‘Bismarck was being mercilessly pounded’

As the sun peeped over the eastern horizon on 27 May 1941, to reveal a storm-tossed seascape, from his upper deck position aboard HMS Cossack, teenage rating Ken Robinson scanned his surroundings.

Aboard Ken’s ship and other destroyers in the 4th Flotilla, tired, red-rimmed eyes studied the horizon, trying to sight the enemy, who must be nearby but was not yet visible. This was most likely, so the destroyer men thought, because Bismarck was lurking in a squall and preparing to blow them out of water.

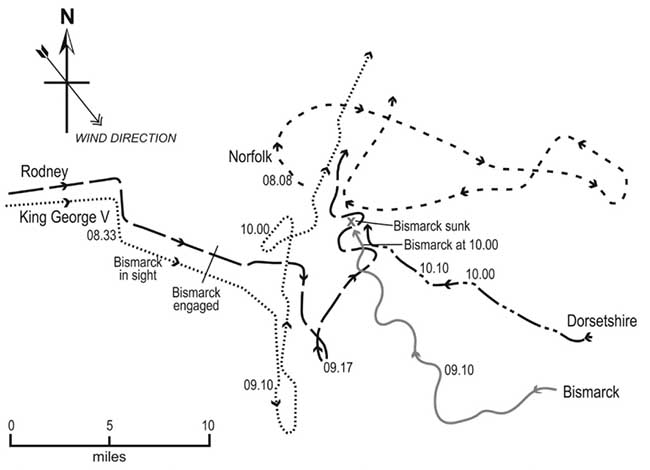

How the brutal final gunfight between Bismarck and the British warships unfolded. Image: Dennis Andrews.

Then the German battleship was spotted 8,000 yards dead ahead of HMS Zulu, so she and the other 4th Flotilla’s ships turned away to loiter at what they hoped was a healthier distance. From Cossack, Captain Philip Vian reported in a signal to Home Fleet boss Admiral John Tovey, at 7.01am, that Bismarck had opened fire, but failed to score any hits.

In the aftermath an eerie calm settled over the scene. The weather cleared to present what an officer in Zulu described as ‘a bright blue sky and a clear horizon had taken the place of the grey mists and driving clouds.’ In the German battleship, there was no pleasure taken in the same vista, for it meant the approaching enemy would have a good view to a kill.

The battleships HMS King George V and HMS Rodney soon arrived and the final battle began as their big guns roared, with Bismarck’s return fire inaccurate and causing no serious damage to any British vessel.

The battleship HMS Rodney closes in on the Bismarck, burning in the distance, during the final battle of 27 May 1941. Image: Dennis Andrews.

After her long dash north through heavy seas, bows plunging into gigantic waves and shaking them off before the ship hurtled on, the cruiser HMS Dorsetshire finally came within range of her quarry. George Bell waited on the Dorsetshire’s bridge to carry messages from Captain Benjamin Martin around the ship. Like every man in the British warship, George knew the task at hand was absolutely necessary: “We closed to open fire, for the last thing we wanted was to allow Bismarck under any circumstances to cause havoc among our convoys.”

Amid the bombardment by the big 16-inch and 14-inch guns of Rodney and King George V, rapid-fire salvoes of 8-inch shells from the Dorsetshire and also cruiser HMS Norfolk hurtled towards the German battleship, ripping her upper works to shreds. Some of the heavy shells, meanwhile, punched holes right through Bismarck, while others tore off parts of the superstructure or inflicted mortal damage.

From one of Rodney’s 6-inch gun turrets Royal Marine Len Nicholl looked on in fascinated horror: “I actually saw the back of the [Bismarck’s] B turret explode when one of the shells hit her. It just flipped up in the air, spinning like a penny.” He added: “I was on the port side of the ship. We’d go up the port side firing at her, turn around and then the starboard side would have a go at firing. We would be in a bit of a lull on the port side. I saw Bismarck burning from stem to stern and she was a beautiful ship, beautiful schooner bows on her.”

As the fight neared its end, Swordfish from HMS Ark Royal appeared overhead and, after being fired on in error by HMS King George V, were told to keep their distance and to not attack Bismarck with torpedoes.

Torpedo retained by its frustrated crew a Swordfish torpedo-bomber flies away from the scene of the Bismarck’s destruction. ++

The young aviators, including Terry Goddard, had launched from Ark Royal with their spirits high but what they saw below took the edge off any triumphalism they may have felt on take-off. “We were at about 2,000ft,” recalled Terry. “Bismarck was surrounded by battleships, cruisers and destroyers. She was being mercilessly pounded. Her A turret was gone. The after turrets were still firing. She was steaming at about seven knots, if that. The bridge was gone…there was just a big black hole billowing black smoke. She was a mess and the gunfire was just ceaseless…”

The final blows from the British were delivered by torpedoes after all, launched by HMS Dorsetshire, which went in close after the Rodney and King George V ceased fire. Bismarck survivors would later claim that they had scuttled the ship and this is what finally put their ship out of her misery, rather than the cruiser’s torpedoes.

The heavy cruiser HMS Dorsetshire launches a torpedo. Photo: Courtesy of the HMS Dorsetshire Association.

Either way, Capt Martin ordered a signal sent from Dorsetshire as ‘Most Immediate’, which told the world of the German battleship’s end and her bravery as she went down: ‘Torpedoed Bismarck both sides before she sank. She had ceased firing but her colours were still flying.’

The aftermath of Bismarck’s sinking saw desperate calls for salvation from hundreds of survivors fighting to stay afloat amid oil and debris in a strength-sapping cold sea. Capt Martin gave the order for Dorsetshire to stop by the biggest group and start rescuing them, despite fears of U-boat attack and the likelihood of a Luftwaffe assault.

George Bell later pondered how there never was any personal enmity for the foe: “When we went to pick up survivors, we did so because they were seamen doing their job of work, just like us. We had done our job, which was to sink the Bismarck and so now we offered them mercy.”

However, it all came to a halt 20 minutes after it started, when there was a submarine scare, Captain Martin giving the order for slow ahead to remove Dorsetshire from peril. The cruiser slid through floating knots of Germans who cried out in despair, faces etched with agony as their only means of survival pulled away.

Horrified British sailors staring over the side knew they were leaving fellow mariners to a slow, excruciating death. George brought orders from Capt Martin for them to throw lifebelts and anything else that would float overboard to give the Germans a chance to stay afloat.

Casting his mind back, Cossack’s Ken Robinson recalled that by the time the fighting was over that day, all he and his shipmates wanted to do was get some sleep. “What we needed above all was to get our heads down,” he recalled. “Cossack was always in the thick of it and it was only the latest episode in an exhausting war.”

• To read more of how a band of brothers took on the German battleship in the final battle of 26/27 May 1941 read ‘Bismarck: 24 Hours to Doom’ published by Agora Books and available via Amazon as a e-book or hardcopy in the UK and also the USA

• Iain Ballantyne tells the story of the Bismarck Action from various points of view across three of his books – ‘Bismarck: 24 Hours to Doom’, ‘Killing the Bismarck’ and ‘HMS Rodney’ (the latter two published by Pen & Sword). All three convey the stories of people in the big ships, along with major twists and turns, while also providing the perspective of destroyer and cruiser sailors, along with aviators. More information on Iain Ballantyne’s books here.

++ A composite image using a Swordfish photo by Jonathan Eastland http://www.ajaxnetphoto.com and the Paul Wright painting ‘The End of the Bismarck’ that features on the cover of ‘Killing the Bismarck’. More details on Paul’s work here http://www.battleshippaintings.com