything to do with Russia. Moscow demanded that the UK stop inventing so-called fairy tales and hand over a sample of the Novichok nerve agent allegedly used in the attack for analysis in Russian labs.

Where the stand-off would go next was uncertain at the time of writing.

Strong words of condemnation, chucking a few diplomats out of Britain or withdrawing the England team from a footie tournament – the World Cup, due to be held later this year in Russia – would just make President Putin snigger at the continuing weakness of an old Cold War foe the Russians used to respect.

One of the major reasons they took Britain seriously once upon a time was its ability to carry out operations in a part of the world Moscow considers home turf, though not via alleged assassination plots in quiet cathedral cities.

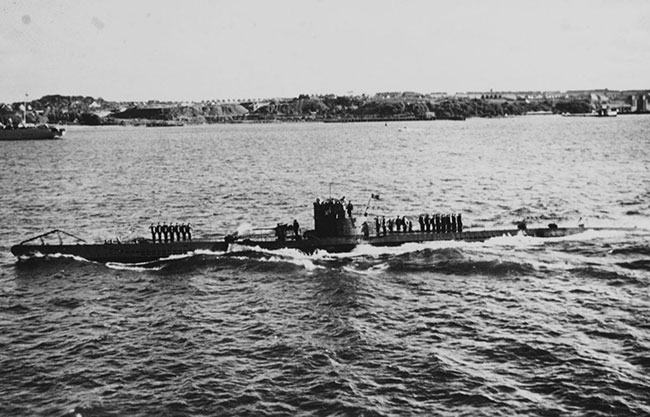

The UK’s deep cover operatives were submariners, with Prime Ministers from the late 1960s to the 1990s frequently giving personal authorization to send nuclear-powered attack submarines into the Barents Sea.

The sails of the US Navy attack submarines USS Connecticut and USS Hartford break through the ice on March 10 as part of ICEX 2018, which also, for the first time in some years, involves a British submarine. Photo: US Navy.

That is where they should be today, gathering intelligence on Putin’s new sea-based missile capabilities, which he is using to threaten the West. They should be trying to detect the Russian Navy’s increasingly formidable nuclear attack submarines as they break out into the Atlantic to menace the UK directly. They also need to trail Russia’s conventional submarines as they deploy to go and fire cruise missiles into Syria or, in future, other cauldrons of war and misery the Kremlin might seek to exploit for strategic advantage. British submarines must return to the shadow game of tracking and trailing Russia’s submarines as they try to interfere with NATO operations, plus seeking out its nuclear missile craft, which are poised to strike at all times.

A submariner keeps watch from the sail of the attack submarine USS Hartford after the boat has surfaced through the ice in the Beaufort Sea during ICEX 2018. Photo: US Navy.

However, the UK no longer maintains a presence in Arctic waters with surface warships or submarines at a level that would ever worry Moscow. This is due to successive governments hollowing out the Royal Navy’s fighting capabilities, cutting its people and warships back to the bone and failing utterly to maintain a strong enough submarine force. Increasingly it is other nations – and in the case of Canada using submarines that the UK sold off as it felt it wouldn’t need them – taking up the strain and sometimes performing a job the Royal Navy did so well.

Britain’s submarine warfare proficiency was once the envy of not only the Russians but also the Americans. It is why novelist Tom Clancy said of the Royal Navy’s submarine force during the Cold War: ‘While everyone deeply respects the Americans with their technologically and numerically superior submarine force, they all quietly fear the British.’

Britain does maintain a reputation for excellence in undersea warfare – and right now it has deployed its first submarine for some years to exercise under the Polar ice with the Americans – but there remains severe lack of submarines, a shortage of people and lack of funding to stay at sea that undermines all that (and the UK’s standing in the world).

The will-they-won’t-they pantomime over the question of whether or not Britain will build a seventh Astute Class attack submarine is a good illustration of how UK governments in recent years have turned global fear (and respect) of the Royal Navy into something approaching derision (among both friend and foe). NATO allies are mystified and deeply saddened by the self-inflicted destruction of the British fleet.

The recent hokey-cokey act over the Astutes followed claims the UK’s amphibious warfare forces are to be disemboweled in yet another round of defence cuts. It was suggested that the extremely capable assault vessels HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark are to be axed and sold off – and the government has still not denied it may happen. On top of that at least 1,000 elite Royal Marine commandos might be given their marching orders. Those specialist ships and highly-trained commandos are key elements in the defence of NATO’s northern flank against potential Russian aggression, so Moscow has no doubt been delighted with the idea (at a time when it is building up its own amphibious forces).

With the future of the UK amphibious ships and Royal Marines far from settled the Astute submarine farce then unfolded.

President Putin is, as explained in the final section of my new book ‘The Deadly Trade’, deploying submarines to shock and awe the world – via missile boat diplomacy – and will have been very pleased to hear the UK might only build six Astutes. He has given orders for Russia to construct a dozen new Yasen Class attack submarines (a development of the formidable Akula) and so the dithering over the seventh Astute will have been music to his ears.

The once mighty Royal Navy, having recently been reduced to sending out plastic mine-hunters and fishery protection vessels to shadow Russian naval task groups passing close to British shores (due to a chronic lack of frigates and destroyers), was providing further evidence of a paper British lion. It can roar and bluster about ‘robust action’ but it currently has not much naval muscle left to do anything meaningful by way of conventional deterrence.

Nonetheless, on March 6, the Ministry of Defence was delighted to issue a confirmation that the seventh Astute Class submarine will indeed be built – giving the so-called good news to finally bury the potential bad news its own indecision and history of defence investment failures had created in the first place.

The Astute Class attack submarine HMS Ambush during Exercise Dynamic Manta 2015. The Arctic should once again become a major focus for British and NATO submarine operations. Photo: NATO.

In a written statement to the House of Commons, the day after the Salisbury alleged assassination story hit the headlines, defence procurement minister Guto Bebb was pleased to reveal the UK government would fund the seventh boat.

However, you have to ask what the point is of promising to construct a seventh submarine when it has been revealed by the National Audit Office that, during construction of earlier submarines, the process was badly delayed by some of their equipment being transferred to the few Astutes already in service – robbing Peter to ensure Paul can stay at sea.

And what is the point of building new submarines if you can’t recruit enough submariners to take them to sea? It is no secret that attack boat crews the UK needs to be out there – showing Russia it can’t have it all its own way – are being transferred into the Trident missile vessels just to keep them on deterrent patrol. Which means the attack boats cannot always deploy to exert their presence in waters close to Russia, or anywhere else.

It’s a disgraceful shambles and no way to manage a navy. Promises of a seventh Astute Class submarines are nothing but window dressing for a crisis in national defence that the government so far shows no inclination to really sort out.

The reality is that seven Astutes are not enough, but for the first time in more than a century Britain is not building any other kind of attack submarine as a follow-on or alternative. Ensuring the UK has enough nuclear-powered attack submarines it can send into Russian home seas – staying in international waters of course – in order to carry out some espionage on Moscow’s growing missile might and expanding submarine force is the answer. Having a dozen boats means the UK will be able to deploy up to half a dozen at a time globally, including some allocated to the Arctic. This will not only counter Russia’s recent cheeky submarine forays close to the UK but also tell Putin that a line has been drawn against transgressions elsewhere (at sea, in the air or on land).

The Royal Navy attack submarine HMS Tireless sits on the surface of the North Pole during ICEX 2004. Back then the British fleet operated 11 attack submarines, and today it has half a dozen in commission. Photo: US Navy.

If Russian attack submarines again come into waters close to the UK – seeking out the Royal Navy’s Trident deterrent submarine as they deploy on patrol from the Clyde, or sticking two fingers up to Britain by making fast, submerged transits of the Irish Sea – it should be answered robustly alright.

Putin needs to know that the British fleet will return to its perfectly legal pursuit of sending anti-submarine and intelligence gathering frigates, plus attack submarines, into the Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea. The Russian Bear must find himself chasing his tail in his lair rather than snarling unchallenged in the face of the West.

‘THE DEADLY TRADE: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’ (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25.00, hardback) has just been published and is a follow-on to ‘Hunter Killers’ (Orion Books, 2013) which told the story of Royal Navy submariners undertaking dangerous missions against the Soviet Union across the Cold War.

‘THE DEADLY TRADE: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’ (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25.00, hardback) has just been published and is a follow-on to ‘Hunter Killers’ (Orion Books, 2013) which told the story of Royal Navy submariners undertaking dangerous missions against the Soviet Union across the Cold War.

While working as a newspaper defence correspondent Iain sailed into the Barents Sea aboard a British anti-submarine frigate, during the warship’s special diplomatic mission to visit Murmansk and Archangel. At the end of the Cold War he also visited the other restricted Russian naval bases zones of Kronstadt and Sevastopol. He has twice been under the sea in nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine and is the founding and current Editor of the globally read naval news magazine WARSHIPS International Fleet Review. www.warshipsifr.com

‘The Deadly Trade: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (752 pages, hardback £25.00/eBook £12.99) It is available via Amazon

‘The Deadly Trade: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (752 pages, hardback £25.00/eBook £12.99) It is available via Amazon