Long Voyage Of ‘Puny Boats’ To Becoming The Mightiest Vessels Of War Ever Seen (Or Rather Unseen)

With this year seeing the 100th anniversary of the end of WW1, in which submarines played a major role, across a series of four blogs Iain Ballantyne looks at the epic story of submarine warfare. As told in his latest book ‘The Deadly Trade: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’, the boats and their crews have progressed from originally being viewed with contempt to inspiring awe and terror. In part one, Iain takes us from early times in submarine warfare to the dawn of the 20th Century and the power of submarines today.

There can be no doubt the submarine in its various forms is a powerful weapon of deterrence and a means to mercilessly wage war or exert control in both coastal waters and the open ocean.

Today nuclear-powered submarines are just about the most complex and costly warships in existence. Creating and operating them is the mark of a Tier 1 nation (as even UK Prime Minister Theresa May might understand).

On the cutting edge of modern submarine warfare: The US Navy attack submarine USS John Warner, which in April 2018 launched cruise missiles to destroy Assad regime chemical warfare facilities in Syria. Photo: NATO.

Armed with nuclear weapons, submarines, such as the UK’s current and future Trident missile boats, possess the ability to destroy millions of lives by potentially inflicting world-ending devastation – they threaten a level of destruction that is beyond our imaginations. It is impossible to conceive anyone would ever unleash such terrible power, but while they exist the risk is always there.

For both sides in the debate on renewing the UK’s Trident deterrent, the answer seems to be simple…the deterrent preserves peace or we are a missile launch away from extinction…Renew it, or get rid of it. The reality is a lot more nuanced than that – even for some who back its renewal the whole issue is imbued with ambivalence – reflecting attitudes towards the application of submarines in wars down the ages.

Both sides of the argument have merit and any sane person would surely wish to have multilateral nuclear disarmament, which hopefully will happen sometime within the next few decades – in fact, the sooner the better.

Yet, in the short-term, is the Continuous-at-Sea Deterrent (CASD) in a submarine the best means to show rogues states and bullyboy would-be superpowers you won’t be pushed around? Does it still prevent an outbreak of major conventional warfare that may costs millions of lives? Possibly it does both and remains a so-called weapon for peace, preventing bad situations from getting even worse.

For, thanks to great power rivalry, today there are several struggles for dominance on land and at sea underway simultaneously. From the Arctic to the Black Sea, from the eastern Mediterranean into Arabia and over the South China Sea and Korean Peninsula war clouds are gathering, or – in some places – have already given way to fire and thunder.

Aside from the rivalry between the great powers underpinned – and overshadowed – by vessels armed with nuclear missiles, in the past few years submarines armed with conventional weapons have been at the forefront of simmering – and sometimes white hot – confrontations between East and West.

Poor torn-apart Syria has more than once been bombarded with cruise missiles launched by Russian conventionally powered submarines and this year also by a nuclear-powered American submarine. Just a few years earlier British and American submarines launched dozens of cruise missiles to help pull down the Gaddafi regime in Syria and even to try and assassinate the dictator himself.

The reach and power now achieved by submarines – to potentially end all life on the planet with nuclear tipped weapons, or seek to change the course of history up to a 1,000 miles inland via cruise missiles – has been a long time coming and was completely unimaginable even a century ago.

In fact the idea of a combat vessel that could remain invisible under the sea until it struck with utmost devastation taunted the imagination of artists, scientists and inventors for centuries before it ever became a practical reality.

In the late 14th Century no less than Leonardo da Vinci made sketches for what he called ‘a ship to sink another ship’. In England during the 16th Century retired naval gunner William Bourne and his former captain William Monson separately created designs for a submersible and an underwater cannon, though neither man sought to make them real.

The challenges involved in creating a viable submarine were considerable: the inventors had to devise a means to dive the vessel, then achieve neutral buoyancy under the waves so it could maintain depth and move up and down (plus also horizontally) at will. A means of propulsion was required, a system of navigation, all while somehow sustaining the lives of the crew and fitting it with a workable weapon. Some died in the attempt but others achieved incremental progress.

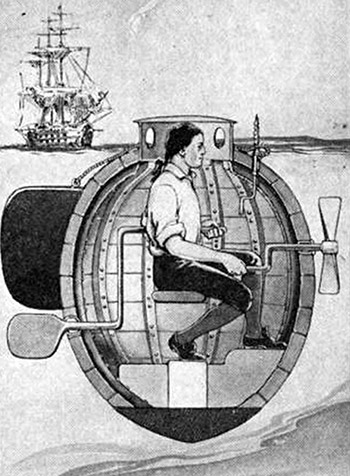

A depiction of Bushnell’s Turtle and with would-be British target in the background.

Image: Public domain.

What really boosted efforts by various people was a desire to destroy the most powerful maritime force on the surface of the ocean – the Royal Navy – with putative diving machines seeking to provide equalisation for those who found their ambitions thwarted by the British.

Among them, in the late 1770s, was the American colonial rebel David Bushnell with his Turtle, reputedly the first fighting submersible. Propelled and manoeuvred by the pilot’s muscle power, the Turtle was a failure when put to the test off New York against a British warship, its attachable mine failing to gain purchase on the hull of the 64-gun Eagle.

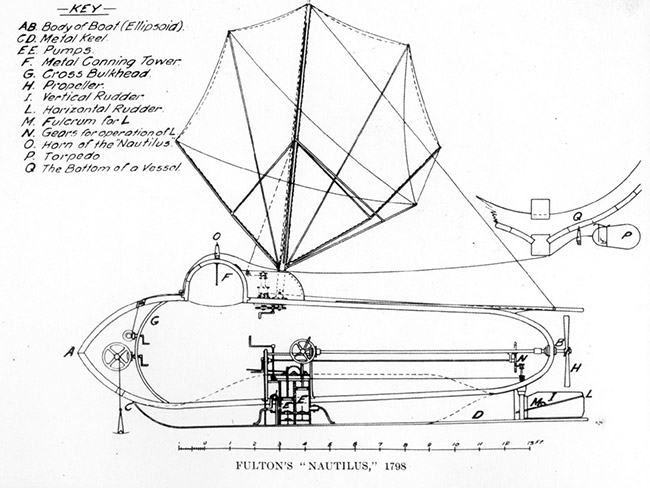

In the early 1800s Robert Fulton, another American, offered the wind and muscle-powered Nautilus to France, aiming to assist its struggle against British naval hegemony. Napoleon ultimately shunned the proposal, thinking Fulton a con artist, so he took his talents to Britain and offered to help destroy the French invasion fleet being assembled to conquer the troublesome English. Fulton fared no better in England – where the top admirals were less than enthusiastic about his proposals – than he had across the Channel and so went home in a huff.

Robert Fulton’s plunging boat Nautilus, built in France but destroyed by Fulton himself to prevent the host nation for exploiting it without his permission. Image: US NHHC.

Later on in the 19th Century the Bavarian artillery soldier Wilhelm Bauer and one-time English clergyman George Garrett were among those who took a tilt at building a proper submersible war vessel.

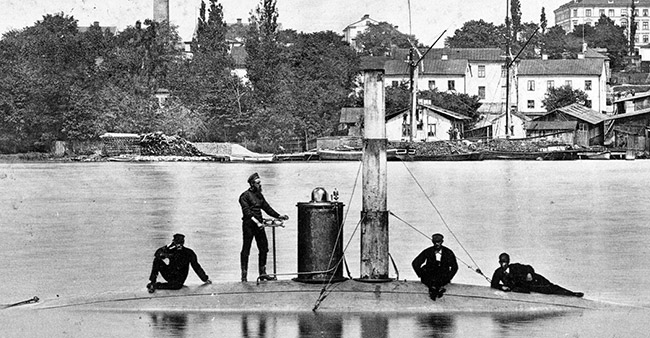

British submarine pioneer George Garrett (with bushy beard) at the helm of a Nordenfelt submarine boat in the Baltic during the 1880s. Photo: US NHHC.

Bauer’s large metal box with a snout, the Fire Diver, relied on two musclemen using a treadmill for propulsion and the air it enclosed to make sure its occupants did not suffocate. The Fire Diver’s means of attack was a pair of mechanical hands fixed to the outside, which were meant to attach an explosive charge to the would-be target vessel. Unfortunately, it got stuck in the mud on the bottom of Kiel harbour, with Bauer and his assistants only narrowly avoiding death, making the world’s first successful escape from a submersible craft.

Bauer became a wanderer, working in England with Isambard Kingdom Brunel on the Great Eastern steamship at the time of the Crimean War, but fell out with his English hosts. He headed for Russia and offered a new submersible attack craft called Sea Devil to the Tsar, whom he tried to charm by sending musicians under the waves in it to serenade him. Russian admirals were less impressed – they were offended by its sheer cheek in seeking to sneakily sink surface ships – and allegedly conspired to sabotage Sea Devil, which ended up coming to grief on the bottom of a basin at Kronstadt naval base.

Some 30 years later George Garrett – in addition to being a former Manchester curate, a one-time school headmaster in strife-torn Ireland where he invented razor-edged mortarboards for his teachers to wield in order to protect pupils – worked with the Swedish engineer and arms manufacturer Thorsten Nordefeldt.

With the notorious Basil Zaharoff as their salesman they endeavoured to sell steam-powered submarines to various countries. Garrett’s boats didn’t work very well, though one sold to the Ottomans distinguished itself by becoming the first ever submersible to fire a self-propelled torpedo while dived. Garrett’s career as a submarine inventor came to a shuddering halt when a large vessel sold to the Russians ran aground on the delivery voyage.

Steam wasn’t necessarily a bad idea – after all nuclear-powered submarines of today are steam powered – but Garrett’s reach was far in excess of technological practicality of his era, and he exhibited poor attention to the detail of operational utility. His boats need a whole day cruising on the surface to build up enough steam to manage only three knots when dived – with erratic depth keeping – and then could stay (more or less) submerged only for a few hours. Also, the threat of being broiled alive was a distinct danger for Garrett or anyone else daring to sail his creations under the sea.

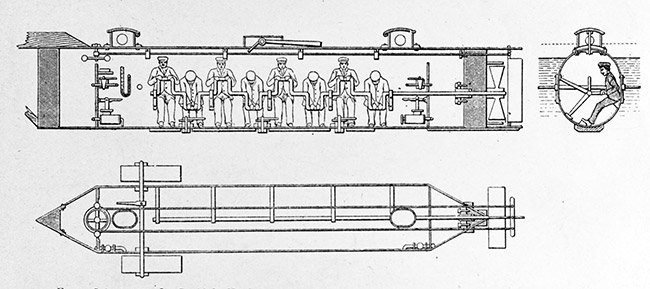

Some years earlier the deaths of three crews in pursuit of an effective undersea war vessel did score a notable achievement. For the early submarine inventors included Confederate rebels who during the American Civil War of the 1860s created the H.L. Hunley, which was again man-powered and had several fatal mishaps while in development, but would make history.

The H.L. Hunley actually managed to use a spar torpedo to sink the Federal Navy warship Housatonic, the first vessel ever claimed in war by an underwater craft. The Hunley may have made history but sank herself in the process – sustaining fatal damage to her watertight integrity thanks to the explosion – and carried her last crew to a watery grave.

A cutaway drawing of the H. L. Hunley with crew ready to propel the craft through the water.

Image: US NHHC.

By the end of the 19th Century, however, there were signs that, finally, someone might yet produce a workable undersea war machine, which is where we will pick up the story in the next part of this short series.

This article is a revised and expanded version of part of an article that was first published in ‘Scuttlebutt: the magazine of the National Museum of the Royal Navy (Portsmouth) HMS Victory and the Friends’

For much more on these incredible true-life tales, read ‘The Deadly Trade: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (752 pages, hardback £25.00/eBook £12.99) which is available via Amazon or Waterstones and other retailers and shops.

For much more on these incredible true-life tales, read ‘The Deadly Trade: The Complete History of Submarine Warfare from Archimedes to the Present’, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (752 pages, hardback £25.00/eBook £12.99) which is available via Amazon or Waterstones and other retailers and shops.

Comments

Comments are closed.