First blood in longest struggle of WW2

When a state of hostilities between Germany and Britain was declared on 3 September 1939, the Royal Navy battleships HMS Nelson and HMS Rodney, along with other units of Home Fleet were spread along the most likely breakout routes for commerce raiders. However, the German pocket battleships Graf Spee and the Deutschland had already broken out into the Atlantic while Kriegsmarine U-boats were also on their war stations.

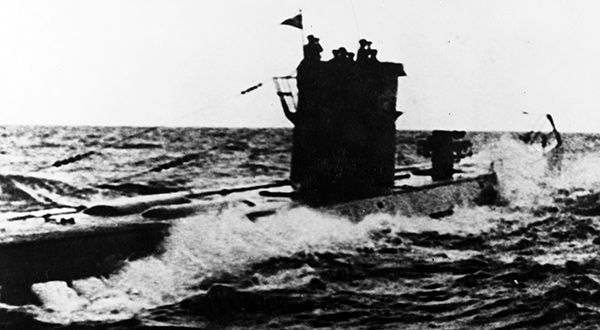

The Germans were not then operating a policy of unrestricted U-boat warfare and, when first blood in the new struggle for the Atlantic was taken by Oberleutnant Fritz-Julius Lemp (in command of U-30), it proved one of the most controversial episodes of the conflict.

A Type IX U-boat out on patrol in the early part of WW2. The first submarine lost during the conflict would be a vessel of this type. Photo: US Naval History and Heritage (NHHC).

U-30 attacked the liner Athenia, of 13,581 tons, on the evening of September 3, to the west of Ireland. She was carrying 1,013 passengers, including refugees, among them 246 American citizens attempting to reach home. Despite Athenia steaming at 12 knots and zigzagging to try and deter submarine attack, Lemp still caught the liner in his periscope.

The ship he was studying while trying to make up his mind was large, showing no lights and also outside the usual transatlantic liner route. Lemp decided she was an Armed Merchant Cruiser (AMC) and therefore a permitted target. He fired two torpedoes, inflicting a single mortal wound.

British warships and various merchant vessels made haste for the scene after a distress signal was picked up, but 119 people had lost their lives, including 28 Americans. This was very unwelcome news, for the Germans were keen to keep the USA neutral in the new conflict. The deaths of its citizens in similar incidents during WW1 had helped to bring America into that war.

Berlin maintained it could not have been a U-boat that was responsible, as such acts were forbidden by Adolf Hitler but even they privately suspected that it may, in fact, be the case. Athenia was the first Allied vessel sunk in WW2, during what would be the longest struggle in the latest global war. On U-30’s return home, Oberleutnant Lemp was flown to Berlin to brief the naval high command, confirming he had, indeed, sunk Athenia. Lemp was not court-martialed, for it was felt he had acted properly and in good faith.

HMS Ark Royal, which led an anti-submarine hunting group. Photo: NHHC.

Even so, U-boat force boss Admiral Karl Donitz was told the episode must be kept secret. Donitz ordered the relevant page of U-30’s log removed and replaced with a doctored one, which confirmed attacks on the enemy merchant vessels Blairlogie and Fanad Head. However, on the day Athenia was sunk the fake log book page recorded U-30’s position as 100 miles away from the scene.

Less than a week after Athenia’s sinking, newly appointed First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill issued orders for a convoy system to be introduced. To their credit, whereas in WW1 shipping companies were reluctant to tie themselves to the Royal Navy’s apron strings, in the new war they acquiesced immediately. For all that, in those early days there were still many ships sailing solo as they headed for friendly ports and which became victims of the so-called ‘grey wolves’ of Germany’s U-boat force.

For their part, the Germans suffered their first submarine loss on September 14, when Kapitanleutnant Gerhard Glattes of U-39 tried to attack HMS Ark Royal. Britain’s most modern aircraft carrier was leading a U-boat hunting group – but U-39’s torpedoes missed and escorting destroyers Firedrake, Faulknor and Foxhound pounced while Ark immediately exited the scene. The entire 44-strong crew of the U-boat was taken prisoner.

The aircraft carrier HMS Courageous, which was sunk on 17 September 1939 by U-29, a heavy blow for the British. She is seen here in summer 1937. Photo: AJAX VINTAGE PICTURE LIBRARY.

The loss of the carrier HMS Courageous three days later, sunk to the south-west of Ireland, proved the error of Britain sending out sub-hunting groups led by aircraft carriers. They were nothing but an ideal means to serve up much-prized targets on a plate, though the carrier-led hunting group concept would come to fruition for the Allies later in the war.

Kapitanleutnant Otto Schuhart of U-29 found Courageous after sighting one of her aircraft during a periscope look. He waited until the massive ship was compelled to follow a straight course to land an aircraft and torpedoed her. Within ten minutes of being hit, the Courageous was gone. Out of the 1,260 men in the ship’s company and embarked air squadrons, only 519 survived, picked up by destroyers and passing merchant ships. While the loss of Courageous and so many men was a bitter blow – also causing a change in direction for the British, who abandoned the hunting group idea – the real shocker was delivered the following month.

Kapitanleutnant Otto Schuhart of U-29 found Courageous after sighting one of her aircraft during a periscope look. He waited until the massive ship was compelled to follow a straight course to land an aircraft and torpedoed her. Within ten minutes of being hit, the Courageous was gone. Out of the 1,260 men in the ship’s company and embarked air squadrons, only 519 survived, picked up by destroyers and passing merchant ships. While the loss of Courageous and so many men was a bitter blow – also causing a change in direction for the British, who abandoned the hunting group idea – the real shocker was delivered the following month.