Cold War Diesel Submarines: The Unsung Heroes

One of the submarines that features in the narrative of ‘Hunter Killers’ is the Cold War veteran diesel-electric submarine HMS Alliance, which is splendidly preserved at Gosport in Hampshire as the star attraction of the Royal Navy Submarine Museum (RNSM). Alliance is big news in 2014 as she has just completed a major a £6.75 million refurbishment. An Alliance Gallery has also been constructed within the main museum building. The gallery’s aim is to immerse people in the story of Alliance from Second World War origins to her finals days of service in the 1970s (as a complement to the guided tours of the boat herself). HMS Alliance is living proof of an important side of the Cold War under the waves that is often overlooked in favour of the headlines-grabbing exploits of the nuclear-powered SSNs and SSBNs, namely the valiant efforts of the diesels across the span of the confrontation. Published here is an article that I wrote for the current (April 2014) edition of ‘Scuttlebutt’, the official magazine of the Friends of the Royal Naval Museum (Portsmouth) and HMS Victory. The piece seeks to cast a light on the adventures of British diesels of all kinds in the Cold War, drawing on elements of ‘Hunter Killers’.

If Hollywood movies and blockbuster novels are to be taken as gospel the Cold War under the sea was an affair of big beasts known as nuclear-powered submarines jousting with each other at close quarters.

This overlooks the valiant efforts of the smaller, far less powerful but equally hard-worked, diesel-electric submarines. Out of the three primary players in the undersea contest – the USA, Soviet Union and Britain – it was the British who most relied on diesels to do dangerous work the other two nations handed over to nuclear-powered boats.

The three navies began the Cold War from the same place – using captured Nazi vessels as the basis for regenerating post-WW2 submarine flotillas. They could thank British commandos for this. In the dying days of the Third Reich teams of elite green berets raced for Baltic ports where they secured revolutionary undersea craft and associated technology.

Among around 100 former Kriegsmarine submarines interned at Lishally, near Londonderry, were Type XXI U-boats. Fortunately, only two ‘electroboots’, as the Type XXIs were known, had ever deployed on combat patrol. Training crews, ironing out defects common to cutting-edge technology and intensive Allied bombing ensured the rest of Germany’s 120 ‘electroboots’ remained in port.

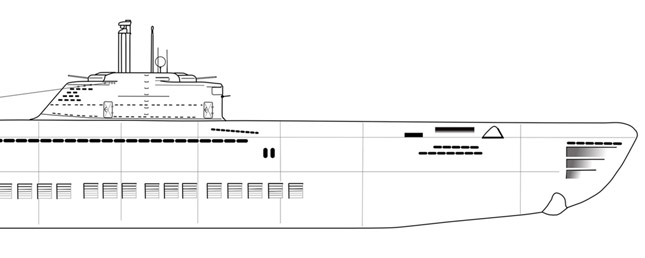

The Nazi-origin Type XXI U-boat, which provided the technological basis for early Cold War submarines used by the British, American and Russian navies. Image: Dennis Andrews. Copyright © Dennis Andrews.

Equipped with high-speed batteries capable of providing up to 17 knots submerged – eight knots faster than Allied diesels – the Type XXI possessed snort masts enabling it to remain submerged for long periods. It was invisible to the enemy while venting generator fumes, recharging batteries and sucking in fresh air. With its sleek, supremely hydrodynamic hull form, the Type XXI also looked very different to other submarines, with no external guns other than cannons mounted within the fin.

The Type XXI did not have to surface to attack a convoy and could fire 18 torpedoes (in three salvoes) within 20 minutes. This was as long as it took any other submarine to load a single torpedo. Using the snort to recharge batteries, the Type XXI was supposed to conduct an entire patrol submerged. Stealth at low speeds was aided by creeping speed motors (on rubber mountings) that soaked up noise. The Type XXI was also deep diving, managing up to 440ft (around 90ft deeper than the most British submarines of the 1940s). It reputedly had a crush depth of more than 1,000ft.

When it came time to dividing up the spoils of war, the victorious powers were keen to ensure they got their share of Nazi submarines. The British, Americans and Russians each had ten U-boats of all kinds. The remainder were towed out to sea and scuttled off Ireland.

The Americans used their two Type XXIs as the basis of new Tang Class diesels, also reconstructing some of their Second World War-era boats under the Greater Underwater Propulsive Power, or GUPPY, programme to incorporate German innovations. Some Type XXIs were even pressed into service, the British operating two for a short period while the Russians, who had been awarded four Type XXIs, commissioned them into service with their Baltic Fleet. The Soviet Navy replicated the Type XXI in its Zulu and Whiskey classes. Without the funds to construct new boats, the British decided to incorporate Type XXI innovations into some of their T-Class submarines.

Eight boats, starting with HMS Taciturn, were taken in hand between 1950 and 1956. They had a whole new section inserted containing two more electric motors and a fourth battery. It gave the Super-Ts, as they became known, a submerged top speed of up to 18 knots but only for a short period. The guns were removed and they also acquired a streamlined casing. A large fin enclosed the bridge, periscopes and masts. Space was also made internally for specialist intelligence-gathering equipment.

Alongside the Super-Ts the Royal Navy continued to operate other Second World War-era diesels, some of which also eventually received similar design improvements, such as the A-Class.

The Submarine Service’s main effort against the Soviets in northern waters during the late 1950s saw the Super-Ts and their crews carrying the burden and taking plenty of risks. They endured marathon deployments during which both men and submarines were pushed to the limit.

In the late 1950s, Lieutenant Commander Alfie Roake, a veteran of the Arctic convoy runs during the Second World War, was appointed captain of HMS Turpin. One deployment under Roake’s command saw Turpin’s hatch shut on Trafalgar Day 1959 and not opened again for another 39 days, the boat spending most of her time carefully husbanding water and air while evading the Soviets in Arctic waters.

Roake said he felt like ‘David against Goliath, in my small diminutive “T” boat of some 1,320 tons carrying out a tiny pin prick of an operation against a colossus. We were on our own with the nearest support and succour thousands of miles away.’

On a subsequent foray into the Russian Bear’s backyard, a Soviet submarine Turpin was recording and photographing suddenly dived right on top of her. The British boat dodged quickly out of the way. Later the sound of what may have been depth charges detonating was picked up. Roake also feared the Soviets had fired torpedoes at Turpin, issuing orders for the submarine to go deep and turn in order to comb possible tracks.

On returning to Gosport from such missions the diesels got no recognition at all – senior officers Roake reported to declined to even acknowledge where he had been or what his boat had been doing. Roake observed rather drily: ‘We flew no “Jolly Roger” listing our achievements and had no special welcoming party – we left and entered harbour like “a thief in the night” … We had no feed-back as to how we had done, and a verbal enquiry elicited a non-committal reply … Meanwhile, we were all ordered not to breathe a word about our adventures …’

The Royal Navy’s remodelled A-Class boats were in the early 1960s drawn into the Cuban Missile Crisis, British naval participation in this dangerous episode going largely unrecognized (if at all).

As Prime Minister Harold Macmillan got up in the House of Commons during those dangerous October 1962 days, to explain what Britain’s response was, there was no mention of the part played by Royal Navy submarines operating from Canada and even deploying on war patrol from Scotland.

Both HMS Astute and HMS Alderney were ordered to sea from their home base at Halifax, Nova Scotia, to join a picket line attempting to detect Soviet submarines heading south for Cuba, trailing them if possible and marking them for potential destruction.

The crews of the Halifax-based submarines were Anglo-Canadian. They received instructions from the senior Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) admiral who had ordered them on picket duty that had a decidedly chilling effect. The Canadian national government was opposed to military action to resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis.

However, in the event of hostilities there would be no time for RCN submariners to be taken off the British submarines when they reverted to UK national control for combat. Therefore, in the event of war, the Canadians would stay with their shipmates. The admiral order that they must ensure they were not captured with ‘CANADA’ shoulder flashes still on their uniforms. Nor could they even be caught dead with them. They must cut the shoulder flashes off.

Meanwhile, among the boats sent out from Faslane on war patrol was HMS Auriga, which was already preparing for a tour of duty based in Halifax. Her work-up off the west coast of Scotland was interrupted by a FLASH message telling her to return home immediately and store for war. Lieutenant Rob Forsyth thought it was all very exciting. Only recently promoted, his new responsibilities included being the boat’s Assistant Torpedo Officer.

The British diesel submarine HMS Auriga noses through ice in Arctic waters in the early 1960s, while operating out of Canada. Photo: Forsyth Collection. © Rob Forsyth.

Leading Seaman John Cumberpatch, the experienced rating who really ran things, assured Forsyth everything would be fine as they offloaded dummy fish and took aboard torpedoes with warheads.

Once deployed on picket duty, Auriga made several contacts – Soviet submarines heading south at speed and soon out of range. In the end, while the British submarines pulled extended war patrols they did not find themselves involved in a hot war.

Soon Auriga was herself operating out of Halifax, conducting training missions that surely tested everybody’s nerve to breaking point. She ventured under ice in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to simulate lurking Soviet submarines. In that role she was hunted by nuclear-powered US Navy attack submarines keen to hone under-ice tactics. It was a risky job.

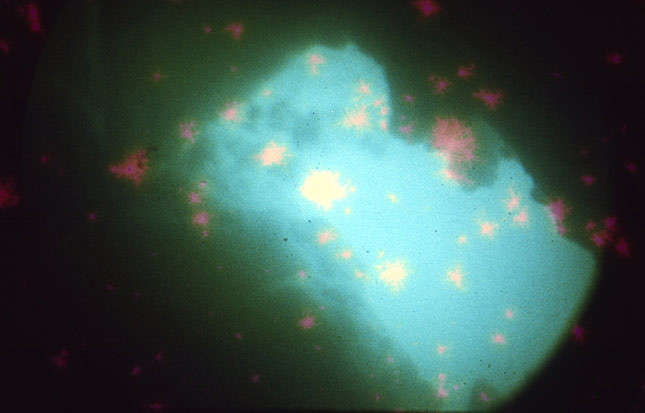

The mere thought of a fire under the ice sends a shudder through any submariner, especially if combined with battery life seeping away as a diesel boat tries repeatedly, and fails, to smash through. Not only will you have a fire consuming all the oxygen, but also your crew will be fighting for breath as the submarine fills with noxious fumes. There is no means of escape and each time you try to break through your battery gets weaker, death that bit closer. Flood is also a desperate prospect. Should a boat spring a leak she’ll swiftly fill up with water, drowning her occupants or freezing them to death.

The pressure will squeeze more and more water into the submarine until the craft sinks like a stone. To the forefront of everybody’s minds as Auriga slid under the ice in 1962/63 was, of course, a desire for the boat to have a polynya – an area of open water – nearby at all times. Auriga endeavoured to be no more than half an hour from one.

Polynya as viewed via the periscope of HMS Auriga, while the British diesel submarine is dived under Arctic ice in the early 1960s during the Cold War. Photo: Forsyth Collection. © Rob Forsyth.

Between the end of the 1950s and late 1960s, the Royal Navy produced the excellent Porpoise and Oberon classes of diesel boats, with the Super-Ts and the modified A-Class increasingly obsolete and phased out. The British diesels would carry on shouldering the burden of the main undersea effort against the Soviets well into the 1960s, but it was their last period at the tip of the spear.

HMS Alliance – commanded by the aforementioned Rob Forsyth in 1970/71 – was not taken out of the front line fleet until 1973 (and she serves on today of course, as the star exhibit of the Royal Navy Submarine Museum).

New nuclear-powered Fleet boats (SSNs, also known as hunter-killers) would increasingly take the lead role in long-range surveillance and Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) operations. The diesels would still be used for close inshore surveillance, on training task and Special Boat Service (SBS) insertions, plus patrols in waters close to the UK. They would also go into shallow Scandinavian waters and conduct barrier patrols in the crucial Greenland-Iceland-UK-gap (GIUK).

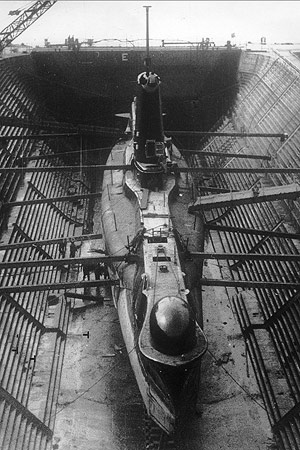

HMS Alliance in dry dock at Devonport in the early 1960s. Photo: Crown Copyright/Royal Navy.

Meanwhile, some of the future nuclear submarine captains of the 1980s found themselves serving in the diesels during the 1970s, gaining valuable experience.Once such was Doug Littlejohns whose first command in the mid-1970s was the Oberon Class submarine HMS Osiris. He took her up against interfering Soviet spy vessels in waters off Dorset and Scotland and then into the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean on surveillance missions. It all required the customary grit, endurance and derring-do of traditional diesel boat operations. Both Forsyth and Littlejohns would also command the nuclear-powered Sceptre. Another graduate of the diesels, Dan Conley (who later commanded Courageous and Valiant, both SSNs) experienced the final days of gracious colonial submarining during the early 1970s. As a junior officer in HMS Oberon, he made flag flying visits to exotic ports – including Colombo, Penang, Hong Kong, Bangkok and Manila. The primary threat was to his liver, from too many gin slings, though earlier generations of Far East submariners had in the 1960s conducted surveillance and commando insertion missions during the confrontation with Indonesia.

With the sun finally setting on the surviving outposts of empire, Oberon was the last British submarine to be deployed for operations from Singapore. Conley found Oberon to be ‘absolutely pristine, well managed and well crewed – generally a happy boat and overall very professional.’

Returning to the UK, Conley and the Submarine Service forever left behind dinners of Lobster Thermidor and cold beer in the Officers’ Club and, as he put it, ‘knuckled down to the real Cold War business after our time in the sun.’

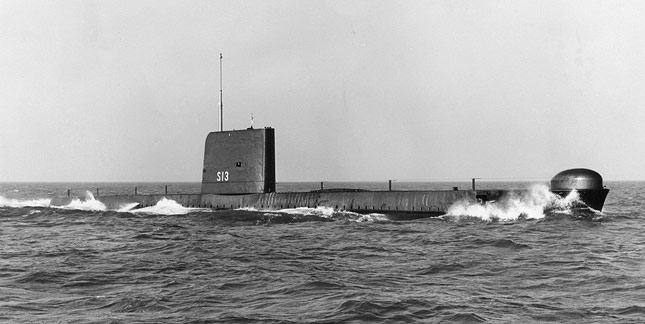

HMS Osiris, an Oberon Class diesel submarine of the Royal Navy. Photo: BAE Systems.

The diesels would, though, twice be drawn away from their Cold War patrol areas to engage in daring hot war operations. Onyx conducted a marathon 116-day patrol to the Falklands in 1982, unsupported 8,000 miles from the UK under the command of Lieutenant Commander A.P. Johnson. Though Lt Cdr Johnson has never commented on his submarine’s mission, it is believed she landed SBS troops on various raids. Her captain drew on periscope and shallow water navigation skills he had learned during the notoriously demanding Perisher submarine command course. They did not fail him, or his crew. On her return to Gosport, every ship in Portsmouth Harbour sounded sirens and hundreds of sailors cheered the tired old Onyx home.

The last of the Royal Navy’s O-boats was retired in 1993, though there had been a final opportunity to show their worth during the 1991 Gulf War. Opossum and Otus carried out covert operations not dissimilar from their reputed activities in the Baltic against the Soviets. Their presence in either the Baltic or the Gulf during early 1991 has never been officially confirmed by the Ministry of Defence (MoD).

It has been claimed that during coalition efforts to evict Iraqi occupiers from Kuwait the O-boats landed SBS reconnaissance teams on the coast to scout out enemy defences. In one incident US Navy strike jets allegedly sank an oil tanker, which began to sink on an O-boat hiding underneath while attempting to recover a Special Forces team. She swiftly withdrew.

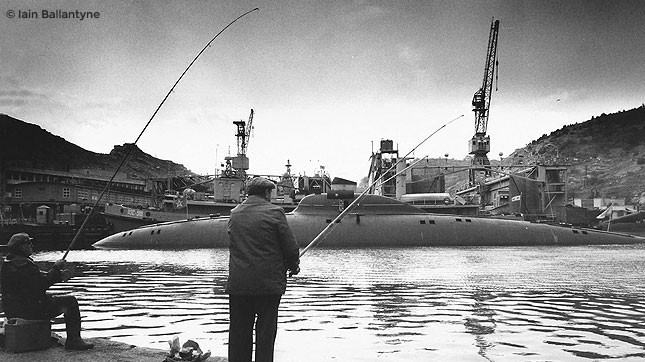

HMS Alliance at Gibraltar in the early 1970s during the time Rob Forsyth was in command. Photo: Rob Forsyth Collection.

In the early 1990s HMS Dolphin ceased to be a submarine base. The four Upholder Class diesels that had been commissioned to replace the O-boats switched to Devonport. For Britain, with its Submarine Service shrinking dramatically in post-Cold War defence spending cuts, a decision was then made to go all-nuclear. The Upholders were paid off in the mid-1990s and later sold to Canada, where they continue to serve.

Gazing back across the decades of the Cold War, and weighing up the exploits of the diesels and how they produced the men who became warrior scientists in nuclear-powered boats, it’s worth considering what was fundamental to success (and survival).

Tim Hale came up through the hard school of the diesels. He commanded several conventional boats, including Tiptoe (a Super-T), and was XO of Warspite in the late 1960s. He also commanded Swiftsure, first of a new breed of SSNs, bringing her out of the builders and into service during the early 1970s. He points out that good seamanship is absolutely essential to successful operations in any submarine, which, he rightly points out, ‘operates in three dimensions.’ Hale adds: ‘If it goes to all stop, a surface ship will probably float. Not so in a submarine or aircraft. You have to keep the thing moving and put it on the interface of the fluids – water and air – in order to achieve stability. The need for awareness and competence is thus paramount in order to stay alive.’

In the diesels of the Cold War it also took a certain kind of luck and courage.

‘Hunter Killers’ by Iain Ballantyne is available in both hardback and ebook formats (£20.00) from various retailers or direct from Orion. The paperback edition will be published in August. The nuclear-powered boats on the cutting edge of the face-off with the Soviets feature heavily in ‘Hunter Killers’ but Rob Forsyth’s time in command of Alliance is detailed in one chapter while the exploits of several other diesels are covered across the book, from the 1950s to the early 1990s.

For more about HMS Alliance visit the RNSM web site.

Find out more about the Friends of the Royal Navy Museum and HMS Victory here.