‘Bismarck had to be stopped’

As the Swordfish torpedo-bombers headed back to the carrier HMS Ark Royal on the afternoon of 26 May 1941 they came across some other warships, which might well be the enemy.

The attention of formation leader, Lieutenant Commander James Stewart-Moore, was drawn to one of his own aircraft, which was equipped with air search radar. Via semaphore flags, a young officer in its crew indicated to his leader that a contact had been picked up, around ten miles away.

Destroyers came into view below, which the aviators at first suspected might be German ships coming out to help escort Bismarck to a French port. However, they flashed a British identification signal.

It was Captain Philip Vian’s 4th Destroyer Flotilla, battling rough weather in poor visibility as it struggled south. Aboard Vian’s flotilla leader, HMS Cossack, was 18-year-old junior rating Ken Robinson, a loader on the ship’s 2pdr pom-pom anti-aircraft weapon. He would recall that one of the biplanes flew “practically alongside as the pilot waved to us before they flew away.”

The torpedo-bombers turned back towards Ark Royal. They were actually returning to the carrier in humiliation, for, prior to encountering Vian’s destroyers, the Swordfish had mistakenly attacked the cruiser HMS Sheffield. The latter was shadowing Bismarck at the time but fortunately, the torpedo attacks caused the cruiser no harm, though her crew were somewhat furious.

With their aircraft rearmed, and determined to make up for their error, Sub Lieutenant Terry Goddard – an Observer in Swordfish 5K – had not actually been on the earlier attack but, come the evening of 26 May, he surely felt the burden of history in the making on his young shoulders.

“I think we were well aware that Bismarck had to be stopped and we had to stop her,” Terry would recall. “I am not sure that we felt that we were going to sink her but I think when we took off we all had the feeling we certainly were going to damage her…”

Fortunately, that night the Swordfish torpedo-bombers found and attacked Bismarck, with Terry Goddard’s aircraft the last to go in. “The flak is bursting over our head,” recalled Terry, “the small arms fire is pretty well all around us – and hitting us every once in a while – but we get in to drop the torpedo…do a quick turn away. Looking back shortly after the turn I see a large black and white explosion on the Bismarck. It is high and wide. Obviously, it is a torpedo hit. There is no other aircraft anywhere near us and there is no doubt it was the torpedo we had just dropped.”

Swordfish torpedo-bombers from HMS Ark Royal attack Bismarck on the night of 26 May 1941. Artwork by Dennis Andrews.

It isn’t the key hit – that has already been delivered via another Swordfish, in Terry’s view by Ken Pattisson’s Swordfish 2A – with Bismarck’s steering so badly damaged she stands no chance of reaching safety in Brest on the French Atlantic coast.

The British naval aviators could feel well satisfied. There was now a solid chance for the Royal Navy to avenge the loss of 1,415 shipmates killed just over two days earlier when Bismarck’s gunnery blew apart battlecruiser Hood.

For many of the men in warships scattered across the Atlantic – all heading towards a showdown with the Nazi high sea raider – it was a deeply personal mission. Many of them had known sailors and marines serving in Hood. A good few of them had at one time even served in Hood themselves. Now, crippled following a torpedo hit courtesy of the Ark Royal strike, the Bismarck was a mortally wounded beast that needed to be finished off.

The battleships of the Home Fleet – HMS King George V and HMS Rodney – were still steaming hard for the scene and, along with the RN’s heavy cruisers, would make their attack in the morning, secure in the knowledge that their quarry could not get away before then.

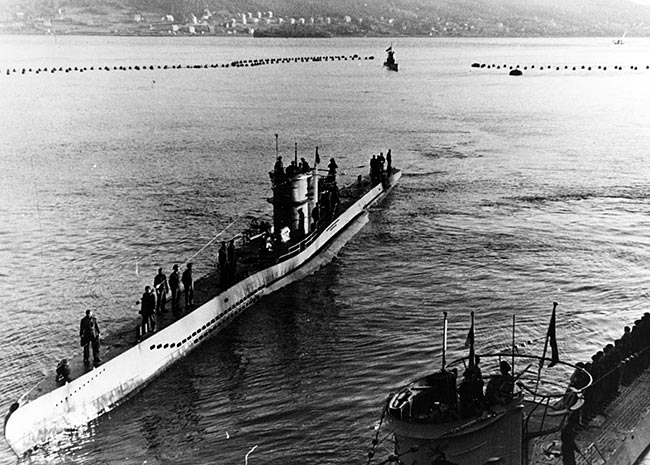

HMS Cossack, which led the 4th Destroyer Flotilla during the Bismarck Action. Photo: Courtesy of the HMS Cossack Association.

In the meantime, Capt Vian’s ships would harass and seek to further damage the German giant, with HMS Cossack leading the way for the destroyers’ attacks on the night of May 26. Ken Robinson recalled: “We went in head to sea and fired a spread of torpedoes. At the time, we thought one of them had hit.”

Having tried her luck, Cossack did not hang around, Ken remembering that his ship “turned and with the sea up our stern, sped away at what seemed to be the fastest we ever went, the sea throwing us all over the place.” German heavy shells plunged in around her, their approach seen on the destroyer’s radar but the Cossack got away without being obliterated.