Hunt for Missing Jetliner

(Reflects Echoes of WW2’s HMAS Sydney Disappearance)

The massive naval-led effort to solve the mystery of what happened to Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370 had at the time of writing not yielded even a scrap of solid evidence. This was despite the efforts of multiple Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA), surface vessels and at least one nuclear-powered submarine.

For all the powerful sonars, surface search radars and Number One Eyeballs, reports of possible debris were red herrings – items spotted in the sea turned out to be flotsam and jetsam. An examination of the seabed where a suspected black box pinger was detected, using a mini-submarine operated from an Australian vessel, looked certain to be fruitless. Hopes rose when likely looking debris was found on the shores of western Australia, but this also turned out to be a false lead.

More and more the agonising case of MH370 started to resemble another disappearance in the same waters more than 70 years earlier, that of HMAS Sydney. As was the case with the vanishing Royal Australian Navy (RAN) light cruiser in WW2, conspiracy theories started to fill the knowledge vacuum.

Outlandish proposals included claims the US military had taken over the jetliner by remote control – to intercept weapons systems and/or espionage operatives bound for China – and had then flown it to Diego Garcia before disposing of passengers and crew. Why the US Department of Defense (US DoD) and its allies would go through the charade of devoting numerous, expensive assets and personnel to then searching for MH370 was not credibly explained.

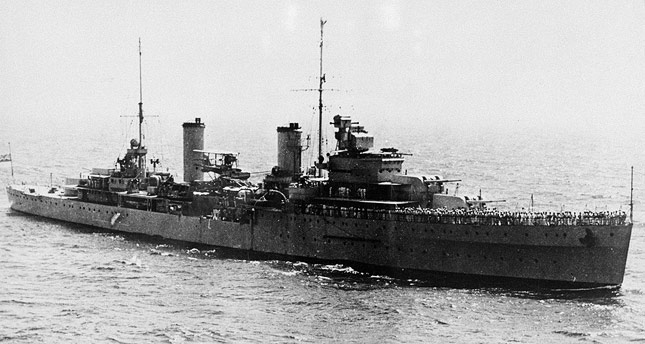

Such ideas reflected theories that sprang up in the wake of the warship’s disappearance more than seven decades earlier. In November 1941, HMAS Sydney was destroyed after being surprised at point-blank range by the disguised Nazi surface raider Kormoran. Sydney was last seen steaming out of control and on fire into the blackness of night. Kormoran also sank, but with survivors who were later captured.

The light cruiser HMAS Sydney, pictured several months before she disappeared in mysterious circumstances after a battle off western Australia. Photo: Commonwealth of Australia.

Sydney took all 645 Australian and British sailors aboard to their deaths. Nobody caught sight of HMS Sydney for nearly 67 years. That was when undersea wreck hunter David Mearns found her in very deep waters beyond western Australia (in March 2008).

In the intervening years conspiracy theories included a claim HMAS Sydney was sunk by the Japanese, as a precursor to Pearl Harbor. Prior to the discovery of the HMAS Sydney and Kormoran wrecks by Mearns, only tantalising fragments of wreckage, and even the corpse of a sailor washed ashore at Christmas Island, were found. Nothing, except for an empty carley float, was positively identified as being from HMAS Sydney

David Mearns has this spring been consulted by those keen to pick his brains for how the wreckage of MH370 might be located, not least by rolling news channels around the globe desperate to say something in the absence of nothing concrete to report. On April 16, Mearns was confident enough the wreckage site had been found to tell Australia’s ABC News: “I think essentially they have found the wreckage site. While the [Australian] Government hasn’t announced that yet, if somebody asked me: ‘Technically, do they have enough information to say that?’ My answer is unequivocally ‘Yes’.”

A Sailor aboard the Australian naval support ship HMAS Success endures wet and freezing conditions while using binoculars to search for evidence of missing MH370. Photo: ABIS Julianne Cropley/RAN.

Aside from the detection of possible black box pings by vessels involved in the search for MH370, Mearns based his confidence on gut instinct and experience. He had been involved in locating Air France Flight 447, which in 2009 crashed into the Atlantic off Brazil, with no survivors. “You just don’t hear these [black box] signals randomly in the ocean,” he told ABC. “These are not fleeting sounds – they have got four very, very good detections, with the right spectrum of noise coming from them. It can’t be from anything else.” Confirmation would come when photographic evidence of the jetliner wreck on the seabed was obtained.

Meanwhile, the search for whatever remains of MH370 continued. Key players have included the British survey ship HMS Echo and the nuclear-powered attack submarine HMS Tireless, the latter using her immensely powerful passive sonar to investigate leads. Tireless was pulled off the task in late April, returning to her more usual missions somewhere else in the Indian Ocean.

A Royal Australian Air Force AP-3C Orion aircraft flies past HMS Echo while both are searching for missing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370. Photo: Australian defence ministry.

The Echo was initially tasked with searching a 1,000 square mile area following the detection of a potential black box pinger by the Chinese vessels Haixun and Dong Hai Jiu (at the beginning of April). By then Echo had already used her sophisticated sidescan sonars to, according to a UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) source, “search an area ten times the size of Greater London – some 6,000 square miles of ocean.”

The MoD source added: “Echo’s hi-tech sonar has been specially adapted so it can pick up any transmissions on the black box’s frequency. This is the first time Echo’s sonar has been used this way and so far it has located several possible contacts – but sadly none of them proved to be from MH370’s black box.”

The Devonport-based survey vessel’s captain, Commander Phillip Newell, revealed that the 60 men and women in his ship’s company were applying themselves totally to the search. “They are working 24/7 to find MH370,” he said. “They are young, bright and enthusiastic and will step up to every challenge in the search for the missing aircraft.”

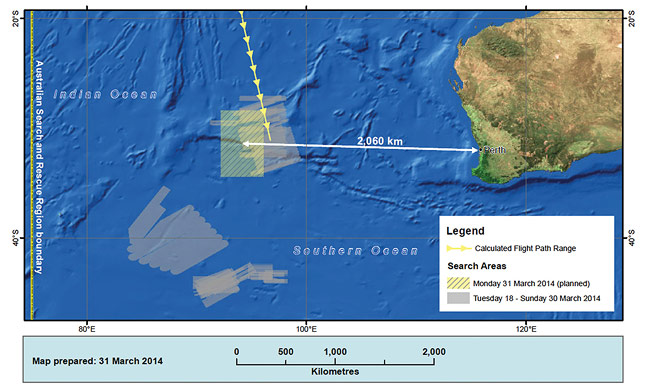

Graphic showing search areas off western Australia, in the same zones where it was suspected HMAS Sydney vanished in WW2. Image: AMSA.

In late April Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott made a telling observation that dented the hopes of relatives of 239 people who disappeared with Flight MH370 – but nonetheless was a painful truth that had until then been not much addressed in public (and certainly not by politicians).

Prime Minister Abbott told a press conference the hunt for potential surface debris from MH370 was over and that search efforts would now be concentrated on the ocean floor, across a vast area of the Indian Ocean off Western Australia.

He suggested that there was a possibility the wreckage of the jetliner would never be found, though he vowed that he would do his bit to ensure every effort possible was made to find MH370.

Those words again echoed what happened all those many years ago. The search to find HMAS Sydney – and solve the mystery over what fate befell her and the men in her – was an agonising decades-long saga that traumatised the Australian nation. Fixing the exact fate of MH370 agonises many across the world. It pains even those without lost loves ones. They cannot bear the fact that such things can happen, despite our so-called all-seeing, inter-connected, high-tech world.

Even with all of today’s sophisticated sonars in surface ships and submarines, far-ranging maritime patrol aircraft and satellites, the vast ocean does not give up its secrets easily, if at all.

A version of this article will be published in the forthcoming edition of WARSHIPS IFR magazine, which is due out on May 16. Visit the magazine’s site for more naval news, commentaries and analysis: For more on the mystery of HMAS Sydney, investigate the DVD production ‘Sydney, Cipher and Search – The Inside Story’, which was produced and directed by Iain Ballantyne with Stuart Rogers. It can be purchased via Amazon.

Also read the book by Captain Peter Hore, ‘Sydney, Cipher and Search’ (Seafarer Books, £9.95, paperback) available from Amazon and direct from Seafarer Books.