Kremlin sends out ASW ‘search-and-strike’ group

• Strike carrier reinforces Med US Navy presence

• Is Russian ‘carrier-killer’ submarine being deployed?

• Only the latest naval face-off in Med

Heavy-hitting reinforcements for US Navy forces in the Mediterranean have now arrived, with the USS Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group (HSTCSG) and its powerful array of warships completing the trans-Atlantic crossing in just over a week.

They join US Navy’s Sixth Fleet area of operations (AOR) at a time of continuing high tension between Russia and the West. The entry of the Harry S. Truman comes less than a week after bombardment of suspected chemical weapons sites in Syria by US Navy surface warships and a submarine, along with a French frigate – all firing cruise missiles – in tandem with air strikes by jet fighters from the USA, France and the UK. The cruise missiles fired by the US Navy attack boat USS John Warner were the first ever fired in anger by a submarine of the Virginia Class, the American navy’s latest SSN type.

The US Navy attack submarine USS John Warner in the Mediterranean. She has since launched cruise missiles against targets in Syria. Photo: NATO.

Within days of the Syria strikes, the Kremlin deployed an Anti-submarine Warfare (ASW) ‘search-and-strike group’, as the Russian Navy termed it, from the Northern Fleet in the Arctic. The destroyers Severomorsk and Vice Admiral Kulakov (both Udaloy I Class ships) were, according to the Russians, in the Barents Sea conducting a ‘test tactical drill on searching for and destroying’ what was further described as a ‘simulated enemy submarine’.

One of the Russian destroyers engaged in the Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) exercise in the Barents Sea. Photo: Russian defence ministry.

However, it was not beyond the bounds of possibility that the Russian exercise was in reality a means to sanitise exit routes for Russian submarines being deployed to go and shadow the Harry S. Truman and her battle group. A potential candidate for that mission is the Oscar II Class ‘carrier killer’ submarine Oryol, which last year emerged from a major refit. The 24,000 tons (dived) submarine is now armed with 3M-54 Kalibr land-attack and anti-shipping cruise missiles.

The Northern Fleet nuclear-powered Oscar II Class ‘carrier killer’ submarine Oryol returning to her base in the Kola Peninsula after her major upgrade. Photo: Russian defence ministry.

If Oryol has been sent out, Russian attack submarines would also have been deployed to ‘delouse’ waters off the main naval bases in the Kola Peninsula, in case there were any NATO submarines snooping around – although one of them could not be the British hunter-killer boat HMS Trenchant. Following her dramatic exploits alongside American submarines in the Arctic, surfacing through polar ice, the Trafalgar Class SSN this week sailed into Submarine Base New London, on the east coast of the USA, for a port visit.

HMS Trenchant approaches the pier at Naval Submarine Base New London for a port visit after participating in ICEX 2018. Photo: US Navy.

Scheduled to last several days, the Russian ASW exercise in the Barents was due to involve ‘tasks of engaging the simulated submarine enemy,’ according to the Russian defence ministry. It also advised that its ASW warships would ‘conduct torpedo firing with practical ammunition.’ During the old Cold War between Russia and the West this might have been considered convenient cover for the pursuit of a NATO submarine on surveillance mission in the Barents.

From the late 1940s to the early 1990s there was an almost continual forward deployment of US Navy and Royal Navy submarines into the Barents – considered by the Russians to be Mare Nostrum – to gather intelligence on weapons tests and the latest surface ships and submarines operated by the foe. Armed with sound signature and radar emissions intelligence, and details of weaponry, NATO hoped to stand a better chance of fighting off any massive Soviet surge into the North Atlantic if the Cold War turned hot.

As the Russian ASW ‘exercise’ got underway in the Arctic this month, a highly significant face-to-face meeting was being held in Baku, Azerbaijan, between NATO’s current Supreme Allied Commander Europe, US Army General Curtis Scaparrotti and the Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces, General of the Army Valery Gerasimov.

The neutral ground summit was called to discuss relations between NATO and Russia, but was surely also a means to ensure Moscow’s military and those of Western nations do not clash in any future episodes in which weaponry is unleashed to against Syrian targets. A Russian defence ministry account explained: ‘They also exchanged views on the situation in Syria, stressing the necessity of cooperation in fighting against international terrorism.’ For the Russians the latter group does not include President Assad’s regime in Syria, however.

The USS Harry S. Truman is no stranger to operations in the US 6th Fleet AOR, having been sent there to conduct strikes on ISIL targets in Syria in the summer of 2016. The US Navy has in the past frequently also stationed a strike carrier in the neighbouring 5th Fleet AOR – covering waters off Arabia – but at the time of last weekend’s strikes on Syria, the assigned ship, USS Theodore Roosevelt, was in the South China Sea, another zone of increased tension at sea.

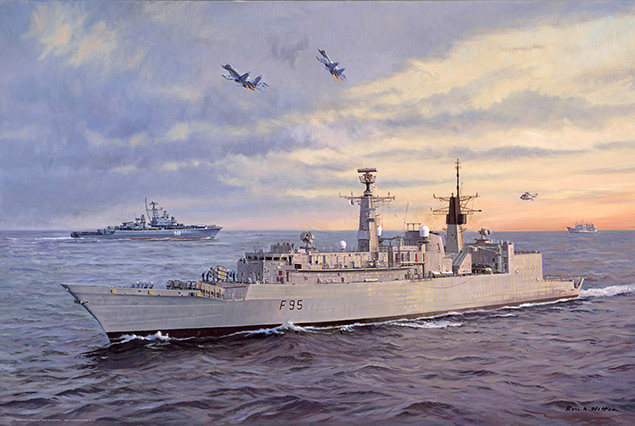

The US Navy strike carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower in the eastern Mediterranean while working with the French carrier FS Charles de Gaulle. Photo: US Navy.

Russian submarine deployments to shadow American Carrier Strike Groups in the eastern Med are nothing new either. In late 2016 NATO warships detected and then tracked at least one Russian nuclear-powered submarine sent from the Northern Fleet to shadow the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower. This came as the Nimitz Class carrier was conducting joint strike operations against Islamic State targets in Syria with the French Navy strike carrier FS Charles de Gaulle.

Around the same time NATO also sent its submarines to shadow Russia’s carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov. As related in ‘The Deadly Trade’ the Russian defence ministry claimed it had been forced to order Vice Admiral Kulakov and Severomorsk – the same ships involved in today’s ASW exercise in the Barents – to chase away a Dutch diesel-electric submarine attempting to trail the Kuznetsov (as the carrier prepared to launch her own jets on missions against Syrian targets).

More on the undersea and surface navy face-off between Russia and the West in recent years and during the Cold War is to be found in ‘

More on the undersea and surface navy face-off between Russia and the West in recent years and during the Cold War is to be found in ‘