We Must all Pray ‘the Better Angels’ Prevail

As I went to bed last night I stopped on the upstairs landing, my head spinning with the realisation that the world stood on the edge of an abyss, with two nuclear powers potentially at war before too long.

I paused at the threshold of each of my children’s bedrooms, listening to them breathe easily as they slept peacefully, the sort of thing I had not done for some years as they are teenagers now. Lodged in my mind was something a British politician said almost 56 years ago, which was before I was even born.

In late October 1962, as the Cuban Missile Crisis finally cooled, Labour MP Frank Allaun got to his feet during a Parliamentary debate on what had just happened in Caribbean – when the world had seemed to be on the verge of nuclear conflict – and revealed how it had shaken him to his core.

‘I went upstairs and looked at my children, who were asleep, and wondered what kind of future, if any, they were going to have,’ Allaun told his fellow MPs. ‘I guess that parents throughout the world had the same sort of reaction. I have maintained for some years that mankind’s chances of survival are only fifty-fifty. In the light of the last few days, however, I would say that the odds have considerably worsened.’

I could never have guessed when I found those words in Hansard while researching and writing my book ‘Hunter Killers’ , about British submariners versus the Soviets in the Cold War, that just five years after it was first published I would be having similar thoughts.

Thankfully, the dawn broke without the world having been obliterated by nuclear weapons and the breakfast news programmes continued their discussions with politicians and top brass about the mechanics of the Syrian crisis. An air of unreality still hung over it all, as if it was all some kind of outlandish computer game.

Yet, just as with the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, today naval forces are being positioned to face each other down, armed to the teeth and potentially on a hair trigger with the horrifying spectre of nuclear exchange looming darkly over all of us.

A Soviet submarine caught on the surface during the Cuban Missile Crisis of late 1962. Photo: US Navy/US National Archives.

That we are here is doubly bewildering for me, as I witnessed the end of the Cold War at sea between NATO and Soviet naval forces. In the aftermath of the hardliners coup of August 1991, I sailed into the Barents Sea as an embedded journalist aboard the anti-submarine and intelligence-gathering frigate HMS London. As recounted in another book of mine, on the fighting lives of frigates named HMS London, back then there had been real fears that Gorbachev would fall and that the communist hardliners would return us all to the East-West confrontation.

HMS London had been sent into the High North on a long-planned diplomatic mission to make visits to Murmansk and Archangel even as the attempted coup unfolded and collapsed. What kind of reception would the Russians give to HMS London? She had already been overflown by Soviet jet bombers and was being shadowed by a sinister-looking Russian destroyer. With chaos in Moscow, nobody knew if the old foe was setting his face into stone again for a renewal of the confrontation, or would be welcoming.

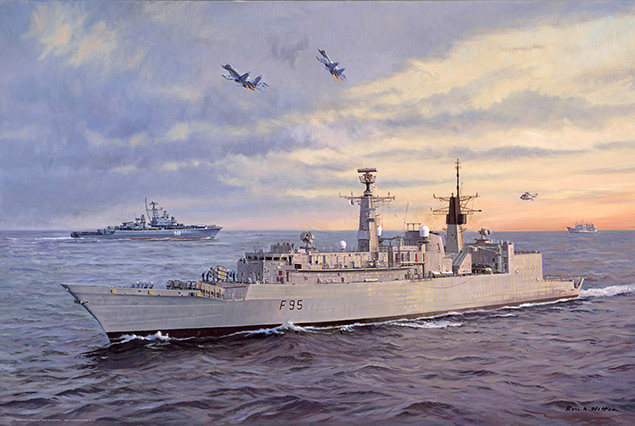

A depiction of the end of the Cold War between the Royal Navy and Soviet Navy in the Barents, with the frigate HMS London greeted in the old battleground by the Soviet Navy warship Gromky and two Sukhoi fighter jets of the Russian naval air arm. Painting by Ross Watton © 2013. For more on the work of Ross Watton visit www.rosswatton.com

‘As HMS London sailed out of a brilliant orange sunset in the west, the Soviet Navy frigate Gromky suddenly plunged out of the steel grey curtain of drizzle and gloom that had fallen in the East,’ observe my diary notes from the 1991 voyage. ‘She closed in spectacular fashion – at her top speed…prow plunging into the sea, ploughing a furious furrow of spray. The crew of HMS London, who were told to clear lower decks, gave her a rousing welcome, cheering “hurray! hurray! hurray!” and lifting their caps in salute. The Gromky’s crew replied in similar fashion and with great gusto. Then all eyes switched skywards as two Soviet naval air arm SU-27 Flanker fighters wheeled low overhead with a bunsen burner roar. They dipped their wings in salute before their pilots pulled back hard on their control columns, showing off what fantastic technology the Soviets could produce to the old enemy… taking their jets up in a spectacular climb above the British frigate.

‘Soon HMS London was cloaked in black, red and grey smoke, created by Soviet naval vessels only faintly made out in the gathering night. Flares dropped from low flying Mail anti-submarine flying boats and May maritime patrol aircraft created more smoke. When the smoke screens dispersed London found herself passing the Soviet Navy hospital ship Svir, which was carrying more than 100 British and Russian veterans of the [WW2] Arctic convoys. The cheering veterans welcomed HMS London to the fold, shouting and waving from the guardrails of the Svir’s packed upper decks.’

That just over quarter century later we have moved to a situation where British submarines could soon potentially launch cruise missiles into Syria, and then be hunted and come under attack from Russian warships in the eastern Mediterranean, is, to say the least, a deeply sad turn of events.

The Royal Navy hunter-killer submarine HMS Trenchant surfaces in the Beaufort Sea during a joint UK-US exercise last month (March). Armed with Tomhawak missiles she may be one of the units Britain sends into action against Syria. Photo: US Navy.

Those of us who witnessed the thawing of the Cold War in the Barents – the most dangerous front line at sea – breathed a deep sigh of relief that 40 years of knife-edge confrontation, with the threat of nuclear Armageddon hanging over humanity, was finally over.

In the warm glow of that long confrontation finally being over, we could never have imagined that the world would slide back into the era of nuclear war threats being hurled around, or the repeated use of chemical weapons on civilians.

Yet here we are with the very real possibility of the naval forces of the West and Russia on the brink of the kind of hot war that never actually happened during the Cold War between those two sides. In 1962 cool heads prevailed despite the readiness of Soviet forces on Cuba to fire their nuclear-tipped missiles and the Americans pursuing and forcing Russian submarines to surface.

Indeed, who could have guessed even four years ago when I embarked on writing my latest book, ‘The Deadly Trade’, that an American President would use social media to explicitly threaten the Russians with missile attack.

The Ohio Class guided-missile submarine USS Florida departs Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay. Capable of launching up to 154 Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAM) the Florida is most likely still deployed and may be ordered to bombard chemical weapons targets in Syria. Photo: US Navy.

But, it was the Russians who unwisely provoked him in the first place by threatening direct assault on American forces launching any missiles into Syria. In the recent past, as recounted in ‘The Deadly Trade’, the Russians have even threatened European naval forces with nuclear attack as retaliation for their governments daring to consider arming frigates and destroyers with Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) systems.

Threats of nuclear annihilation by Moscow are nothing new. In the summer of 2014, not long after his forces annexed the Crimea and began fuelling insurrection in eastern Ukraine – the opening shots against the West for pushing too far east with NATO among other so-called transgressions against Russia – President Vladimir Putin stated that his country was reinforcing its ‘powers of nuclear restraint’. He added that other nations should ‘always realise that is it better not to mess with Russia.’

The new Russian guided-missile frigate Admiral Essen, which is reportedly in the eastern Mediterranean awaiting orders from the Kremlin. Photo: Cem Devrim Yaylali. For more of his work visit: www.turkishnavy.net

What made the situation this spring much worse was the reaction of the US President, who stoked the fires with the notorious tweet in which he warned: ‘Russia vows to shoot down any and all missiles fired at Syria. Get ready Russia, because they will be coming, nice and new and “smart!”.’ Trump later tried to be more conciliatory but the world is less likely to remember his emollient tweet about helping with the Russian economy and avoiding an arms race.

As I suggest in ‘The Deadly Trade’, in an era of strongmen puffing their chests out and making blood-curdling threats to inflict mass destruction on would be foes, humanity will have to rely on what President Abraham Lincoln, during his inaugural address of March 1861, called ‘the better angels of our nature’. They prevailed during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and we must pray they do so again today as the submarines and surface warships of both sides position themselves in the eastern Mediterranean.

Iain Ballantyne is the Editor of the global naval news magazine WARSHIPS International Fleet Review and author of the recently published ‘THE DEADLY TRADE: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’ (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25.00, hardback).

Iain Ballantyne is the Editor of the global naval news magazine WARSHIPS International Fleet Review and author of the recently published ‘THE DEADLY TRADE: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’ (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25.00, hardback).

‘THE DEADLY TRADE: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’ is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on (752 pages, hardback £25.00/eBook £12.99).

‘THE DEADLY TRADE: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’ is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on (752 pages, hardback £25.00/eBook £12.99).