U-Boats versus escorts in the Battle of the Atlantic

…and submarine warfare across the centuries

‘The Deadly Trade’ takes readers on an epic voyage through submarine warfare, including how U-boats in two world wars tried to achieve victory, first for the Kaiser and 20 years later for Adolf Hitler.

The action-packed narrative includes bitterly contested Battle of the Atlantic convoy fights of WW2. ‘The Deadly Trade’ tells the stories of Britain’s formidable submarine-killing escort group leaders, including Frederic ‘Johnny’ Walker, Donald Macintyre and Peter Gretton, while looking at the technological game of leap-frog played by both sides to try and gain the winning edge.

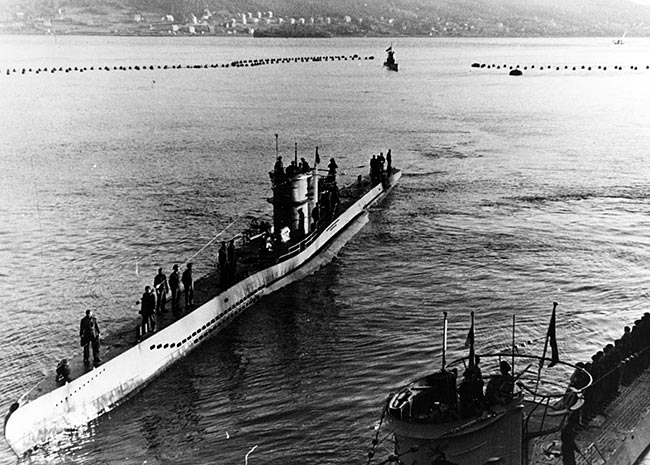

An Atlantic convoy under heavy Allied escort in 1943. Photo: USN/US National Archives.

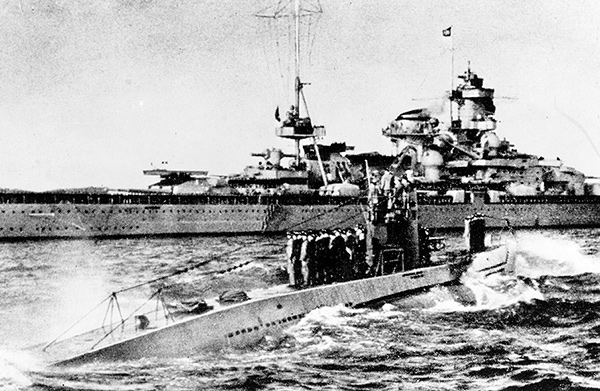

We sail to war with submarine ‘Aces’ Otto Kretschmer, Gunther Prien, Joachim Schepke and Fritz-Julius Lemp and on the Allied side learn of exploits by Britain’s Malcolm Wanklyn in the Mediterranean, and the USA’s Dudley Morton, Richard O’Kane and Sam Dealey in the Pacific.

The anti-submarine corvette HMS Loch Killin, which sank U-736 in August 1944. Photo: Strathdee Collection.

Included in this globe-spanning tale are the famous Enigma machine and code book captures that played a key role in deciding the outcome of WW2, along with a broader look at the naval intelligence contest so crucial in the Battle of the Atlantic and the Pacific.

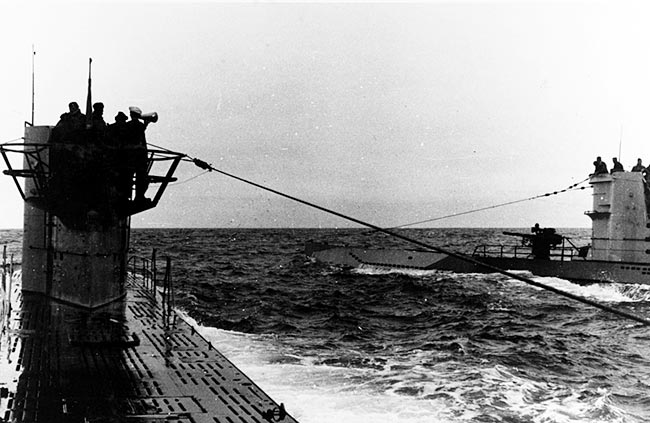

A U-boat sinks a British merchant vessel in the early days of WW2. Image: US Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC).

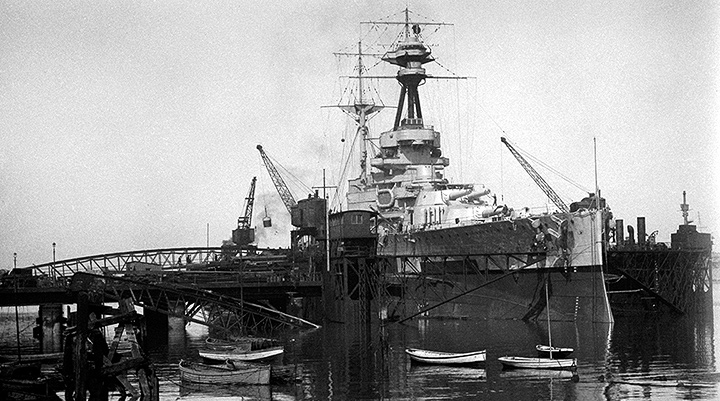

‘The Deadly Trade’ tells the story of how tiny craft took on massive battleships, including U-boats sinking the Royal Navy’s HMS Royal Oak and HMS Barham in WW2, along with the incredible exploits of British submariners in the Dardanelles and Baltic during WW1. The deeds of Japanese and Italian submarines in WW2 are not overlooked. We also learn how close the Kaiser’s U-boats came to starving Britain and collapsing the entire Allied war effort in 1917, as the first Battle of the Atlantic peaked.

Before telling the story of submarine warfare during two global conflicts of the 20th Century, ‘The Deadly Trade’ presents the amazing stories of submarine technology pioneers such as Cornelius Drebbel, Robert Fulton and John Philip Holland (between the 1600s and early 1900s). This opens up a window on the primitive attempts to create workable undersea warships in confrontations between England and its enemies in the 17th Century, as well as during the American War of Independence, Napoleonic Wars, American Civil War and the Crimean War.

WW1 undersea warriors in the action-packed narrative include Max Horton of the Royal Navy, whom the Germans feared so much they hired assassins to eliminate him, and Georg von Trapp, of ‘Sound of Music’ fame, who was Austria’s top U-boat captain.

When it comes to WW2, the book looks at the role of submarines in the clash of battle fleets at Midway in June 1942. How the US Navy submarine service brought the Empire of Japanese to its knees in 1945 – even before the atomic bombs were dropped – is explained too, via the stories of daring American submarine captains and their famous craft.

Two American submarine ‘Aces’ of WW2: Dudley Morton (right) and Richard O’Kane on the bridge of the USS Wahoo. Photo: USN/US National Archives.

We dive into unconventional submarine warfare, including Japanese midget subs during the notorious Pearl Harbor raid plus British X-craft against the Nazi battleship Tirpitz in Arctic waters and the Japanese heavy cruiser Takao at Singapore.

As WW2 approaches its finale we discover how the Germans set out to pursue Total Underwater Warfare, partly via the revolutionary Type XXI U-boat. The incredible story of a proposed cruise 1945 missile attack on New York is told, while the likelihood (or otherwise) of Hitler escaping to South America in a U-boat is considered when telling the story of U-977, which made the journey as the Reich collapsed.

‘The Deadly Trade’ takes us into the post-WW2 Cold War face-off between the Soviets and NATO including dangerous jousts below the waves between Western and Russian submarines. The book also tells the inside story of how the Pakistan Navy submarine PNS Hangor in the early 1970s sank the Indian frigate INS Khukri. The attack on the Argentine cruiser ARA Belgrano by the British nuclear-powered attack boat HMS Conqueror features in chapters on the submarine side of the Falklands War.

The Trafalgar Class hunter-killer submarine HMS Turbulent returning to Devonport after action in the 2003 Iraq War. Photo: Tony Carney.

‘The Deadly Trade’ concludes with a look at today’s global submarine arms race and the continuing use of submarines to try and gain geopolitical advantage. Outlined are President Putin’s ‘missile boat diplomacy’, along with the use of cruise missiles by the British and Americans to try and decapitate rogue regimes headed by the dictators Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi.

Winston Churchill observed: ‘This episode, which must be regarded as a feat of arms on the part of the German U-boat commander, gave a shock to public opinion.’ It would be six months before Scapa Flow’s defensive gaps were plugged and the Home Fleet could return in safety to its principal war anchorage. Meanwhile, Prien and the crew of U-47 reached Wilhelmshaven on October 17 to be acclaimed national heroes. During an audience with Adolf Hitler in Berlin, U-47’s commander was presented with the Knight’s Cross. The Fuhrer hailed Prien’s achievement as ‘a unique triumph.’

Winston Churchill observed: ‘This episode, which must be regarded as a feat of arms on the part of the German U-boat commander, gave a shock to public opinion.’ It would be six months before Scapa Flow’s defensive gaps were plugged and the Home Fleet could return in safety to its principal war anchorage. Meanwhile, Prien and the crew of U-47 reached Wilhelmshaven on October 17 to be acclaimed national heroes. During an audience with Adolf Hitler in Berlin, U-47’s commander was presented with the Knight’s Cross. The Fuhrer hailed Prien’s achievement as ‘a unique triumph.’