Cold War Under the Sea: Where Fact Blends With Fiction

An academic reviewing ‘Hunter Killers’ remarked that it shows how sometimes ‘Cold War fiction and Cold War fact blend seamlessly at the edges’. And he’s right, for the Cold War often threw up strange episodes that inspired Hollywood and novelists to create a kind of faction.

For example, Alistair MacLean – who served in the Royal Navy on the Arctic convoys during WW2 – based elements of his 1963 novel ‘Ice Station Zebra’ on real-life events. These included the 1959 loss of a film container from an American intelligence-gathering satellite over the Arctic. The Soviets were said to have recovered it along with whatever secrets it contained.

In May 1962 the CIA parachuted operatives onto pack ice near an abandoned Russian ‘research station’. It was really a listening post for detecting US Navy nuclear-powered submarines. The CIA men collected valuable intelligence material and were then plucked off the ice in breath-taking fashion by a specially converted B-17 bomber that reeled them in.

In ‘Ice Station Zebra’ a British rescue station in the Arctic is the scene of espionage skullduggery and is set on fire, with a US Navy nuclear-powered submarine sent under the Polar ice to carry out a rescue mission. In the novel and 1968 movie of the same name the American vessel also goes to try and recover a film canister containing spy satellite imagery.

A UK-made movie called ‘The Bedford Incident’, released in October 1965 and starring Sidney Poitier and Richard Widmark, depicted the pursuit of a Russian diesel submarine in waters off Greenland.

The Soviet boat is kept down until her air has almost run out and launches a nuclear-tipped torpedo when the destroyer USS Bedford accidentally fires anti-submarine rockets.

Not long after an eerily similar episode occurred in British waters, in my book dubbed ‘The Kosygin Incident’. At 10.30 a.m. on 6 February 1967 – the same day Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin’s airliner touched down on British soil for an official visit – a Shackleton maritime patrol aircraft of the RAF picked up a contact about 100 nautical miles to the north-west of Malin Head. Having already dropped a string of sonar buoys as part of a major Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) exercise with the Royal Navy, the aircraft was able to classify it as ‘probably a submarine’.

Frigates, diesel submarines and the nuclear-powered submarine HMS Dreadnought were soon ordered by a senior admiral to ‘close the [suspected Soviet] submarine’s position for the purpose of hunting her’.

As news of this inconvenient incident reached government circles alarm bells rang and the hounds were called away from their quarry (identified as a Whisky Class diesel that departed the Baltic on January 22). Fortunately reality had not mirrored the catastrophic conclusion of ‘The Bedford Incident’.

The archetypal example of Cold War submarine faction was Tom Clancy’s ‘Hunt for Red October’. This was partly the fruit of the late novelist’s trawling for nuggets of fact to inform his fiction while visiting American naval officers to sell them insurance (his job before he broke through as a writer).

Hollywood fiction: Sean Connery as Capt. Marko Ramius in the movie version of Tom Clancy’s ‘The Hunt for Red October’. Image: Paramount.

Doug Littlejohns – captain of several British submarines during the Cold War and one of the key players in the ‘Hunter Killers’ narrative – got to know the American blockbuster master.

As related in ‘Hunter Killers’, during a trip to the States in the mid-1980s a fellow British submarine officer gave Littlejohns a copy of ‘Hunt for Red October’ to read. Littlejohns consumed it overnight and decided he had to meet Clancy. When they met Littlejohns told Clancy: ‘You’ve put stuff in your book that if I talked about it would see me locked up in the Tower of London.’

The two men became friends, though Littlejohns had to keep a professional distance while still a serving naval officer. Clancy was inspired enough to pay tribute to Littlejohns by basing a character in ‘Red Storm Rising’ (the follow up to ‘Hunt for Red October’) on the British submarine captain. After Littlejohns retired from the Navy he co-founded Red Storm Entertainment with Clancy, specialising in video games.

Nobody should underestimate the impact of Clancy’s Cold War thrillers, which while not works of high literature, offered excitement and also insight into a previously secret world.

The Hollywood movie based on Clancy’s novel, starring Sean Connery and Alec Baldwin, was a major success despite being released after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Its powerful imagery and exciting depiction of life beneath the waves still had pulling power. A few years ago I met a young naval officer who responded, when asked what had inspired him to join the Navy and become a submariner: ‘A movie called The Hunt for Red October.’

Hollywood fiction : A scene from the movie version of Tom Clancy’s ‘Hunt for Red October’. Image: Paramount.

Someone told me recently that they hoped I would not be insulted by the compliment that ‘Hunter Killers’ reads like a thriller. On the contrary, that is the point – to take people inside the Cold War and show them how exciting and dangerous it really was by, where appropriate, using techniques more traditionally employed by the novelist.

Therefore in ‘Hunter Killers’ we have chapters featuring nerve-wracking rides down undersea canyons, dangerous games of chicken and the long distance hunt for the Russian carrier Kiev across the Mediterranean by HMS Sceptre (in the late 1970s the British SSN was commanded by Rob Forsyth, another major player in the book’s narrative).

A chapter on CIA analysts trying to sort out the fact from fiction of a rumoured new Soviet super submarine (a chapter called ‘The Alfa Enigma’) of course rings bells of similarity with some Cold War fiction.

In ‘The Hunt for Red October’ for instance CIA analyst Jack Ryan tries to get to the bottom of the Soviet Navy submarine Red October’s radical new propulsion. In real life it took years for the CIA’s analysts to persuade the Pentagon the Soviets really had built a super fast, deep diving nuclear-powered submarine (with revolutionary liquid metal reactors). It was called the Alfa by NATO and represented a quantum leap in capability that the West did not want to believe the Russians could achieve.

The reality of ‘Hunter Killers’ matches and betters fiction: Soviets depth charging and trying to ram British submarines off Russia; Royal Navy SSNs colliding with Russian submarines and nearly being sunk (incidents which even today, decades later, the MoD insists were bumps with icebergs); Soviet spy ships attempting to run down one of the UK’s Polaris missile submarines and almost sinking a RN diesel submarine just off the British coast.

And there’s much more besides, not least daring up close espionage, with periscopes just inches away from whirling Soviet surface ship propellers and tricky explorations of sun-kissed foreign anchorages in clear visibility waters (with big black submarines dodging nimbly around anchor cables).

In the end ‘Hunter Killers’ is not a tale of big boys and their toys doing daring things for fun, but a deep dive into a nightmarish period of world history.

The warrior-scientists in their submarines waged a covert, silent war with utter dedication. They were handpicked for mental strength and agility, plus their nerves of steel ability to make the right life-or-death decisions when nuclear-powered, and armed, submarines were sliding by within feet of each other.

Some people with the benefit of hindsight perhaps might regard the undersea confrontation of the 1950s – 1990s as an exercise in futility. All that money poured into all that technology, all that intellect applied to creating vessels of war that could snuff out all life on the planet – yet a war without battles that has faded into the deep dark ocean of legend as if it never was.

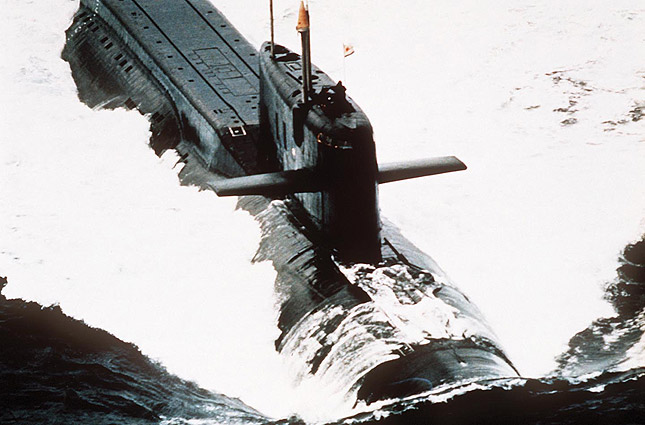

Submarine reality (below): A US Navy attack submarine surfaced through the Arctic ice pack. Photo: US Navy.

But that’s the point. In maintaining the undersea rivalry at such fever pitch, waging it with such dedication and enduring so much hardship to do so, submariners on both sides ensured politicians had to always calculate that it was never worth taking the gamble on waging conventional war in Europe.

In that way the submariners could be said to have saved millions of lives by preventing a re-run of errors committed in WW1 and WW2 when kings and politicians started conflicts that they could not stop without huge blood-letting, social anarchy and wasted treasure.

During the Cold War the leaders of both East and West knew that to begin a hot war would surely end in the deaths of everybody. The submariners had no desire for the shooting to start, or as Doug Littlejohns puts it: ‘ We don’t want to make war – submariners are among the people that least want to make war.’

In Hollywood movies and pulp fiction the protagonists invariably resort to violence as a means to resolve their conflicts. The aim of the Cold War submariner was to threaten the use of force but to never use it, for to do so would represent failure.

The fact that such lethal beasts as submarines were ultimately weapons for peace was surely the greatest plot twist – and the most fascinating paradox – of them all.