From Cold War Warrior to Depicting the Fury of WW2

His experiences as a Cold War submariner must surely have influenced Hollywood movie director David Ayer when it came to writing and directing the gritty WW2 drama ‘Fury’.

Movie director and former USN submariner David Ayer (left) on the set of ‘Fury’ with Hollywood star Brad Pitt. Photo: Giles Keyte/Sony Pictures.

It features a young, virgin soldier plunged into the brutal world of savage tank warfare as the conflict reaches its bloody, desperate end. His surly comrades are tough guys in the tight confines of a Sherman, surrounded by complex machinery. Their lives depend on him not cocking things up.

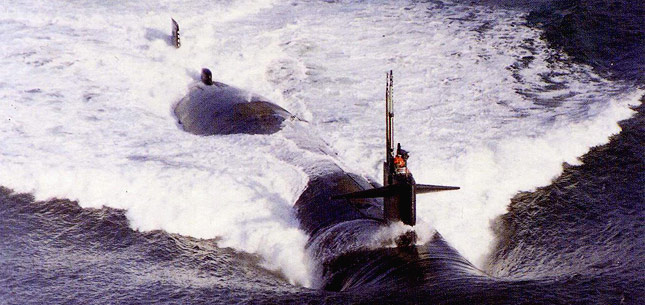

USS Haddo at sea during the Cold War. Photo: US Navy.

Ayer was plunged into a similar environment as a teenage sailor, serving as a sonar man aboard the US Navy nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Haddo. During a recent interview in the UK’s Guardian newspaper Ayer pondered his fledgling submariner days, comparing them with the baptism of fire he gave to the young soldier at the core of the narrative in ‘Fury’.

“It’s very difficult to show up as a new guy because you don’t have a job, you don’t know the equipment and you’re training for life and death,” Ayer told the Guardian. “You could make a mistake that could kill people, so you won’t be trusted until you are tested.” Ayer revealed that it is an “incredibly intimidating” situation to be in and a lonely place to be where there are no sentimental words of encouragement to take the edge off the harshness.

The needs of the unit, in his case a Permit Class SSN going up against the Soviets in the cold, dark ocean during the mid-1980s, overruled any personal weaknesses he might fear and so he measured up to the mission. After an honourable discharge from the USN, Ayer began writing movie scripts and while one work, entitled ‘Squids’, drawing directly on his time as a submariner, has not yet been produced, his ‘U-571’ was filmed.

To write it Ayer drew not only on his Cold War submarining experiences but also adapted true-life episodes involving the Royal Navy’s legendary WW2 secret captures of German Navy Enigma encryption machines and other materials. The only problem was that with ‘U-571’, Ayer’s script transformed these British exploits into daring deeds by the US Navy. This was something that (bearing in mind he was an American working on a Hollywood movie primarily for US audiences) he felt he had to do.

In an interview with BBC Radio 4 in 2006, Ayer confessed that the ‘U-571’ storyline was “a distortion”. Furthermore, he explained, it was “a mercenary decision to create this parallel history in order to drive the movie for an American audience.” However, there were efforts by Ayer and the movie makers to draw on the firsthand experiences of the men who carried out the secret captures, especially those involved in taking U-110 off Iceland in May 1941.

In the movie U-571 a German U-boat captain (Thomas Kretschmann) ponders where his enemy lurks while a shipmate awaits his verdict. Photo: Universal Pictures.

Ayer told the BBC: “I met with the Royal Navy officer who actually went down into the U-boat and recovered the Enigma machine in 1941.” This veteran, David Balme, who was a junior officer in the destroyer HMS Bulldog, understood that it was necessary for a movie such as ‘U-571’ to Americanise things. “He seemed OK with it,” said Ayer, “he was a great guy, but I understand how important that event is to the UK, and I won’t do it again.”

Even Prime Minister Tony Blair intervened, complaining the movie was an affront to the British war record. Eager to offset the storm over their story, the movie’s makers took Mr Balme to Malta to act as a technical advisor during filming. There he met the stars, including Matthew McConaughey and Harvey Keitel and found them congenial company. Balme felt the end result was a pretty good effort and as a gesture to the British origins of Ayer’s tale the end credits included a tribute to the Royal Navy and its capture of U-110 and the Enigma material.

This year during the promotional tour for ‘Fury’, which stars Brad Pitt as war grizzled tank commander ‘Wardaddy’ and fresh-faced Logan Lerman as novice tanker Norman Ellison, it was clear attention to detail had been important.

Combat action in the WW2 tank combat movie ‘Fury’. Photo: Giles Keyte/Sony Pictures.

Before filming began in the UK ex-US Navy SEAL Kevin Vance and former British Army tank corps soldier David Rae put the principal cast members through a gruelling boot camp. Rae later explained the rationale behind this: “The cliché is ‘no rank in a tank’ – we all know who the boss is, and we know where the line is and wouldn’t cross it, but we’re very, very close to each other. You know everything about each other. You look after each other. It’s a brotherhood, within a tank.” That all sounds very similar to the working life of submariners, which I delved into for my book ‘Hunter Killers’ of course.

See the forthcoming December 2014 edition of WARSHIPS International Fleet Review magazine for a hard copy version of this article. Out from November 21 and available from branches of W.H. Smiths or direct from HPC Publishing.