Convoy Battles were as Important as El Alamein, Stalingrad or Guadalcanal

Seventy-five years ago saw what has often been lauded as the moment of victory for the Allies in the Battle of the Atlantic. The key clashes were staged across April and May 1943, with convoy escorts battling a U-boat force encouraged by an impressive score in March – sinking 107 Allied ships in the month’s first 20 days – to believe it could yet secure supreme triumph for Germany.

As was so often the case in war, such an upswing in fortune could so easily become a downturn and signs of the German decline to come were there even in March. The month had closed amid dreadful weather, with only 15 enemy merchant vessels sent to the bottom by U-boats during its final 11 days. The submarine crews were tired, the boats battered and in need of repair, while fuel and torpedo stocks were depleted.

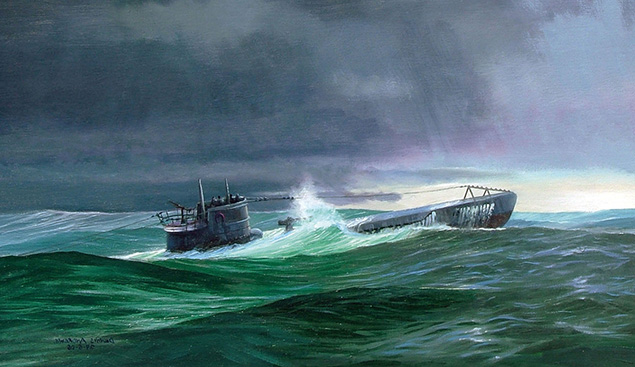

A U-boat hunts for a convoy in the vast N. Atlantic. Image: Dennis Andrews.

Yet the resilient U-boat force soon sent its submarines back into action, to become locked in battle with escort groups, trying to break through and attack merchant vessels.

The first of the pivotal fights came in early April with the assault on convoy HX-231, of 61 merchant vessels, a battle stretching across hundreds of miles of ocean. The cutting edge of the wolf pack was blunted above all by the determined actions of the B7 escort group, led by the Royal Navy’s formidable Commander Peter Gretton. Six merchant vessels were sunk, for no boats lost, but the overall performance of the German submarines had been timid, the U-boat force War Log blaming it on ‘the inexperience of young Commanding Officers.’

A British escort charges off to tackle a U-boat to prevent it from sinking merchant ships in convoy across the Atlantic. Image: Dennis Andrews.

In fact, morale was so fragile in the U-boat force that some submarine COs eagerly embraced any mechanical defect to report their vessels non-operational. Kriegsmarine commander-in-chief Grand Admiral Karl Donitz responded by threatening stiffer penalties for those he perceived to be shirkers.

The B7 group was also sent out to protect the 41-ship convoy ONS-5. The U-boats were ordered by their boss to wait for nightfall on 5 May and then to attack with vigour in order to ensure ‘there will be nothing of the convoy left’. This was far from being the case, with just 13 merchant vessels sunk, a poor return for five U-boats and their crews destroyed.

When the U-boats tried to score big again in late May, they failed utterly, with four submarines lost during attempts to attack convoy SC-130. All 37 of its precious merchant vessels – carrying fuel oil, explosives, lumber and grain among other things – were delivered safely to Liverpool.

By this time in the contest Allied escort groups & aircraft were clearly achieving a measure of superiority in the open ocean war that stacked the odds heavily against Germany’s submariners. In the first five months of 1943, Allied warships and aircraft sank 81 U-boats. With that rate of losses Donitz felt he had no choice but to admit wolf pack operations were no longer possible – at least not for the time being. He therefore issued an order for U-boats to withdraw from the North Atlantic on May 24.

The quality of Allied warships, not least their weapons and U-boat detecting equipment, had risen dramatically since German submarines had been able to wreak havoc on convoys (especially during 1940 – 1941). The senior leadership of the Allied escorts – the skill of junior officers too – was also greatly improved.

Gretton, along with other escort group commanders, including the equally lethally proficient Donald Macintyre and ‘Johnny’ Walker, were now getting into their stride. As they wielded their ships to great effect, long-range air patrols by Allied air forces bore down heavily on the enemy too, at times scoring a similarly devastating rate of kills.

An Allied aircraft attacks a U-boat as the struggle in the N. Atlantic continues during WW2. Photo: US Navy/NHHC.

Amid all the memorializing of the great victories on land at the end of 1942 and in the first half of 1943, the great turning of the tide against the Axis – via the British victory at the Second Battle of El Alamein, the Sixth Army surrendering to the Russians at Stalingrad, the capture of 275,000 Italian and German troops in Tunisia and Americans triumphing at Guadalcanal – the significance of the convoy battles in the Atlantic of April and May 1943 can become forgotten. Such critical events in the turn of the tide at sea risk being lost amid the amorphous term Battle of the Atlantic.

Those laurels that were awarded to the warship captains who beat the U-boats came in the form of paper slips on which were written decryptions of coded signals conveying congratulations from senior commanders. In the aftermath of the fight to get ONS-5 through there was at least a message of thanks from Prime Minister Winston Churchill signaled to escorts.

One post-war admiral – a junior officer serving in destroyers during 1943 – judged Allied victories in the Battle of the Atlantic to be as great as any land victory. According to Vice Admiral Sir Roderick Macdonald, they were vital in ‘preparing the way for the invasion of Europe’. Had it been fought ashore, or even a sea engagement in the age of fighting sail, the ONS-5 victory ‘would be [lauded] in the history books, like Salamis or Trafalgar’ for it was ‘no skirmish’ and the battle ‘to defend convoy ONS-5 was of more significance than Alamein.’

That may be stretching it a little, but the point is well made, for pitched battles at sea do not leave behind scarred buildings or pockmarked bunkers, or wrecked tanks littering the landscape. Nor do the casualties lie in lovingly tended war cemeteries close to the scene of the battle to offer an all too tangible reminder of sacrifice.

Those who perished in the battles for convoys HX-231, ONS-5 and SC-130 lie in unseen and unknowable watery graves, vanished under the sea either inside their sunken ships and submarines or swept away by the cruel sea until absorbed into the vastness of the ocean.

Each merchant vessel that reached a UK port was another victory for the Allies in the struggle against the U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic during WW2. Photo: US National Archives.

Victory for the Allies was actually recorded in the ships the enemy never saw – the vessels that slid by the U-boats without a shot being fired and to enter a British port to offload their vital cargoes, all routine and largely unremarked. Each ship unloaded was, however, another small victory and diminished even further Germany’s chances of success.

Even though May 1943 is often regarded as the moment when the Battle of the Atlantic was won by the Allies – enabling the invasion of Normandy just over a year later – in reality the bitter struggle between Allied escorts/airpower and U-boats continued right until the end of the war in Europe. There were even fears the war at sea off Europe could still be lost by the Allies.

It morphed into a different kind of contest – in fact a series of contests stretching from the deep ocean to inshore waters around N.W. Europe – that at various times was arguably harder for the Allies to deal with, though the US Navy’s escort carrier hunter-killer groups reaped a devastating harvest in the mid-Atlantic, around the Azores. Tough as the fight may have become once again, British escort groups were relentless elsewhere.

The Allies feared the ‘U-boat peril’ (to borrow Churchill’s description) right up until the Reich’s total collapse, not just because of the looming (if troubled) introduction into service of the much-vaunted Type XXI and Type XXIII U-boats, but the Total Underwater Warfare concept.

Donitz hoped it could deliver final victory to Germany. So, in May 1943 the war of the transatlantic convoys may have peaked but now the battles had different objectives and the Allies’ hard won advantages were under threat of neutralization by Total Underwater Warfare.

Comments

Comments are closed.