Secrets of the UK’s true-life ‘Hunter Killers’

‘…there are two ways of dying in the circumstances in which we are placed…The first is to be crushed; the second is to die of suffocation. I do not speak of the possibility of dying of hunger, for the supply of provisions in the Nautilus will certainly last longer than we shall. Let us then calculate our chances.’

Such are the words of Captain Nemo in Jules Verne’s, ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea’, a ground-breaking novel (published in 1870) that depicted havoc caused across the oceans by a revolutionary type of submarine.

It was fast and could inflict instantaneous destruction on surface vessels – it struck without warning and then was gone again. It was a type of fighting vessel that did not really become reality until the advent of nuclear-powered submarines in the 1950s.

The face-off between the West and the Soviet Union was threatening to burn white hot and during that so-called Cold War there were two competitions – one for command of outer space and the other for control of inner space.

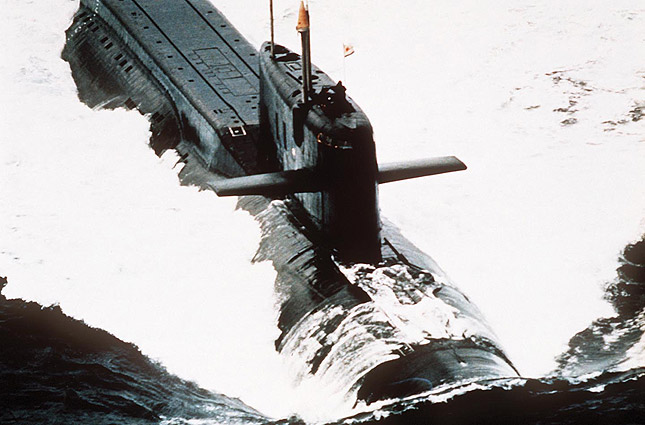

Enemy of the West (and a target for British and American attack submarines): A Yankee Class missile submarine of the Soviet Navy underway. Photo: US DoD.

We know plenty about the former and of the latter, hardly anything at all. The general population arguably knows more about outer space than the inscrutable depths of the seven seas, where not only the fictional Nemo lurked but so did real flesh and blood men of the submarine services.

The more crucial competition was not the outer space race, but the bitterly fought contest waged by the USA, Britain and USSR across a darkly secret maritime battle space.

For nearly five decades humanity’s fate was actually held in the hands of those who voyaged not across the airless void to the moon, but of men who silently, secretly and without fanfare or adulation – either then, or now – sailed in the silent deep of the world’s oceans. They were the Cold War submariners.

Year after year they took their vessels out on deployment, disappearing beneath the surface of the sea for weeks, if not months, at a time. Between the last time they saw their homeland and the next, babies were born and loved ones died. Wars might be fought or peace and goodwill reign.

Deep in the oceans, throughout every personal tragedy and triumph, each world-shaping event, they hovered, unseen and ignored by the majority of mankind, on the edge of the abyss. Not only was their deadly theatre of the Cold War literally hidden from the eyes of all except them, the secrecy imposed on both sides was almost all encompassing.

Very few shafts of light fell on what really happened and, even to this day, it remains mostly in the shadows. The campaign waged beneath the waves by British submariners for nearly five decades was the most dangerous of plays in the East-West confrontation and they evolved into its deadliest practitioners.

Last of the Cold War warriors: The British nuclear-powered attack submarine HMS Sceptre returns to Devonport in 2010 at the end of a career that started in the late 1970s, at the height of the East-West confrontation. Photo: Nigel Andrews.

‘Hunter Killers’, aims to present an insight into the enduring hazards and hardships of life in submarines of the Royal Navy engaged in that very risky game. Out there, in the vast ocean, responsibility for the safety of nuclear-propelled submarines and their crews, often manoeuvring in rather close proximity – and occasionally coming to grief, as ‘Hunter Killers’ reveals – fell on the broad shoulders of a few remarkable men.

The tale I weave is not the story of the Royal Navy, or of its submarine service per se. Yet, while the experiences recounted are unique to those players in this ‘Hunter Killers’ production, they still serve to represent the broader story.

The same could be said of the stories told by a small supporting cast of ratings whose fate the officers decided. They also stand as representatives of an amazing breed of men in the cast of an expansive, yet deeply personal, drama.

At times such men held more destructive power in their hands than had ever been unleashed on the planet. The Cold War submarine captains often had to take split-second decisions upon which the lives of not only their own sailors might depend but also those of millions living ashore in complete ignorance of the high stakes poker game unfolding at sea.

To them we owe our very survival as a species, the continued existence of this planet, for they did not bungle the knife-edge game. A single rash action or error of judgment could have led to Armageddon.

Today we grapple with different life and death matters on the world stage in a radically changed society. We forget how turbulent, how terrifying and exciting it could sometimes be to live back then.

‘Hunter Killers’ also seeks to set the submariners’ story within the context of an amazing military-technical evolution that extended from the deep oceans to outer space. Nowhere was the cutting edge of science more crucial than in the face-off beneath the waves. Gaining knowledge of each other’s technology was one of the key prizes.

Espionage lay at the heart of British and American submariners’ activities – whether striving to record the distinctive sound signatures of Soviet submarines and surface ships, or eavesdropping on, and covertly observing, missile tests and other military and naval activities. To know an enemy’s vulnerabilities – and capabilities – without him realising you had gained that insight was the ultimate. It awarded the possessor a killer edge. Nobody was a more formidable deep cover agent than the Royal Navy submariner of the Cold War. It is therefore about time we knew at least who some of them were, in order to understand what they all did, or at least as much as secrecy rules will permit us to reveal.

In that way we can at last fully understand what the rest of us actually lived through. For without this story there are pieces of the Cold War jigsaw missing, the full truth obscured. In ‘Hunter Killers’ we voyage in the company of a Band of Brothers, pushing back the boundaries of human endurance. We venture into their realm of wondrous mystery and sometimes terrifying incident.

Submariners inhabit a world unto its own, but one that deserves to have its triumphs and terrors better known. Winston Churchill appreciated its unique hazards. The former First Lord of the Admiralty paid this tribute: ‘Of all the branches of men in the forces, there is none which shows more devotion and faces grimmer perils than the submariners.’

The mindset in the Royal Navy during the Cold War was that the Submarine Service was the pre-eminent arm. For the most serious threat to the existence of the West at all levels came from beneath the surface of the sea.

There were Soviet nuclear missile submarines (SSBNs) ready to wipe out all civilization, not forgetting guided missile submarines and attack boats that could, in time of war, cut supply lines across the Atlantic, starving NATO of troop reinforcements. They could also deny the civilian population food, energy and many other goods considered essential to daily life.

The Russians had hundreds of submarines of all varieties and nothing that floated on the surface of the sea – whether warship or merchant vessel – was safe from them. The only answer was for NATO to field better hunter-killer boats to hunt the enemy down and to meet burgeoning Soviet SSBN destructive power with Royal Navy ‘bombers’ and US Navy ‘boomers’.

Unable to match Soviet numbers, the key to winning was in the fine margins of tactical success. And that is where the British submariners proved their worth. The Royal Navy may not have fielded the most submarines during the East-West confrontation, but it sent them into the danger zones where it mattered.

The ultimate tribute to the Royal Navy’s operators perhaps came from the late Tom Clancy, for the novelist got to know a lot of submariners from the principal Cold War nations.

His verdict was that ‘while everyone deeply respects the Americans with their technologically and numerically superior submarine force, they all quietly fear the British.’ Clancy went on: ‘Note that I use the word fear. Not just respect. Not just awe. But real fear at what a British submarine, with one of their superbly qualified captains at the helm, might be capable of doing.’