Crimean Steal of the Century

(Does Russia Want to Annex Ukraine’s Aircraft Carrier Construction Yard?)

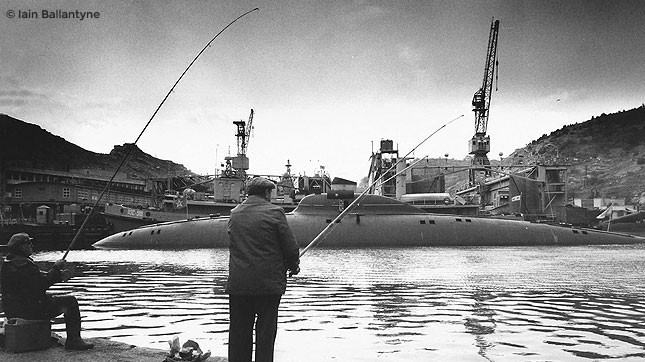

by Iain Ballantyne with Usman Ansari

It was the last stand of the Ukrainian Navy. Try as they might, Russian forces for a long while failed to take the mine warfare vessel Cherkassy. Several times the Russians tried to storm aboard in a hail of stun grenades and gunfire while intimidating Mi35 helicopter gunships clattered overhead, but the defiant Ukrainians held out.

Every other Ukrainian vessel in the Crimean peninsula had been taken over with many sailors and marines defecting to the new Russian rulers. Yet the nearly 62 crew of the Cherkassy, a beefy 750 tons ship armed with 30mm cannons and machine guns in addition to rockets, begged to differ (and in the absence of any specific orders on what to do from their naval headquarters).

Valiant mine warfare ship Cherkassy, the last Ukrainian naval vessel in the Crimea to yield control to the Russians. Photo: Cem Devrim Yaylali. © Cem Devrim Yaylali, 2013. For more by Cem Devrim Yaylali visit http://turkishnavy.net

Despite the bangs and flashes, lethal force was not unleashed by either side, with Cherkassy’s men using powerful water jets to hold potential boarders at bay, also dropping low power charges around their ship as a deterrent.

The Russians used a sunken ship – seemingly a Ukrainian mine-sweeper – to block the channel leading from the Donuzlav Lake into the open ocean on the western side of the Crimea. Having failed in her attempt to tow the block ship out the way, Cherkassy continued cruising around and around until, finally explosives wrecked her steering during one assault by the Russians. This left her ethnic Ukrainian commander, Captain Yuri Fedash, with three choices: Go out in a blaze of glory by using his weapons on the Russians; scuttle the Cherkassy; surrender. Some of the vessel’s complement had already wavered, with Capt Fedash allowing a dozen of those men to disembark peacefully.

Stormed successfully by Russian naval infantry, the end finally seemed near for the defiant Cherkassy. Capt Fedash ordered his men below decks and told them to seal all hatches while he tried to negotiate with the invaders. Admiring the clever tactics of the Ukrainians – and their efforts to avoid bloodshed – the Russians agreed to let Fedash and some of his officers have one last ward room dinner aboard before pulling down the Ukrainian ensign in the morning.

This was in marked contrast to the treatment handed out to other Ukrainian vessels. Twelve of the Ukrainian Navy’s 17 major surface combatants were seized peremptorily by Russian forces along with the bulk of naval aviation assets and sole submarine. Ukraine also lost its combat dolphins. The dolphin programme aimed at training the intelligent and fiesty mammals in countering combat frogmen and also detecting underwater objects such as mines. After a long period of stagnation, the programme was revived for the Ukrainian Navy in 2011 after years of being used for civilian purposes, but still suffered from a lack of funding. The Russians are likely to pump money in. Ukraine has also lost most of its significant naval and marine corps bases and other key defence facilities. Of the 15,450 naval personnel, 12,000 were stationed on the Crimean peninsula. The majority of these are believed to have defected to Russia or resigned from the service. Those that have chosen to continue under Kiev had to make their own way back to territory under Ukrainian control.

While warships were blockaded in port and seized, some of the Ukrainian Navy’s aviation assets managed to escape. These included a Kamov Ka-27PL and three Mil Mi-14PL maritime helicopters, a Beriev Be-12 amphibian, and two Antonov An-26 transport aircraft. Aircraft undergoing maintenance had to be left behind. The tattered remains of the Ukrainian Navy are now based in the port of Odessa, including its most capable ship, the Krivak III Class frigate Hetman Sahaydachny. Ukrainian access to the Sea of Azov has been cut by Russian occupation of Kerch, leaving Kiev’s eastern ports marooned. Just how Kiev plans to reconstitute its maritime capabilities is uncertain, but given the prevailing East-West tensions it is possible surplus equipment from NATO states could be transferred.

Western action could also have a direct effect on the Russian Navy, with Paris contemplating blocking the transfer of two Mistral Class amphibious assault carriers being built under contract in France. The first of those vessels, Vladivostok, was due to reach Russia by the end of 2014. The second, the somewhat fatefully named Sevastopol, was due to arrive next year and join the Black Sea Fleet (BSF).

Though a series of sanctions have been announced against selected Russians and Russian interests, the Mistral deal was not at the time of writing cancelled. The French view the ships as commercial vessels due to them currently lacking weapon. systems. Should Russia move to take further parts of Ukraine or the Russian ethnic enclave of Trans Dniester in Moldova, the amphibious assault ships may be included in a new set of sanctions. Meanwhile, in Kaliningrad – the former East Prussia, annexed by Russia in 1945 and also host to a major naval base at Baltisk – the Yantar shipyard has just launched Russia’s first Project 11356 frigate. The Admiral Grigorovich is a 3,850 tons multi-role vessel capable of independent or combined Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW), Anti-Air Warfare (AAW), or Anti-Surface Warfare (ASuW) missions. The lead ship of a class of six slated, they will be assigned to the Black Sea Fleet (BSF) along with new generation submarines.

Some in the West may be puzzled by all the focus on the Black Sea for Russian naval forces and territorial expansion, but that is because the democratic leaders of Europe think in terms of exerting influence via aid packages and trade, keen to export liberal ideals of freedom. President Putin thinks in hardball terms. Last month (March) he gave a speech in the spectacular St. George’s Hall of the Kremlin.

President Vladimir Putin during his historic speech last month (March) in the Kremlin.

Photo: Office of the President of RussiaIt placed the issue of the strategic naval base of Sevastopol at the heart of his nation’s annexation of the Crimea. President Putin told his audience he feared that, without Russian intervention, the Ukraine would soon have become a fully paid up member of the West.

This would have placed a potentially hostile military organisation close to the heart of the Rodina, the Russian motherland. The former KGB officer told his audience: “What would this have meant for Crimea and Sevastopol in the future? It would have meant that NATO’s navy would be right there in this city of Russia’s military glory, and this would create not an illusory but a perfectly real threat to the whole of southern Russia.”

Putin followed this with a drily humorous statement: “But let me say too that we are not opposed to cooperation with NATO, for this is certainly not the case [but] we are against having a military alliance making itself at home right in our backyard or in our historic territory.” He went on: “I simply cannot imagine that we would travel to Sevastopol to visit NATO sailors. Of course, most of them are wonderful guys, but it would be better to have them come and visit us, be our guests, rather than the other way round.” Putin in his March speech described Sevastopol as “a legendary city with an outstanding history, a fortress that serves as the birthplace of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.”

He also said: “Crimea is Balaklava and Kerch, Malakhov Kurgan and Sapun Ridge. Each one of these places is dear to our hearts, symbolising Russian military glory and outstanding valour.” There was, as ever, hard-nosed strategic interest at stake for Russia, which seeks to prevent the Assad regime from collapsing via arms shipments from the Black Sea.

The BSF is also a counter to NATO’s new Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) ships patrolling the Mediterranean and elsewhere. This month (April) a Russian fighter jet repeatedly buzzed one of those BMD ships, USS Donald Cook, as the Arleigh Burke Class destroyer sailed in the Black Sea, bound for NATO exercises. See the forthcoming (June 2014) edition of WARSHIPS IFR (out on May 16) for more on that incident.

Putin’s predecessors in Russian doll form (from right to left): Brezhnev, Gorbachev, Lenin and Yeltsin (who presided over Russian post-Cold War decline). This set of dolls was purchased by Iain Ballantyne at Sevastopol in 1991. Image: Strathdee Collection.

In some ways the Cold War never ended – the past 23 years have been but a pause in the overt, muscular rivalry between Russia and the West. And can President Putin tolerate even eastern Ukraine being still under the Kiev government’s control, despite what he says today about no further moves? The majority ethnic Russian population of eastern Ukraine may one day soon provide the Kremlin with an excuse to protect them, but under the skin it will again be about strategic necessity for Russia.

Not only would it ensure that NATO cannot get any closer on the northern shores of the Black Sea it would once more bring under Moscow’s control the industrial resources of the Donetsk region and also, crucially, the Black Sea Ship Yard at Nikolayev. If the Russian Navy is to progress with its regeneration, the addition of such a ship construction facility – which built all the Soviet Navy’s helicopter and aircraft carriers – would be a key addition.

The Kremlin has often stated it wants to build half a dozen new strike carriers but currently lacks the major surface ship construction capacity and skills to do so. The new carriers are unlikely to be built at Sevmash on the White Sea, which recently completed a very troubled and prolonged reconstruction of the former Soviet carrier Gorshkov for India, not least because its roster is packed with new submarine orders.

A port beam view of the Russian aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov en route from her construction yard at Nikolayev on the Black Sea for duty with (what was then) the Soviet Northern Fleet. The same design of ship today serves in the Russian, Indian and Chinese fleets. Photo: US Navy.

An astern view of the Kuznetsov with a strike jet and helicopter on her large flight-deck.

Photo: US DoD.

The extant strike carrier of the Russian Navy, the Admiral Kuznetsov, was built at Nikolayev. Even the Chinese Navy’s new carrier was built there.

Launched in 1988 and originally to be called Riga, her name was changed to Varyag before the almost complete vessel was sold to a Chinese commercial company in 1998. At one point allegedly destined for use as a floating casino off Macau, ultimately the former Varyag was reconstructed in a Chinese naval shipyard.

Today she is China’s first aircraft carrier, named Liaoning. Ukraine’s sale of that vessel to China, now deploying her regularly as a symbol of growing maritime might (with more, home-grown, carriers rumoured) must have deeply angered many in the former Soviet Union and really dented their pride. They now find their former carrier construction yard tantalisingly not far from the newly reclaimed Crimea. All Putin needs is the excuse of safeguarding ethnic Russians to annex Nikolayev too.