Only the Dead Have Seen the Last of Submarine Warfare – Part One

Iain Ballantyne, author of ‘The Deadly Trade: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’, begins a two-part look at the contours of a fast evolving new struggle in which the UK’s submarines and surface forces will inevitably be required to play a key role.

Whether it has been the French, US-based Fenians pursuing the cause of Irish Liberation, the German Navy – by order of the Kaiser and later the Fuhrer – or the Soviet Union, the enemies and potential foes of Britain and its allies have over many decades enthusiastically pursued submarine warfare.

While we are unlikely to see vast, epic clashes as occurred during the two world wars, it is likely only the dead have seen the last of submarine warfare (to adapt a famous phrase coined by the philosopher George Santayana – NOT Plato as some have claimed – who wrote in 1922: ‘Only the dead have seen the end of war’).

In fact, submarines of the West and Russia have in recent times frequently unleashed weapons in anger – to strike deep inland, via cruise missiles, rather than using torpedoes to sink ships – while a new Cold War-style confrontation is also evolving across the oceans, stretching all the way from the North Atlantic and Mediterranean to the South China Sea.

Symbol of a resurgent Russia under the sea: The Improved Kilo Class submarine Rostov-on-Don, which Moscow has used to fire Kalibr cruise missiles into Syria. Photo: © Cem Devrim Yaylali. https://turkishnavy.net

Today Russia is deploying more and more submarines to test the defences of NATO nations and a high priority in the North Atlantic remains detecting and trailing the nuclear deterrent boats of the UK, USA and France. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, the assault ship HMS Albion in the late summer of 2018 made her presence felt in the South China Sea, where she conducted a Freedom of Navigation Operation (FONOP) in waters that Beijing has (illegally) claimed sovereignty over. China has flouted international law by constructing a chain of fortresses on reefs and small islands, in a bid for total dominance of surrounding waters (and in which it intends to create Soviet-style bastions to protect its nuclear missile submarines). The Royal Navy has joined the American, Japanese and Australian fleets in agreeing on a major effort to show China it cannot restrict rights of transit through such key zones.

Arguably the best counter to Russia’s submarines lurking on the edge of UK territorial waters – or the Chinese seeking to exert unwarranted control on (or under) the South China Sea – is another submarine, namely a nuclear-powered hunter-killer. In that respect the British have something to offer. Despite difficulty maintaining force levels since the end of the Cold War they have preserved a reputation as deadly exponents of submarine operations.

Given the hostile attitude of many Royal Navy admirals in the early 1900s to the mere idea of submarines, development of such expertise over the years was not necessarily a given. Yet the RN’s submarine arm has achieved many feats in combat, some of which have yet to be equalled (which, let’s face it, is actually a good thing as it means an absence of major sea wars).

The one confirmed instance of a submarine destroying another while both were submerged remains HMS Venturer’s sinking of U-864 off Norway in early 1945. The only time a nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine has sunk a surface vessel in time of war remains HMS Conqueror’s attack on ARA Belgrano during the 1982 Falklands conflict. Since WW2 the only other episodes in which submarines have sunk surface vessels using torpedoes are the sinking an Indian frigate by the Pakistan Navy boat Hangor (in the early 1970s) and destruction of a South Korean corvette by a North Korean craft in 2010.

The assault ship HMS Albion calls at Yokosuka, Japan, prior to her recent patrol in the South China Sea. Photo: US Navy.

During the latter stages of Cold War – which saw plenty of dangerous moments that, thankfully, did not result in actual, full-on submarine versus submarine combat – the novelist Tom Clancy upset his own nation’s navy by paying tribute to Britain’s formidable submariners rather too enthusiastically.

‘While everyone deeply respects the Americans with their technologically and numerically superior submarine force, they all quietly fear the British,’ Clancy observed. He added: ‘Note that I use the word fear. Not just respect. Not just awe. But real fear at what a British submarine, with one of their superbly qualified captains at the helm, might be capable of doing.’ Those skills were very much in demand during the confrontation between NATO and the Soviet Union, with British submarines on the leading edge of a high stakes poker game under the waves, which saw numerous close shaves.

Watching the Hollywood version of Clancy’s best selling-novel, ‘The Hunt for Red October’, the other day, it struck me that it no longer seems like a 1980s museum piece. Today we are back in ‘a war with no battles, no monuments’, as Captain Marko Ramius (played by Sean Connery) puts it in the movie. The revival in Hollywood interest in submarine movies, such as ‘Hunter Killer’ [not based on my own book] and the forthcoming ‘Kursk’ reflects the upsurge in tensions and rivalry and under the sea between East and West (as well as the enduring appeal of submarine dramas).

For the West is confronted with what Vice Admiral James Foggo USN in 2016 described as a fourth Battle of the Atlantic – following on from those of the 20th Century’s two world wars and the Cold War – in which a new generation of Russian submariners are seeking to dominate the oceans. In October 2015 another senior USN officer, Admiral Mark Ferguson, who at the time commanded NATO’s Allied Joint Force Command and US Navy forces in Europe and Africa, depicted Moscow as constructing ‘an arc of steel from the Arctic to the Mediterranean’ by deploying ‘a more aggressive, more capable Russian Navy’.

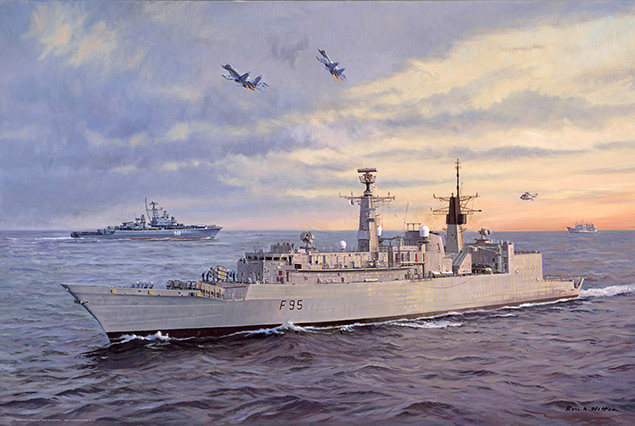

Holding the line in the new Battle of the Atlantic: The Royal Navy nuclear-powered attack submarine HMS Trenchant. Photo: US Navy.

The Russians mean to exert this decisive presence as part of a global maritime challenge to the West. At the beginning of 2015 Russian submarines reportedly tried to detect – and then trail – one of the UK’s Trident submarines as the latter departed (or returned to) its base on the Clyde. Having cut the RN’s frigate force and axed the Nimrod anti-submarine aircraft, under the calamitous 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR), the UK Government had to ask its allies to help hunt down the intruder or intruders (a job previously performed by the Royal Navy in tandem with the RAF).

In fact, since 2014 – following the Crimean annexation that heralded a more aggressive Russian military – Moscow is suspected of regularly sending its submarines to stray close to, or even sneak into, territorial waters of not only the UK and USA, but also Sweden, Finland, Norway and the Baltic States.

Fears were raised at the end of 2017 that the Russians might even use their submarine forces to attack the UK’s seabed infrastructure, such as Internet cables and energy pipelines. This was surely not unexpected? Since WW2 the capability to interfere with (or sever) underwater cables has been pursued by leading submarines forces (of both East and West). For example, during WW2 the Royal Navy made a major effort to cut seabed communications links between Japanese garrisons scattered across Asia. The latter day effort by the Russians serves only to enhance the contention that we have not seen the end of submarine warfare – in all its many forms.

This is an adapted version of an article that was published in The Association of Royal Navy Officers Newsletter (Summer 2018)

xx

More on the undersea and surface navy face-off between Russia and the West in recent years and during the Cold War is to be found in ‘

More on the undersea and surface navy face-off between Russia and the West in recent years and during the Cold War is to be found in ‘