‘This is a good book, a big book, and an important one’

Review of ‘Arnhem: Ten Days in The Cauldron’

by Dr Harry Bennett

The Acknowledgements of this book make it clear that it has been a labour of love, decades in the making for an author more usually well known for quality works of naval history. Ballantyne is both historian and a journalist which contributes to the authority and readability of his works for the general reader.

It is good popular history and high-quality writing that can get the narrative right, while offering fresh perspectives on a well-known subject, and, in this case, at the same time drawing the reader into the tone and fabric of the life and death struggle of the Airborne troops at Arnhem.

It is an exploration of that tone and fabric which is Ballantyne’s principal concern. Strategic and cultural issues (the rise to mythic status of parachute troops during the Second World War) are referenced and cleverly woven in throughout the main body of the book, which utilises a range of oral and other primary sources to give the reader a worm’s eye view of the fight for Arnhem. Those sources are well and appropriately referenced in endnotes, and a full bibliography, which is not always the case in popular histories of the Second World War.

Airborne troops fight at Oosterbeek. Via Australian War Memorial (AWM).

The approach of ‘Arnhem: Ten Days in The Cauldron’ is reminiscent of Stephen Ambrose at his best and Ballantyne doesn’t forget the civilians caught up in a brutal battle fought out in their homes, streets and their towns. For them the tragedy of Arnhem would see German forces remain in place just as liberation had appeared to dawn.

In terms of the experiences of the soldiers, Ballantyne ranges across the full scope of horrors facing Allied troops from transport in gliders made of wood and other light material, to facing off against the elite troops of Hitler’s SS, and the huge difficulties of trying to stop German vehicles (including armour) with light machine guns and limited anti-tank weapons. Narratives of individual soldiers and civilians can be followed as the reader is drawn into ‘The Cauldron’ of shrinking pockets of resistance and an operation going from risky to disastrous.

There is some remarkable evidence here and some remarkable stories, which Ballantyne neatly dovetails into a rolling epic, before concluding with an assessment of the wisdom of the operation, which concentrates on the views of those asked to carry it out.

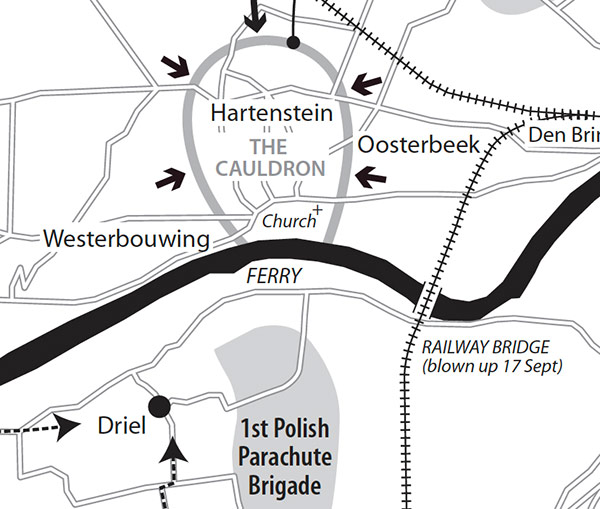

Arnhem battle map. © Iain Ballantyne Created by Paul Slidel

Ballantyne also traces the legacies and post-Arnhem struggles of participants, from survivors trying to come to terms with their days in ‘The Cauldron’, through to those on the run in the Dutch countryside hoping to make it back to Allied lines. For some, the last months of 1944-45 would be spent in German prisoner-of-war camps grimly hoping for liberation or enduring forced marches away from the advancing Russians.

As a teenager I laid a wreath at the Oosterbeek Cemetery. That cemetery is the last resting place of many of those who jumped as part of the attempt to seize Arnhem, together with the Polish paratroopers sent to support them, and even some of those in the division sent to relieve them up the -so-called ‘Hell’s Highway’.

I went through that cemetery looking at the groups of casualties, noting the stages of action in which they died. I can offer Ballantyne no higher tribute than to say that, as I read his book, 35-year-old memories of those groups of casualties in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery – and the questions about how they died – were vividly brought back to mind.

Ballantyne’s book shows how one tragedy is composed of many individual ones, and that behind every battle lost are many hundreds of personal struggles to win, to survive or to escape. This is a good book, a big book, and an important one.

Full details of the book here.

Dr Harry Bennett is an academic and historian and provided this objective assessment of the book in return for a review copy of the book.

Comments

Comments are closed.