On 12 October 1939, a Luftwaffe reconnaissance flight confirmed the Home Fleet of the Royal Navy was in Scapa Flow and ripe for attack. The Germans had previously spotted a gap in the sea defences of the RN’s main war base and so kept a keen eye on things there.

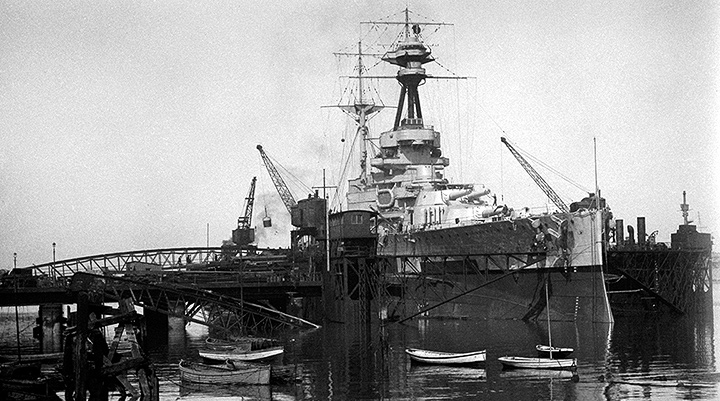

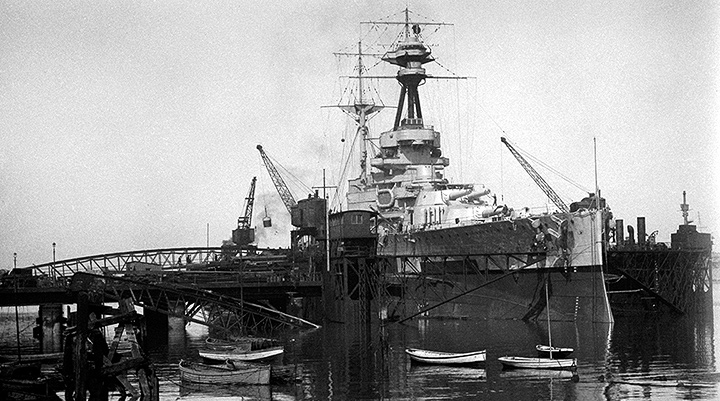

The British war anchorage at Scapa Flow, at the end of WW1, with the interned German battle fleet enclosed. Photo: NHHC.

After sunset, however, the majority of the British vessels departed, with battleship Rodney and rest of the fleet heading for Loch Ewe on the west coast of Scotland. Yet the battleship HMS Royal Oak, which had been detached to patrol waters between the Orkneys and Shetland, remained at Scapa. Her job was also to act as anti-aircraft guardship for Kirkwall.

U-47, under the command of Kapitanleutnant Gunther Prien, had been sent to exploit Scapa’s defensive vulnerability and achieve something his forebears during WW1 had failed to do – sink a British battleship in the anchorage. As he took his boat north, Prien followed a pattern or running that aimed to ensure maximum stealth and survivability. U-boats, like all diesel-electric submarines, were much faster on the surface than dived.

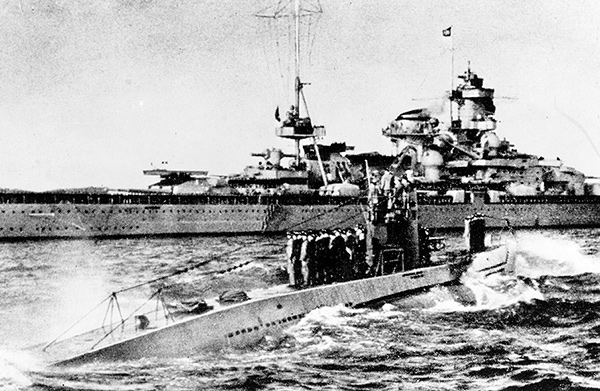

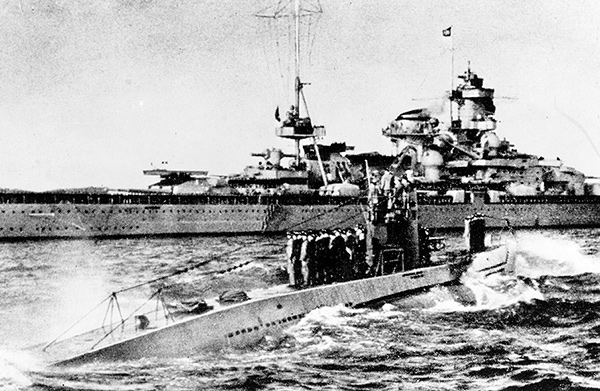

The famous German submarine U-47 departing on patrol in 1939. Photo: US Naval History and Heritage (NHHC).

However, in seas where the enemy had dominant air cover – and with plenty of British patrol vessels also present – it was madness to try and cruise on the surface in daylight. Therefore, U-47 stayed submerged and rested on the seabed during the day, keeping the draw on battery power to a minimum. Most of U-47’s men got some sleep. After dark the boat surfaced and made speed towards Orkneys, her diesels driving hard – the batteries recharging and the engine fumes venting from the boat.

Prien had volunteered for the mission after being asked by Donitz, if he thought he could handle it. Had he refused, so Donitz maintained, there would be no stain on his record, but the ambitious Prien did not shirk the task. In WW1 the boats U-18 and UB-116 had been sent to penetrate Scapa, but had themselves been destroyed. Could Prien pull it off in the new war with Britain, his tiny craft delivering a devastating blow against the goliath of the seas that was the Royal Navy?

Until October 13 the crew of U-47 did not know exactly what their mission was about, though they guessed something big was imminent. When Prien gathered them in the forward torpedo room to reveal their objective, his men seemed to accept it with equanimity. The silence as they contemplated the enormity of the undertaking was broken only by ‘a soft gentle crunching sound as the boat shifted on the sea bed,’ as one account of the moment later described it.

U-47 rested on the bottom all that day, the boat surfacing at 7.15pm, when a hot meal was served – roast ribs of salt pork with cabbage. Making speed on the surface, there was a heart-stopping moment at 11.07 pm when the black mass of a ship materialised out of the night. It was only a merchant vessel, but Prien still dived U-47, to guarantee slipping by unobserved. When the U-boat again surfaced, Kirk Sound was visible ahead and Prien was presented with what he described in his patrol report as ‘a very eerie sight.’

In WW2 U-47 would penetrate Scapa Flow to attack Royal Navy warships and sink HMS Royal Oak (seen above in a floating dock between the wars). Photo: AJAX Vintage Picture Library.

He added: ‘On land everything is dark, high in the sky are the flickering Northern Lights, so that the bay, surrounded by English [sic] mountains, is directly lit up from above. The blockships lie in the sound, ghostly as the wings of a theatre.’ Deciding to squeeze past those blockships on their northern side, from the bridge of his boat Prien spotted the big, bulky silhouettes of ‘two battleships’ along with seemed to be destroyers lying beyond.

At 12.58am, with just 22ft below the boat’s keel, Prien fired one torpedo at what he referred to as ‘the northern’ ship and two at ‘the southern.’ All had impact exploders. ‘After a good three minutes, a torpedo detonates on the northern ship,’ reported Prien, ‘of the other two nothing is to be seen.’

Disappointed, but with no interference so far from the enemy, Prien swung U-47 around and launched a torpedo from the stern tube. He then turned the boat to fire three more torpedoes from the bow tubes, some with magnetic exploders. ‘There is a loud explosion, roar, and rumbling,’ recorded Prien of what happened next. ‘Then come columns of water, followed by columns of fire, and splinters fly through the air. The harbour springs to life…A battleship has been sunk, a second damaged…All the tubes are empty. I decide to withdraw…’

U-47 made off at high speed – still on the surface – exiting Scapa by Skildaenoy Point. Breaking through into the open sea, U-47 went as fast as she could, heading south-east and for home. With daylight fast approaching, Prien decided U-47 would be best advised to dive and sit on the seabed for a few hours to let the fuss die down. As he left the bridge Prien took a last look over his shoulder: ‘The glow from Scapa is still visible… Apparently they are still dropping depth charges.’

A few weeks after sinking the Royal Oak, U-47 sails back into Kiel with her crew arranged on her casing. The battle-cruiser Scharnhorst is in the background. Photo: US Navy/NHHC.

On October 15, Prien sent a signal to U-boat headquarters: ‘Operation successfully completed. “ROYAL OAK” sunk. “REPULSE” damaged.’ He was not quite accurate – Repulse was not there – but he had put three torpedoes into Royal Oak, the old British battleship turning turtle and taking 800 men with her, devastating the families and loved ones of those lost.

Winston Churchill observed: ‘This episode, which must be regarded as a feat of arms on the part of the German U-boat commander, gave a shock to public opinion.’ It would be six months before Scapa Flow’s defensive gaps were plugged and the Home Fleet could return in safety to its principal war anchorage. Meanwhile, Prien and the crew of U-47 reached Wilhelmshaven on October 17 to be acclaimed national heroes. During an audience with Adolf Hitler in Berlin, U-47’s commander was presented with the Knight’s Cross. The Fuhrer hailed Prien’s achievement as ‘a unique triumph.’

Winston Churchill observed: ‘This episode, which must be regarded as a feat of arms on the part of the German U-boat commander, gave a shock to public opinion.’ It would be six months before Scapa Flow’s defensive gaps were plugged and the Home Fleet could return in safety to its principal war anchorage. Meanwhile, Prien and the crew of U-47 reached Wilhelmshaven on October 17 to be acclaimed national heroes. During an audience with Adolf Hitler in Berlin, U-47’s commander was presented with the Knight’s Cross. The Fuhrer hailed Prien’s achievement as ‘a unique triumph.’

More on the pursuit of submarine warfare in WW2 and other conflicts is to be found in Iain Ballantyne’s book ‘The Deadly Trade’ (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) It is published in the USA as ‘The Deadly Deep’ (Pegasus Books)

“This weekend I finished reading Iain Ballantyne’s book ‘Arnhem: Ten Days in The Cauldron’ and felt as if I had relived the entire battle again,” said Jan.

“This weekend I finished reading Iain Ballantyne’s book ‘Arnhem: Ten Days in The Cauldron’ and felt as if I had relived the entire battle again,” said Jan.

Winston Churchill observed: ‘This episode, which must be regarded as a feat of arms on the part of the German U-boat commander, gave a shock to public opinion.’ It would be six months before Scapa Flow’s defensive gaps were plugged and the Home Fleet could return in safety to its principal war anchorage. Meanwhile, Prien and the crew of U-47 reached Wilhelmshaven on October 17 to be acclaimed national heroes. During an audience with Adolf Hitler in Berlin, U-47’s commander was presented with the Knight’s Cross. The Fuhrer hailed Prien’s achievement as ‘a unique triumph.’

Winston Churchill observed: ‘This episode, which must be regarded as a feat of arms on the part of the German U-boat commander, gave a shock to public opinion.’ It would be six months before Scapa Flow’s defensive gaps were plugged and the Home Fleet could return in safety to its principal war anchorage. Meanwhile, Prien and the crew of U-47 reached Wilhelmshaven on October 17 to be acclaimed national heroes. During an audience with Adolf Hitler in Berlin, U-47’s commander was presented with the Knight’s Cross. The Fuhrer hailed Prien’s achievement as ‘a unique triumph.’