D-Day Navies Pt2: HMS Rodney’s accidental bombardment

Fulfilling her role of heavyweight bombardment reserve, the battleship HMS Rodney trailed behind the first wave of invasion shipping. She was to hang back during D-Day and conduct a bombardment only if called in by assault force commanders. The way things turned out, however, her mighty 16-inch guns did roar after all, though not quite in the fashion anticipated.

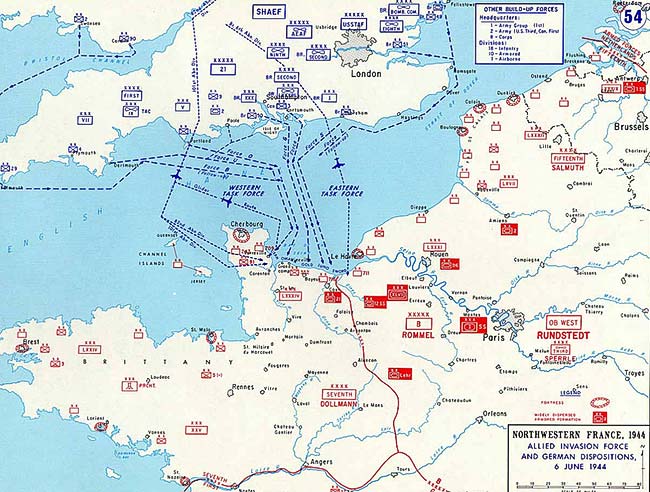

The Germans had laid extensive minefields off the Normandy coast and channels had been swept clear at both the eastern and western ends of the invasion front. HMS Rodney ended up entering the eastern swept channel, heading for Sword sector but could not expect freedom of manoeuvre until she reached the more open areas, off the actual invasion beaches.

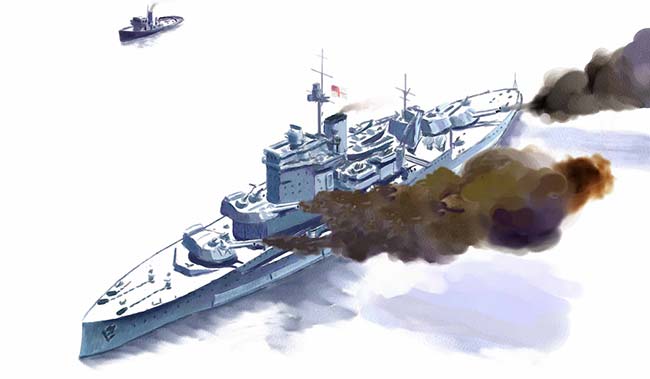

The 16-inch gun-armed British battleship HMS Rodney in her distinctive late WW2 paint scheme, around the time of the invasion of Normandy. Photo: Strathdee Collection.

Midshipman Roger Morris was closed up in the port fore 6-inch gun director and – with the ship getting closer to the invasion beaches – he and his shipmates found they could ‘pick out the warships all together in a group, [with battleship] Warspite prominent with her high bridge and large funnel. She appeared to be firing in a southerly direction at some target or other.’

Junior rating Allan Snowden, working on the upper deck, was thunderstruck, thinking: ‘the sheer volume of noise… the blast of the guns, was incredible and you could feel it through your body even if you were quite a distance from the gun actually doing the firing. A bit nearer the coast were these rocket ships, which were like huge landing craft. When they fired it was like Guy Fawkes’ night and you would see their rockets whooshing off into the air. You couldn’t help feeling a bit sorry for the guys on the receiving end.’ Adding to the cacophony were the roaring engines of wave after wave of Allied fighter aircraft zooming overhead, headed to rocket and strafe targets inland.

A convoy of landing vessels sails across the English Channel toward the invasion beaches on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Photo: US Coast Guard Collection/ US National Archives.

Exiting the swept channel, HMS Rodney shouldered her way through landing vessels, causing them to scatter in alarm. Seeing the huge, and unexpected, bulk of Rodney nosing in among the confusion of shipping, the commander of the Eastern Task Force, Rear Admiral Philip Vian, flashed a signal from the cruiser HMS Scylla to Rodney. He ordered the battleship to ‘get the hell out of it’ and head for Portsmouth to await further instructions.

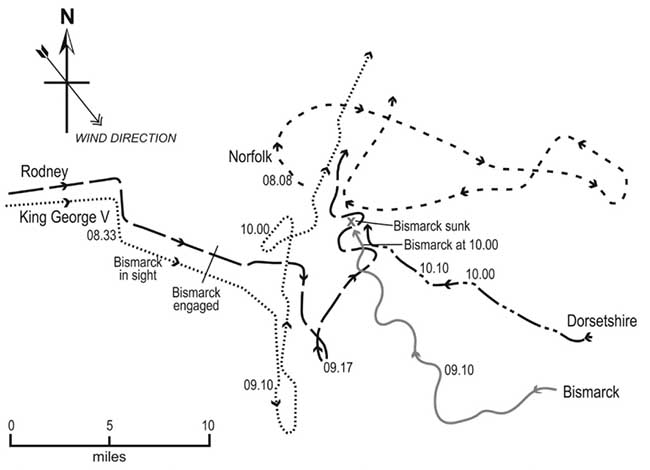

Turning back into the swept channel, she passed some landing craft escorted by a frigate, being shelled by a shore battery situated near Le Havre, a couple of 5.9-inch shells falling short. The frigate made smoke, so the frustrated German gunners turned their attention to Rodney. This attempt to hit his ship was also observed by Midshipman Morris, who recalled: ‘they dropped one shell over and one short. Action stations were sounded off and we fired two rounds of 16-inch armoured piercing in the general direction of the battery. No further fire ensued…’

However, the swept channel did a dogleg and this prevented the ship from continuing to bring her guns to bear. Writing in his journal that night Midshipman Tony Robinson recorded his own perspective on this very short action: ‘I presume that the morale [sic] effect of having 16-inch guns firing back at him was too much and he gave up. But we had fired our first shots in anger at the invasion which pleased everyone tremendously.’

Allied mine-sweepers clear mines off a Normandy invasion beach on June 6, 1944. Photo: US National Archives.

Late on the evening of D-Day the battleship HMS Warspite pulled back from Sword sector and dropped anchor a few miles offshore. The following day Warspite fired against likely German troop, vehicle and gun positions.

Bit by bit the Nazi grip on Normandy was being loosened. Having fired more than 300 shells in just two days, the Warspite’s magazines were exhausted so she also retired across the Channel to Portsmouth to load up with more ammunition.