D-Day Navies Pt1: Blasting the Atlantic Wall

The tendency among some accounts of the fighting that followed the D-Day invasion itself is to regard the struggle offshore as won after the troops got beyond the beaches. It does not reflect the fact that hundreds of vessels were engaged in providing a wide variety of support and in combat for some time afterwards.

They delivered supplies such as food and fuel, plus more troops and equipment while a variety of warships carried out bombardments of enemy formations inland and battered German coastal fortresses. They did all that while fending off determined enemy air and sea attacks.

Lunging out of a smokescreen laid by Allied vessels to protect their seaward flank off Sword Beach on D-Day itself were three German torpedo boats from Le Havre. Even though their crews were shocked and awed by the array of Allied firepower in front of them, these craft nevertheless launched 17 torpedoes.

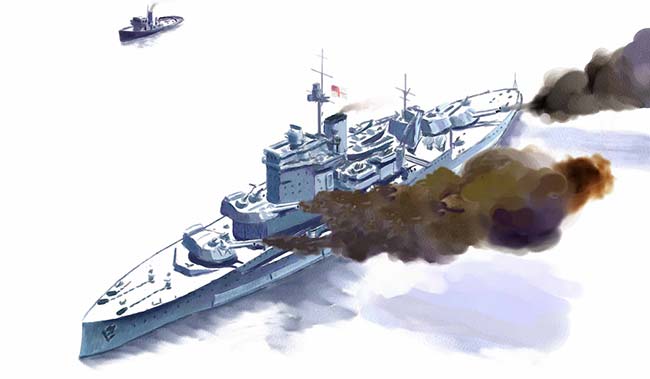

Watercolour of HMS Warspite bombarding German troops and armour on D-Day. Specially commissioned for ‘Warspite’ by Iain Ballanyne. Illustration by Dennis Andrews.

The British warships reacted on seeing splashes from the tinfish as they went in the water, the battleship HMS Warspite raining every calibre of shell possible down on the enemy. The torpedo boats turned around and made a speedy retreat back through the smokescreen, passing three of their own armed trawlers coming out to have a go.

The shells of Warspite and from other Allied naval guns followed the torpedo boats back through the smoke. One of Warspite’s scored a hit and instantly sank a trawler. In the meantime, the German torpedoes claimed a Norwegian destroyer, HNoMS Svenner, but otherwise found no victims. One of the tinfish passed harmlessly between Warspite and battleship Ramillies. The old battlewagons had survived the only naval surface action of D-Day.

The Norwegian destroyer HNoMS Svenner, which was blown apart on D-Day by German torpedoes that missed HMS Warspite. Photo: Strathdee Collection.

A few Allied naval vessels would in weeks to come become victims of U-boat attack. For example, the frigate HMS Mourne, was hit by a torpedo from U-767 on June 15 while engaged in an anti-submarine patrol to the south-west of Cornwall. She sank in less than a minute, with only 30 survivors out of her crew of 140.

The same day HMS Blackwood also sacrificed herself to protect vital troop and supply convoys across to Normandy. She was torpedoed mid-Channel by U-674, the frigate’s bows blown off and suffering 58 of her 157 sailors killed. An attempt was made to tow Blackwood back to port, but she sank off Portland.

And still the casualties at sea came, including the valiant mine-sweepers HMS Hussar and HMS Britomart. As the Allied armies finally made their breakout from the beachhead, Hussar and Britomart set about clearing a fresh path in to the coast, so British warships, including the battleship HMS Warspite, could use their big guns to hit enemy troops at Le Havre.

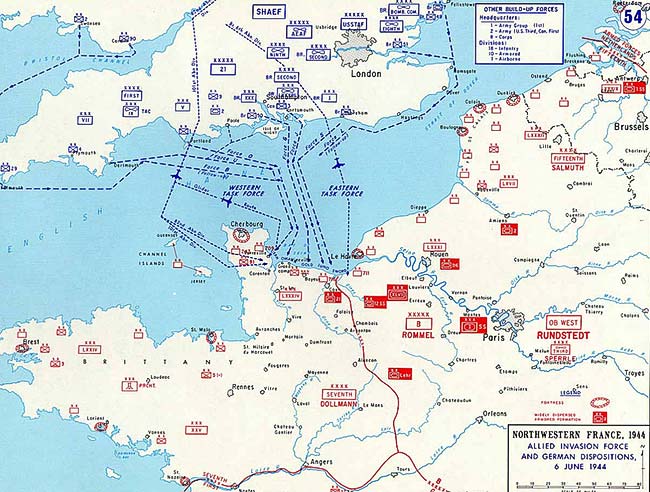

Contemporary invasion map, showing how the June 6, 1944 invasion of Normandy was launched and German forces facing it. Image: US Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC).

Ironically both mine-sweepers were sunk on August 27 by their own side. RAF Typhoon ground-attack aircraft attacked them with rockets, in the worst recorded case of ‘friendly fire’ suffered by the Royal Navy in WW2. Hussar lost 55 out of 80 sailors in her complement, while Britomart suffered 22 dead.

But no one should forget the men in the vessels that delivered the troops and their equipment to the beaches themselves – the landing ships and other assault craft – including HMLCI(L) 132 and HMLST 404, both lost carrying out that vital mission. Enemy mines claimed their share of Allied ships in the coastal waters off Normandy too.

The successes achieved by the U-boats were, on one hand, surprisingly few – bearing in mind seas thick with targets – but on the other much as expected. There was by the summer of 1944 massive Allied superiority on and over the sea, via dozens of anti-submarine task groups and U-boat killing aircraft.

Between June 7 and the end of the month 23 U-boats were sunk, with 12 of them in the English Channel or the Bay of Biscay, and including one scuttled at Lorient as not worth repairing. Just sending a U-boat out seemed tantamount to suicide. By June 10, the U-boat Force command realised it was pointless to even try deploying non-snorkel submarines. Those boats were confined to base.

U-boats in the Bay of Biscay were advised to lie on the bottom to conserve battery power and await a chance to attack Allied shipping if further landings were made on the Biscay coast. Boats in the Channel were as matter of practice permitted to return home if enemy defences proved too tough.

Better times for Germany’s U-boat force: U-428 returning to Lorient on the French Atlantic coast, after hunting Allied merchant shipping off the east coast of the USA in 1942. By the summer of 1944 it was the U-boats that were the hunted. Photo: NHHC.

Having been forced to abandon regular wolf pack attacks against shipping in the North Atlantic, the U-boat Force now appeared to have lost the battle for the English Channel and Bay of Biscay. Only one U-boat got through to waters right of the invasion beaches to sink a vessel, a landing ship.

The so-called Grey Wolves, who had once ranged across the Atlantic to ravage convoys, were now reduced to skulking on the bottom of the sea within a few miles of their besieged bases which were under almost constant air attack.

Comments

Comments are closed.